Download PDF Back to Research Paper Series

| Suggested Citation: Goda, Norman JW. 2025. "The Genocide Libel: How the World Has Charged Israel with Genocide." ISCA Research Paper 2025-3. |

Download PDF Back to Research Paper Series

| Suggested Citation: Goda, Norman JW. 2025. "The Genocide Libel: How the World Has Charged Israel with Genocide." ISCA Research Paper 2025-3. |

by Norman JW Goda

February 2025

This essay concerns the post-October 7 accusation of genocide against Israel. Genocide is the crime of crimes. States committing genocide are viewed as permanently illegitimate. By itself a genocide accusation is not antisemitic. During the Cold War, the charge was leveled dozens of times by government officials, legal scholars, and activists against France, Portugal, Nigeria, China, Cambodia, the US, and other states.[1] Since the end of the Cold War, judicial proceedings for genocide have been carried out against officials from former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and elsewhere both in ad hoc tribunals and at the International Criminal Court.[2]

Genocide accusations against Israel are different. First, Israel, unlike other states, has been charged with genocide throughout its existence.[3] The genocide accusation is tied to charges of racism, colonialism, and other accusations leveled against Israel since the 1960s.[4] Second, the speed and fury with which the accusations exploded after the Hamas massacres of October 7, 2023, are unusual in the annals of lawfare.[5] And yet regarding Israel’s 2023 war against Hamas in the Gaza Strip, there has been not only a rush to judgment but an effort to redefine genocide itself so that the constitutive elements of the crime itself are lowered.

The genocide libel also deploys a range of antisemitic tropes. One is the linkage of genocide to violent passages in the Hebrew Bible, a linkage which plays on the theme of Jewish chosenness at the expense of others’ existence and which even claims that God is genocidal. Another is the whitewashing of Hamas’s own genocidal intent in lieu of tropes concerning the outsized Jewish thirst for vengeance in the form of disproportionate response.[6] A third is the coupling of the genocide charge with the deliberate killing of children, images of whom are ubiquitous on NGO, social media, and other platforms that charge Israel with genocide.[7] A fourth is the attribution of special powers to the Israeli government by which it and its supporters have fooled western governments into believing that Israel’s actions are legitimate and that the history of the Israeli- Arab conflict is too complex for snap judgments.[8]

A fifth, and this is what makes the genocide libel particularly dangerous, is the association of all Jews with the crime. Jews worldwide are all in on it, either as Zionist enablers, as dishonest back-room lobbyists, or as community leaders who, we are told, “weaponize” the charge of antisemitism to silence the truth-tellers.[9] Other genocide charges over time have not targeted Hutus living in Belgium or Serbs living in Germany. But the genocide libel, fueled by everything from electoral campaigns to public demonstrations to social media, drives rage against Jews throughout the world.

In North America, Europe, and Australia, antisemitic incidents have been too numerous to count, ranging from physical threats against Jews in New York City, to a pre-planned pogrom in Amsterdam, to synagogue attacks stretching from Montreal to Melbourne.[10] And as the Conseil represéntatif des institutions juives de France [CRIF] noted in a January 2025 report concerning the nearly 1,600 antisemitic acts in France the previous year, “The hammering of the false genocide accusation, and its corollary of accusing Israel’s supporters of being ‘pro-genocide,’ have helped to demonize the image of Jews in France and justify hostile . . . behavior towards them.”[11]

My aim, though, is not to discuss why the genocide charge is antisemitic. Nor is it to point to the numerous instances of mass violence in Syria, Sudan, and elsewhere for which activists can never seem to summon the outrage. Nor is it, here anyway, to dismantle the South African genocide charges against Israel from December 2023 or the subsequent ruling of the International Court of Justice that it is “plausible” that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza. Rather my aim is to discuss some of the history of how the genocide accusation has been leveled at Israel and the Jews. By looking at the history, which began even before the genocide convention was completed, we can begin to deconstruct the charge itself, how it has been used against Israel over time, and the stunningly bad faith behind the genocide accusation.

Tens of thousands of Palestinian civilians have been killed in the most recent war with Hamas. There is a discussion to be engaged on the issue of proportional military responses as set forth (very vaguely) in the 1977 Additional Protocol I to the 1949 Geneva Conventions.[12] Hamas, meanwhile, is an aggressive entity, and its destruction is a legitimate war aim. Choking off strategic imports through blockade is wholly in keeping with how legitimate blockades have been used in modern warfare.[13] And Hamas’s fighters, who hide themselves and their weapons both in and under hospitals, shelters, schools, mosques, and the like, put civilians at risk.

UN resolutions from the 1970s which defined terