Download Paper Back to Research Paper Series

| Suggested Citation: Brunssen, Pavel and Andrei Markovits. 2024. "From Chants to Change: German Soccer's Unique Response to Antisemitism Post-October 7." ISCA Research Paper 2024-3. |

Download Paper Back to Research Paper Series

| Suggested Citation: Brunssen, Pavel and Andrei Markovits. 2024. "From Chants to Change: German Soccer's Unique Response to Antisemitism Post-October 7." ISCA Research Paper 2024-3. |

by Pavel Brunssen and Andrei Markovits

October 2024

In August 2023, the German soccer club TuS Makkabi Berlin celebrated a milestone that was observed worldwide: for the first time since Jewish soccer clubs were banned in Nazi Germany, a Jewish sports team partici- pated in the main national German cup tournament. Although the Ber- lin Makkabi team lost to Bundesliga team VfL Wolfsburg, many saw this match as a symbol of the successful reconstruction of Jewish life in Ger- many after 1945. Despite the Makkabi sports movement’s success since its post-Nazi revival in 1965, its athletes have been continually subjected to antisemitic chants embodying a serious level of open discrimination, and, on occasion, physical aggression and violence.[1]

A few weeks later, and immediately after the antisemitic massacre by Hamas in Israel on October 7th, 2023, Jewish sport in Germany announced it would pause all match play considering the fluid secu- rity situation. Shortly after the festive atmosphere that surrounded the Makkabi cup game, the German public was reminded that the reestab- lishment of Jewish life in Germany after the Holocaust has always been confronted with antisemitism. For decades, the latent antisemitism present on German sports fields has frequently become visibly manifest when violence in Israel/Palestine dominates the global news.

The pogrom of October 7 led to a pervasive feeling of intimidation among Jews and Jewish institutions in Germany—including in sport. However, shortly after the announcement that all play would be sus- pended, Makkabi Berlin declared: “As a multicultural team that also brings together Muslims and Jews, we absolutely want to continue play- ing and not let ourselves be defeated.”[2] The Makkabi teams throughout the country continued to play with increased security—despite or per- haps because of the threat at hand. The reactions of the Makkabi sport movement unambiguously show how Jews in Germany are aware of permanent antisemitic background noise. Yet they also show that sport offers an important platform for Jewish self-assertion and for taking a stand against discrimination.

After October 7 and during the Israel-Gaza war, European cultural organizations, including those in the realm of soccer, increasingly raised their voices against the Israeli attacks on Gaza while largely remaining silent about Hamas and its assaults on Israel. For instance, supporters of Celtic Glasgow displayed a banner in the stadium immediately after October 7 declaring “Free Palestine. Victory to the Resistance!” To some soccer fans in Europe, the enmity towards Israel manifested itself on October 7 and subsequent days celebrating the Hamas attack well before Israel’s incursion into Gaza. In Germany, however, the soccer community exhibited a completely different perspective: fans displayed banners such as “Bring them home now” in solidarity with the hostages, clubs published similar statements, and representatives of the German league even travelled to Israel to visit the sites of the massacre and meet survivors (see figure 1). German soccer is thus a diverse and ambiguous field for Jews: while antisemitism persists, soccer also offers a space for belonging and solidarity. In the following, we analyze why soccer has offered a specific opportunity structure for adversity and hatred before providing a brief overview of different forms of antisemitism in German soccer. We will then conclude by discussing a significant and curious contrast to the situation witnessed in most European countries and to antisemitism’s persistent and potent presence in German soccer: This sport, Germany’s most popular by any measure, has come to provide a space for Jewish participation that offers a firm solidarity toward Jews and Israel amidst the local and global rise in antisemitism after October 7.

Soccer, with its dual structure in which two teams compete while also representing their respective cities and regions, provides an easily acces- sible and effective outlet for aggression. This binary is further reinforced by the stadium architecture, which is divided into two coaching zones, two halves of the pitch, two warm-up zones, as well as home and visiting fan areas. The pioneering Dutch sociologist Johan Huizinga’s analysis of sport, which he deems fundamentally agonistic and focused on winning, explains why hatred and aggression towards the opponent thrive in this arena.[3] The high value placed on winning encourages a willingness to use any means necessary to achieve the desired victory and avoid a dreaded defeat.

To most fans, fairness in sports matters only when the stakes are relatively low and their emotional involvement is minimal. The more emotional the fans’ investment, the higher the risk of their deviance and manipulation in the pursuit of a single goal: winning. Selfishness is an essential part of being a fan, leading many to brag, insult, and some- times discriminate. The pursuit of victory is the driving force in sport. All means justify the sole end that counts to the devoted fans: winning! Soccer supporters do not believe in fair distribution and their desire to win knows no bounds. The only comparable pleasure for true sports fans is schadenfreude i.e. reveling in the hated rival’s losses. In some ways, the characteristics exhibited and demanded by “true” fans bear similarities to fascist traits: pure emotionality, unrelenting hatred of enemies, con- tempt for weakness, ridicule of opponents, insatiable desire for constant victory, and little willingness to share.[4]

Soccer constitutes Germany’s “hegemonic sports culture.” Such a culture primarily encompasses the act of following (i.e. the consum- ing of sport as a spectacle) and only secondarily the aspect of doing (i.e. the performing, the production of sport as a physical activity).[5] A hege- monic sports culture contains everything that people read, discuss, and keep in their memory. In other words, it is something that is ubiquitous to the every-day life of fans. Although soccer is omnipresent in the pub- lic sphere, it also offers anonymity: in the crowd, one can be anonymous and public at the same time. In this context, it becomes permissible, often even commendable, to say things or behave in a manner that are frowned upon elsewhere as intolerable expressions of negativity and hatred.

A close connection to soccer clubs is a significant marker of a person’s very identity as clubs are perceived as an extension of the self. They are seen as “traditional” and “locally rooted.” In soccer, a club represents a city, and its players “fight” for the pride of an entire region. Players from the youth sections of the clubs are celebrated as “home-grown,” while others are denigrated as “soulless mercenaries.” Within the framework of antisemitism, the object of hatred constitutes the opposite to local tradition: Jews are global, cosmopolitan, modern; in other words, every- thing that an authentic soccer club is not supposed to be. The norms and values of hegemonic soccer provide a field in which antisemitism can exist and even flourish in a contemporary liberal democracy.

The mixture of tradition and local patriotism leads to a tendency to reject everything “modern” and “global.” This can also lead to soccer fan- dom’s link with antisemitic and anti-American sentiments. An example: On 11 May 2002, several thousand fans of various German clubs dem- onstrated together in Berlin against the “rampant commercialization of soccer.” From a loudspeaker van, one fan summed up the idea of tradi- tional soccer in a song as follows:

What would soccer be without atmosphere? What would soccer be without fans? It would be like schnitzel without chips, it would be like sausages without mus- tard! Who needs cheerleaders and popcorn? There’s no movie theater and no football here! We just want pure soccer, because we, we are the fans![6]

The fans not only demand participation and a say in their team’s fate and the sport’s very existence, but also evoke images of “pure” soccer: the (good) tradition of soccer, embodied by the traditional and beloved German snack, “sausages with mustard,” is contrasted with the commer- cial, global, and Americanized sport of football, which is represented by cheerleaders and popcorn.

Since the 1990s, the gap between very wealthy and less endowed clubs has widened, leading to increasingly fewer surprises in the rank- ings at the end of a season with, unsurprisingly, the rich clubs enjoying almost constant success. Although titles and victories remain impor- tant, the growing supremacy of some clubs has also changed the iden- tities of many fans: while the clubs that have most benefited from the “gentrification” of soccer in recent decades are most successful, many supporters are increasingly defining their fanhood in terms of other val- ues. Their definition of authenticity in soccer is less linked to champion- ships and instead is increasingly based on preferences such as being an underdog, having a long and rooted history, and, most important, not being commercial—characteristics that are denied to Jews or Ameri- cans. Although almost all of today’s team sports, including soccer, are quintessential capitalist entities and thrive in capitalist conditions of production, the true authenticity of soccer to its most ardent fans mani- fests itself in supposedly pre-capitalist, even anti-capitalist, formations such as family, friendship, pubs and clubs. Although money is the be- all and end-all of professional sport, it simultaneously diminishes its authenticity and is therefore frowned upon by real fans. Capitalism is considered a necessary evil that fans tacitly abide, but they never accept its presence as honorable or authentic. In addition to rootedness and tradition, toughness and masculinity are considered particularly authentic in hegemonic sports, thus adding a further layer for potential hostilities and violence.

Soccer was and still is essentially about winning. Titles, triumphs, and victories over the biggest rivals are the events that feature prominently in a fanbase’s collective memory. But the current situation reveals an interesting and rather novel contradiction: whereas winning has become a greater priority than ever before in the sport itself, the salience of tradi- tion and belonging have become more important to the fans. The club’s being supersedes its players’ achievements on the field.

Antisemitism in soccer is also a form of emotional discharge result- ing from the tension of striving for success and authenticity. Antisemitic behavior targets players, associations, and clubs that may have nothing to do with Jews but are perceived as representing capitalism which, of course, is associated with Jews. This dynamic is particularly evident in an emotionally invested area such as men’s soccer with its being virtu- ally unknown in the women’s game.[7] Tribal masculine traits such as honor and pride also include derision and rejection, which often evoke antisemitism. Soccer has a dual function: it offers a sense of belonging, including for Jews. However, through this belonging, which is charac- terized by localism, it also offers the potential for exclusion of minori- ties: “Us and the others.” The combination of tribalism driven by raw emotions creates an arena that is difficult to navigate for Jews and other minorities and in which different forms of antisemitism persist.

Antisemitism continues to exist in and around German soccer in many different forms: chants, banners, street art, social media posts, threats and violence against various individuals, groups, and institutions.[8] In this context, Pavel Brunssen has proposed a typology that identifies the various forms of antisemitism in soccer: 1. far-right antisemitism, 2. classical antisemitism, 3. secondary antisemitism, 4. antisemitism against Makkabi clubs, 5. antisemitic ressentiment against RB Leipzig.[9] Despite an increasing social commitment by fans, clubs, and associations in recent decades to fight this scourge, antisemitism remains a prevalent phenomenon in Germany’s soccer stadiums.

Far-right antisemitism: Basically, this is a form of antisemitism that has openly and proudly employed Nazi terminology and phrases. Fan groups have called themselves “Zyklon B,” so named after the gas used by the Nazis to exterminate Jews during the Holocaust; or “Standarte 88,” denoting an SS division stationed in Bremen as well as the code “88,” symbolizing the eighth letter of the alphabet “H” , hence, “Heil Hitler.” Although not all hooligans have been part of the far-right, many of them have included neo-Nazis who engaged in fan chants like the “U-Bahn- Lied” (“Subway/Metro Song”), in which fans sang about the construc- tion of a subway line from the opposing club’s stadium to Auschwitz. Equally striking was the chant “Germans defend yourselves—don’t go to St. Pauli!”, which echoed the antisemitic slogans of the Nazis invok- ing German “self-defense” against Jews and Jewish businesses, thus neg- atively associating with this antisemitic trope the Hamburg-based club St. Pauli, arguably Germany’s most socially progressive and inclusive soccer club. The association of hooligans with German soccer stadiums in the 1980s intensified extremist right-wing antisemitism in the sport. Even though there has been a decline in this form of antisemitism since the 1980s, and the “U-Bahn-Lied” and similar far-right chants are rarely heard today, antisemitism itself has not disappeared and continues its existence in the far-right milieu and beyond. Far-right antisemitism remains present in soccer stadiums, manifesting itself, for example, in the use of images of Anne Frank to defame opponents.10 Although less frequent today, far-right antisemitism remains the focus of the authori- ties and the media. Alas, far-right antisemitism is not the only existing form of this hatred present in German soccer stadia; nor are neo-Nazis its sole purveyors.

We categorize classical antisemitism in soccer as the open denigration of and discrimination against Jews based on negative stereotypes which, however, eschew openly Nazi phrases and images. But these expressions explicitly use the term “Jew” in accusatory terms and employ often con- ventional antisemitic stereotypes. This includes spreading conspiracy theories about the powerful, which, in soccer’s case, includes supposedly “corrupt” referees, and, of course, the ubiquitous canard that the media are dominated by Jewish interests. Classical antisemitism goes beyond the boundaries of neo-Nazi groups; it has permeated the sport right up to the boardrooms of the sports associations. The Deutscher Fussball Bund (DFB), the country’s all-powerful national soccer federation lording over the game’s every facet in the country, has issued comments tinged with antisemitism. When canceling an international match in Berlin’s Olympic Stadium on April 20, 1994, Adolf Hitler’s birthday, the then DFB media director Wolfgang Niersbach publicly claimed that April 20 was immaterial to the DFB and only was an issue to voices whipped up by American media, 80 percent of which was controlled by Jews who closely follow events in Germany, wishing the country and its people nothing but ill.[11] By Niersbach’s logic, the cancellation of the interna- tional match was, therefore, the result of a Jewish conspiracy emanating from a Jewish-influenced America.

Post-Nazi or “secondary” antisemitism exhibits characteristics that one can best describe as “defensive,” according to which the perpetrator becomes the victim, as in the Jews relentlessly haunting the Germans with their Holocaust to deny them patriotic excitement and national pride. The same pattern also pertains to Israel whose very existence, in this mindset, provides a burden for Germans and Germany. Secondary antisemitism was expressed, for example, by fan groups in the 1980s and 1990s who desecrated Jewish cemeteries. More recently, Israel-related antisemitism emerged in verbal attacks toward former FC Kaiserslaut- ern player Itay Shechter, an Israeli who was labeled by some of the club’s supporters as a “Dirty Jew!” and greeted with the Hitler salute. In an Under 19 youth match between Maccabi Netanya and a Lütgendort- mund city team, antisemitic chants such as “Jews out of Palestine. Never again Israel!”, perverting the “Nie Wieder” - “Never Again” slogan associ- ated with Holocaust remembrance, emerged prominently. Jews are often vilified for even raising the issue of antisemitism, which allegedly vic- timizes Germans and is regarded a much more aggressive act than the antisemitic deeds themselves.

While far-right, standard, classical antisemitism as well as secondary antisemitism exist independently of the actual or assumed presence of Jews, there is also a strain of antisemitism that is directly and openly targeted at Jewish people and institutions, which Brunssen categorizes as antisemitism directed against Makkabi clubs. The Makkabi sports clubs, which in the first decades of their (re-)founding in 1965 not only served as an athletic outlet for Jews but also made the Jewish community in Germany more visible, are still the focus of antisemitic attacks today. Merely wearing a Makkabi jersey can be enough to become a target of antisemitism. A Makkabi member recalls an incident during a match when an opponent, hands raised, shouted, “You are a filthy people— freedom for Palestine.”[12] This specific, targeted antisemitism illustrates the challenges that Makkabi clubs face as they strive for participation and sportsmanship.[13]

The violent attacks against Makkabi go beyond verbal insults and include visual assaults, such as the painting of swastikas on sports facili- ties, as well as threats and physical attacks. The Makkabi clubs are also confronted with secondary antisemitism: for example, they are accused of being “hypersensitive” when they point out antisemitic incidents and alert the public to various incidents that exploit the Holocaust.

A further and prevalent dimension of antisemitism in soccer exists in the hatred against the club RB Leipzig. This club is often the scapegoat for a perceived termination of allegedly organic traditions, home-grown fan culture, and genuine emotions. RB Leipzig has been subjected to hostil- ity since it was founded in 2009, with more than half of German soccer’s so called ultra groups, the fans who normally support their team at every match, boycotting RB Leipzig’s home field, the “Red Bull Arena.” The criticism of the club is not limited to sporting aspects but also includes the invoking of the dichotomous patterns of tradition versus modernity, local versus global, and authentic versus artificial, in all of which the lat- ter term in the pair—i.e. “modernity,” “global,” and “artificial”—is nega- tively constructed as being inauthentic and has historically and in many other cases directly targeted Jews and Jewish organizations.

The unique dynamic of this ressentiment against RB Leipzig lies in the fact that it functions as “antisemitism without Jews” and “antisemitism without antisemites.” RB Leipzig is a symbol for general capitalist con- ditions in professional soccer, which fans personify, reject, and attack in the form of a specific actor and a specific team. The antisemitic tropes do not manifest themselves explicitly in the critics’ intent but rather in the deep structures of how this hostility is communicated. Metaphors of rats and locusts—it hardly could get more stereotypically antisemitic than that—as well as the rejection of the supposedly global, modern, and inauthentic are virulent in the construction of this bogeyman. Anti- semitism exists here as a worldview in which the “good and upstanding club rooted in national sport” is contrasted with the “evil and homeless plastic club.” Because RB Leipzig is never addressed as “Jewish” in any explicit way, the underlying antisemitic trope of hatred and exclusion is readily available even to fans who deem themselves liberal and distant from any traditions of antisemitism.

The rejection of RB Leipzig also serves to maintain the overwhelm- ingly masculine prevalence of fan culture: tradition, authenticity, and toughness are associated with masculinity, while “fair weather fans,” “commercialization,” and “softness” are associated with femininity. The antisemitically charged bogeyman is linked to the defense of a tradi- tional and supposedly proletarian image of masculinity in soccer, which sees RB Leipzig as a symbol of the supposed loss of these values. While open antisemitic expressions have been largely banned from the stadi- ums, soccer’s function as a field for antisemitic ressentiment, adversity, and hatred remains intact.[14]

Considering the pervasiveness of antisemitism and its root causes in German soccer, the responses of solidarity with Israel and Jews in Ger- many after the October 7 terror attack has highlighted surprising and significant changes in the topography of German soccer.

After it became clear that Hersh, an Israeli soccer supporter of the Ger- man team Werder Bremen, was among the hostages taken to Gaza on October 7, the club and its supporters launched a fervent campaign with the rallying cry, “Let Hersh Free!” For months, this call for his release echoed from the stadium terraces around the globe. But in early September 2024, the devastating news of Hersh’s death in Gaza sent shockwaves through the club. In a heartfelt tribute, Werder Bre- men replaced the flag in front of their stadium with one that read “Rest in Peace, Hersh!” Fans gathered to lay flowers, candles, and personal mementos, mourning the loss of their cherished friend and paying their final respects (see figures 2–4). During the club’s next game, the fans displayed a large flag: “Hersh Forever!” (see figure 5).

Jews and Israelis have faced a significant rise in antisemitic incidents and hostility following the October 7, 2023 terror attack. A German institute for monitoring antisemitism, “Recherche- und Informations- stelle Antisemitismus Berlin (RIAS Berlin),” documented almost 1,000 antisemitic incidents between October 7 and November 9, 2023.[15] The report concluded that October 7 has created “a new reality for many Jews” in Germany, who continue to encounter manifold forms of antisemitism from acquaintances in their neighborhoods to complete strangers, in their workplaces or at universities. Curiously, while 387 of the reported incidents occurred in the streets, only 3 happened at stadiums or sport facilities.16 Given the long tradition of and the continuing opportu- nity structure for antisemitism in professional men’s soccer, one would expect at least a similar rise of anti-Jewish animosity in and around Ger- many’s favorite sport that has occurred in virtually all aspects of Ger- man society. Yet, to our great surprise, German soccer fans and clubs did not express hostility against Israelis but instead showed an impressive range of solidarity with the victims and hostages of October 7.

The support for Israel was not unanimous. Controversy arose when German Bundesliga players made social media posts perceived as glorifying the October 7 attack on Israel. Bayern Munich’s Noussair Mazraoui and a player from Mainz 05 faced public criticism from Makkabi and the Central Council of Jews in Germany, among others. The debate centered on the balance between personal expression and professional responsibility, as well as antisemitism and “Israelkritik” (criticism of Israel). In response, Mazraoui held discussions with FC Bayern leadership and Munich's Jewish community, while Mainz 05 terminated its player’s contract.

Soccer clubs like Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund publicly and forcefully condemned antisemitism. They also organized tributes to the Israeli victims and hostages, including moments of silence and special matchday events. Borussia Dortmund repeatedly invited survivors and relatives of victims from Israel to their games. Hertha BSC invited 11 children who survived that horrible day to their German cup game against Hamburg SV, from whom the kids received personalized jerseys. In May 2024, the Deutsche Fußball Liga (DFL) organized a trip to Israel for Bundesliga and 2. Bundesliga staff involved in fan support, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), and communications. The group partici- pated in the Holocaust Remembrance Day event at Yad Vashem and met eyewitnesses of the Hamas attacks as well as relatives of hostages (see figure 6). This unexpected solidarity can be attributed to the efforts of fan organizations and clubs to educate against discrimination. Decades of fan activism and more recently also a proactive stance taken by Ger- man soccer authorities has fostered a particular environment, showcas- ing the potential for sports to lead by example on societal issues.[17]

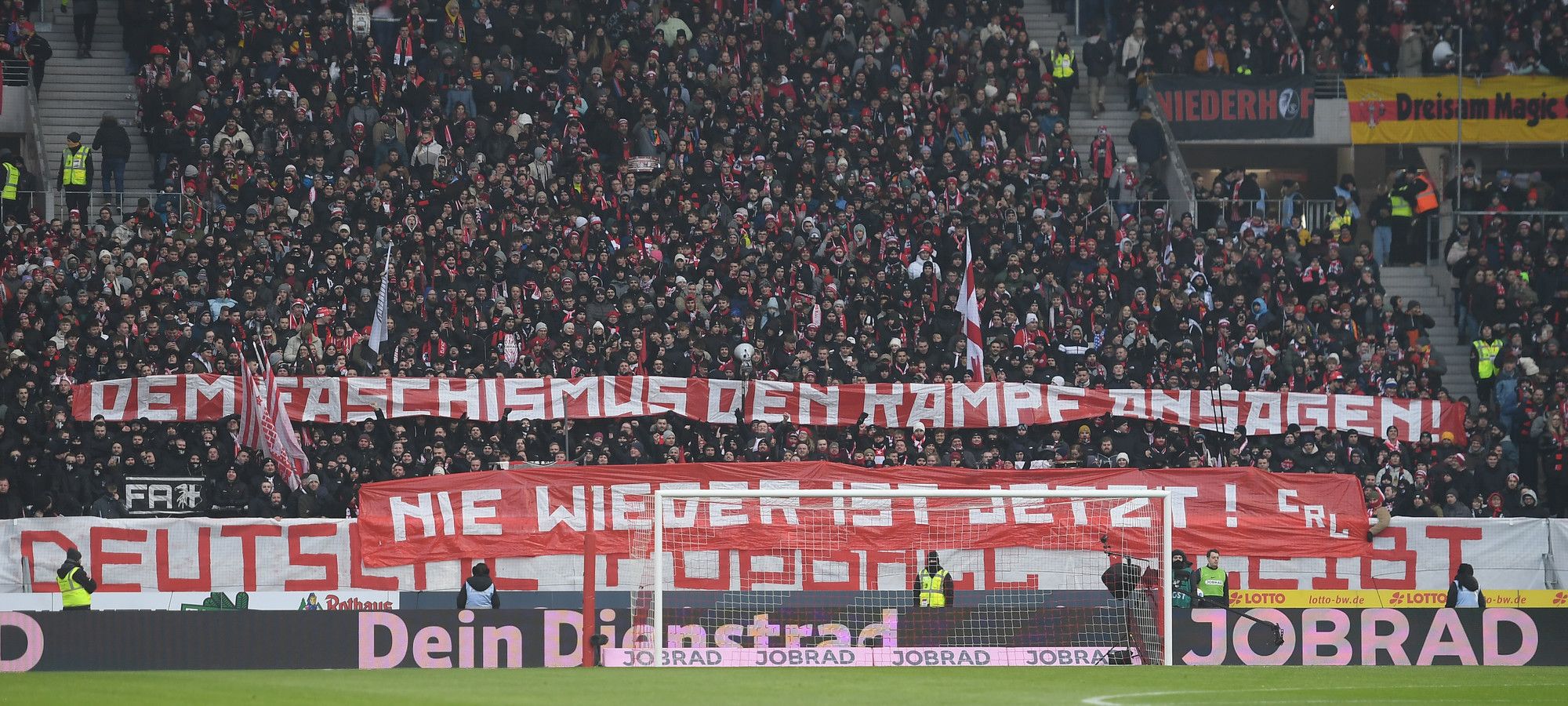

On October 7, only hours after Hamas terrorists had infiltrated Israeli territory, Werder Bremen fan groups displayed hastily produced ban- ners during the club’s evening home game against Hoffenheim display- ing such slogans as “Stand with Israel!” Three days later, the same club published a photo of captive Hersh Goldberg-Polin on its social media accounts, explaining that Hersh, a supporter of Hapoel Jerusalem, last visited a Werder home game in January and now needed immediate medical care.[18] More banners, statements, demonstrations, and a fund- ing campaign followed. One Werder fan group displayed the slogan “always together” in Hebrew alongside heart-shaped cardboards with the names of the Maccabi Haifa supporters who were either murdered or kidnapped. Others displayed banners stating, “Every attack on Jew- ish life is one too many!” (see figure 7) and when it became clear that Maccabi Haifa fan Inbar Haiman was murdered in Hamas captivity in Gaza, Werder fans created a large choreography in her honor. In 2024, the first Werder fan organization was founded in Israel, claiming that the club’s and fans’ actions after October 7 brought the Werder fans in Israel together to finally found an official fan club. The fans of other clubs engaged in similar displays: Supporters of 1. FC Cologne created fan scarves against antisemitism and a fundraising campaign to provide emo- tional support after October 7. Supporters of fourth league club Chemie Leipzig displayed banners demanding “Peace for the people of Israel” and “Free Palestine from Hamas. Stop Terrorism and Fascism. Freedom for all People.” Fans of FC St. Pauli, who have a longstanding friendship with those of Hapoel Tel Aviv, displayed banners such as “Hapoel Mish- paha [family]. Always with you.” Supporters of SC Freiburg responded directly to the rise of antisemitism in German society with banners stat- ing: “Germany 2023: houses are marked (with a Star of David), syna- gogues attacked, people stay at home out of fear. Never again is now! Against all sorts of antisemitism!”. They repeatedly displayed slogans such as “Declare War on Fascism! Never Again is Now!” (see figure 8).

How can we explain that soccer, traditionally a space in which open antisemitism had flourished, has in this very crucial instance become the exact opposite, namely a space in which antisemitism has been largely and surprisingly absent and was outnumbered by expressions of solidar- ity with Israel and an open rejection of antisemitism? To understand this, we must look back to the 1990s. Following decades of hooligans and crisis—in terms of declining financial revenue and stadium atten- dance—soccer became gentrified in the 1990s. From the late 1970s to the mid-1990s, the Hooligan fan culture ruled the stands, bringing not only violence but often also swastika flags, Hitler salutes, as well as anti- semitic and racist chants to German stadia. Alongside the gentrification of the sport, the German authorities issued the national concept “sport and security” (1993), which combined repression against hooliganism, such as video surveillance and stadium bans, with preventive measures in the form of social work with and for fans. Simultaneously, support- ers founded the “Bündnis antifaschistischer Fußballfans” (Network of Antifascist Soccer Supporters), later renamed “Bündnis aktiver Fußball- fans” (Network of Active Soccer Supporters), or “BAFF.” This was a pioneering effort to address the problem of neo-Nazism in soccer, often facing resistance from clubs and authorities. Over time, these efforts laid the groundwork for the ultra-fan movement, which has proven transfor- mative for German soccer’s fan culture—especially in the wake of the October 7, 2023 horrors.

The emergence of the ultra-fan movement, a product of the 1990s transformation of soccer, has since taken the lead in shaping German fan culture. Ultras, known for their passionate displays, banners, and orga- nized chants, have largely supplanted the hooligans of the past, steering the culture in a new direction. While hooliganism has not vanished, the ultras have become the dominant force, and their political leanings are generally more centrist or liberal. In the early 2000s, particularly in the lead-up to the 2006 World Cup in Germany, some ultra groups began to re-politicize the stadium environment, taking a stand against various forms of discrimination. In the 2010s, fans launched nationwide cam- paigns such as “Soccer Fans Against Antisemitism” at Werder Bremen and “Soccer Fans Against Homophobia” at Tennis Borussia Berlin.

In the early 2000s, the ultras’ influence grew, with their creative cho- reographies and organized support becoming the defining features of the stadium experience. Some ultra groups have actively expelled neo- Nazis from their ranks, organized events against discrimination, and initiated efforts to examine and address their clubs’ histories during the Nazi era, leading to numerous publications.

The BAFF initiative brought the reality of antisemitism in German soccer to the forefront with its traveling exhibition, “Tatort Stadion,” in the early 2000s. It also sparked conflict with the DFB, whose lead- ers felt provoked by fans to raise awareness about antisemitism in soc- cer from the very top of the federation. The period between 1998 and 2006 marked a transformative era concerning discrimination in soccer.

In 1998, the brutal beating of French gendarme Daniel Nivel by Ger- man hooligans during the World Cup in France sent shockwaves around European soccer. This incident occurred at a time when the DFB was preparing its bid to host the 2006 World Cup, a bid it was determined not to see undermined by right-wing hooligan violence.

German stadiums underwent significant modernization, incorporat- ing advanced security and surveillance technologies. The police, contro- versially, began building and expanding databases to track fan violence. Concurrently, the DFB commissioned the study “Soccer Under the Swastika—The DFB Between Sport, Politics, and Commerce,” which was published in 2005 yet drew immediate criticism for downplaying the role of German soccer in Nazism.[19] That same year, the DFB established the Julius Hirsch Prize, named after the prominent German Jewish soc- cer player Julius Hirsch, who was murdered in Auschwitz, an award to honor individuals and initiatives promoting tolerance. Moreover, the cultural program for the 2006 World Cup prominently featured themes of diversity and anti-discrimination. This period also witnessed the cre- ation of the DFB’s Department of Social Responsibility, a move that laid the foundation for many of the structures and preventive measures that exist today.

In addition to grassroots movements, major soccer associations like the DFB and DFL, along with several professional clubs, adopted the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism. While the true impact of this adoption is difficult to gauge, it undeniably reflects a broader societal commitment to combating anti- semitism, a stance with which sports organizations are now increas- ingly aligned. This societal shift and the massive institutional changes in response to active interventions in policy on the part of elites unques- tionably influenced the strong reactions within the soccer community following the events of October 7.

A growing number of clubs now participate in the “Never Again” campaign, which, since its foundation in 2004, annually calls for activi- ties in and around stadiums on Holocaust Remembrance Day, January 27.[20] This date marks the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp by the Red Army in 1945. For the 20th anniversary of remembrance day in German football in 2024, the “!Never Again” ini- tiative called for active engagement with the past and a renewed commit- ment to promoting respect, diversity, and democracy in the present. As part of the #everynamecounts project launched by the Arolsen Archives, the initiative mobilized soccer fans as online volunteers to digitize the names and records of victims and survivors of National Socialism, ensuring that their stories remain accessible and preserved for future generations (see figure 9 and 10). Further supporting these efforts are the DFB Cultural Foundation and the DFL’s “Pool for the Promotion of Innovative Fan Culture,” which fund projects promoting civil courage. The regional DFB associations have also established positions dedicated to addressing discrimination and violence. Additionally, the State Work- ing Group of Fan Projects in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) initiated the “Reporting Office for Discrimination in Soccer in NRW” (MeDiF- NRW), providing a formal mechanism for addressing issues of discrimi- nation within the sport.

This landscape of activism and responsibility extends across many clubs, with Borussia Dortmund (BVB) assuming pride of place for its comprehensive, long-term strategy against discrimination. BVB’s approach comprises five pillars: fan work, internal measures, network- ing, public relations, and remembrance politics. The club has developed numerous initiatives, particularly in the realm of remembrance, includ- ing regular educational trips to former Nazi concentration and extermi- nation camps in Poland and the publication of educational materials like “Soccer Players in Focus” in 2021, which explores the diverse biographies of athletes.[21] In March 2022, Borussia Dortmund’s stadium hosted a major conference on combating antisemitism in soccer, organized by the DFL, the Central Council of Jews in Germany, and the World Jewish Congress.

As mentioned earlier, the national concept sport and security, short “NKSS,” focused on both the repression and prevention of deviant fan behavior such as violence or racism. The NKSS also laid the groundwork for the establishment of the already founded fan projects—an organi- zation unique to German soccer featuring the involvement of circa 60 clubs. These fan projects are organizations independent of the clubs and their official fan associations They dedicate themselves to social work with fans, which includes supporting and offering initiatives against discrimination and for commemorating the Holocaust. They highlight work particularly with Jewish club members. Today’s efforts by Werder Bremen’s supporters for Hapoel Jerusalem fan Hersh go back to a trip to Israel that was organized by Werder’s fan project in 2011 and in which some of the club’s ultras participated. Such visits to Israel are not uncom- mon among German fan projects and include visits to Yad Vashem and meetings with Israeli supporters, among many other activities. Along- side these efforts, supporters also engaged in educational tours to memo- rial sites such as Auschwitz—an initiative that led to the foundation of “What Matters,” an organization that works closely with German clubs and soccer authorities as well as the World Jewish Congress hence sym- bolizing the institutionalization of anti-antisemitic solidarity in German soccer.

Soccer provides an infrastructure in which antisemitism can emerge. Based on the dual and agonistic structure of soccer, the “us versus them,” clubs are glorified as local representatives fighting for the pride and honor of their region. The extreme importance of winning is accom- panied by a strong emotional investment on the part of the fans, which can range from boasting and insults to outright discrimination against the opponent on the backs of third parties, e.g. Jews. Due to the increa- sing sporting and financial dominance of just a few clubs, authenticity is becoming ever more important. Being authentic is defined by having local roots, tradition, masculinity, and toughness, while global, modern, and financial aspects are considered inauthentic. This situation creates a structure of opportunity wherein antisemitism emerges as a means of emotionally discharging the tension between the pursuit of success and authenticity. In this context of capitalism and identity, belonging to the soccer collective always remains a revocable affiliation for minorities, the antisemitic background noise always perceptible in calls for local roots and authenticity.

Antisemitism long has been a sizable part of German soccer’s very fabric. This said, what we have witnessed in recent years, and specifically since October 7, 2023, is that institutional changes exacted by elites mat- ter immensely in changing supposedly petrified structures and culture. The German soccer world’s surprising solidarity with the Israeli vic- tims of the pogrom of October 7, so rare in other parts of European cul- tures, including soccer, would never have happened had the reforms and changes described above not occurred over the previous two to three decades. These reforms—initiated by fan groups—did not alleviate the deep-seated hatreds, including antisemitism, that a passionate construct of popular culture based on agonism—like soccer—will always tolerate, perhaps even demand. But as students of antisemitism as well as com- parative sports cultures, we would be remiss not to note these positive developments, especially in a country with Germany’s past. They made a positive difference where none was expected and little to none like them has happened elsewhere, least of all the hallowed halls of America’s elite institutions of post-secondary education in which antisemitism has reached a level of expression and acceptance unimaginable a decade ago.

[1] In this text, “Maccabi” is used to refer to the broader international sports movement, whereas “Makkabi” is employed specifically in the German context. The respective spellings reflect the differences in orthography between these contexts.

[2] Marius Epp, “Nach angekündigter Einstellung wegen Hamas-Terror: Makkabi Berlin setzt Spielbetrieb doch fort,” Frankfurter Rundschau, October 13, 2023, https://www.fr.de/sport/fussball/terror-makkabi-berlin-spielbetrieb-einstellung-fortsetzung-kehrtwende-krieg-israel-hamas-92573422.html.

[3] Huizinga, J. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Reprint. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1980.

[4] Andrei S. Markovits, “What Is It about Association Football—the Arrogantly Self-Appointed ‘Beautiful Game’—That Renders Most (Though Not All) of Its Fan Cultures so Ugly?,” in Football and Discrimination: Antisemitism and Beyond, ed. Pavel Brunssen and Stefanie Schüler-Springorum, Critical Research in Football (Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2021), 199–208.

[5] Andrei S. Markovits and Lars Rensmann, Gaming the World: How Sports Are Reshaping Global Politics and Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 13.

[6] Schnitzel mit Pommes - Fandemo Berlin, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NQy6FxeSEzE.

[7] Andrei S. Markovits, Women in American Soccer and European Football: Different Roads to Shared Glory (Nantucket, Massachusetts: Dickinson-Moses Press, 2023).

[8] Florian Schubert, Antisemitismus im Fussball: Tradition und Tabubruch, Studien zu Ressentiments in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Band 3 (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2019); Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland, ed., Strafraum: die (Un-)Sichtbarkeit von Antisemitismus im Fußball (Berlin: Hentrich and Hentrich, 2023).

[9] Pavel Brunssen, Antisemitismus in Fußball-Fankulturen: Der Fall RB Leipzig (Weinheim: Beltz Juventa, 2021), 38–44.

[10] Fans of Lokomotive Leipzig, for example, used the motif of Anne Frank to symbolically threaten their local rivals Chemie Leipzig with destruction.

[11] Martin Endemann, “Sie bauen U-Bahnen nach Auschwitz: Antisemitismus im deutschen Fußball,” in Tatort Stadion: Rassismus, Antisemitismus und Sexismus im Fussball, ed. Gerd Dembowski and Jürgen Scheidle, Neue kleine Bibliothek 76 (Köln: PapyRossa, 2002), 85.

[12] Lasse Müller, “Zwischen Akzeptanz und Anfeindung: Antisemitismuserfahrungen jüdischer Sportvereine in Deutschland” (Zusammen1, 2021), 35.

[13] Lasse Müller, Jan Haut, and Christopher Heim, “Antisemitism as a Football Specific Problem? The Situation of Jewish Clubs in German Amateur Sport,” International Review for the Sociology of Sport, July 26, 2022, 101269022211140, https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902221114057.

[14] Pavel Brunssen has written extensively on the issue of antisemitism related to RB Leipzig: Brunssen, Antisemitismus in Fußball-Fankulturen: Der Fall RB Leipzig; Pavel Brunssen, “Antisemitic Metaphors in German Soccer Fan Culture Directed at RB Leipzig,” in Football Nation: The Playing Fields of German Culture, History, and Society, ed. Rebeccah Dawson et al., Spektrum: Publications of the German Studies Association 25 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2022), 218–39; Pavel Brunssen, “Antisemitic Ressentiment-Communication Directed at RB Leipzig in German Football Fan Culture: The Third Other,” in Football and Discrimination: Antisemitism and Beyond, ed. Pavel Brunssen and Stefanie Schüler-Springorum, Critical Research in Football (Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2021), 81–94.

[15] Bundesverband RIAS e.V., “Antisemitic Reactions to October 7,” November 27, 2023, https://www.report-antisemitism.de/documents/RIAS_Monitoring_Bericht_30-11-2023_Englisch.pdf.

[16] For a detailed list of antisemitic incidents by locations see: Bundesverband RIAS e.V., 9.

[17] Pavel Brunssen and Robert Claus, “Zwischen Anfeindungen und Bildungsprojekten: Antisemitismus und Gegenstrategien im deutschen Fußball,” in Heulen mit den Wölfen: Der 1. FC Nürnberg und der Ausschluss seiner jüdischen Mitglieder, by Bernd Siegler (Fürth: Starfruit Publications, 2022), 419–36.

[18] SV Werder Bremen [(at)werderbremen], “Hilfe für Hersh Goldberg-Polin! Der junge Israeli und hashtag Werder-Fan wird vermisst. Er war beim Musikfestival im Süden Israels, das von Terroristen überfallen wurde, und wurde vermutlich nach hashtag Gaza verschleppt. Hersh ist verletzt and benötigt dringend medizinische Hilfe . . . (1/2) https://t.co/YF5zWy6vYL,” Tweet, Twitter, October 10, 2023, https://x.com/werderbremen/status/1711755945695428982.

[19] Nils Havemann, Fussball unterm Hakenkreuz: der DFB zwischen Sport, Politik und Kommerz (Frankfurt; New York: Campus, 2005).

[20] Felipe Bertazzo Tobar, Gregory Ramshaw, and Fabian Fritz, “Never Again! Fandom and the Culture of Remembrance in German Football,” Leisure Sciences, August 8, 2024, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2024.2388261.

[21] Arolsen Archives, Football Players in Focus: Educational Materials on Sports, Persecution, and Remembrance., 2021.

Pavel Brunssen is a Research Associate and Alfred Landecker Lecturer at the Research Center on Antigypsyism at Heidelberg University. His scholarly pursuits span antisemitism, antigypsyism, memory cultures, European soccer, and fan cultures. He is the author of Antisemitismus in Fußball-Fankulturen: Der Fall RB Leipzig (Beltz Juventa, 2021) and the co-editor of Football and Discrimination: Antisemitism and Beyond (Routledge, 2021). He earned his PhD in German Studies and a Graduate Certificate in Judaic Studies from the University of Michigan, where he was awarded the prestigious Marshall Weinberg Prize for his dissertation. This manuscript, tentatively titled The Making of ‘Jew Clubs’: Performing Jewishness and Antisemitism in European Football and Fan Cultures, is set to be published by Indiana University Press in 2025.

Andrei S. Markovits is the Karl W. Deutsch Collegiate Professor Emeritus and an Arthur F. Thurnau Professor Emeritus at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He just concluded a fifty- year university teaching career at leading institutions in the United States, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Israel. His work on social democracy, trade unions, new social movements, antisemitism and anti-Americanism in Europe; as well as on comparative sports cultures and human-animal relations appeared in 18 languages in many books, articles and reviews. His latest work is a memoir entitled The Passport as Home: Comfort in Rootlessness (Central European University Press, 2021).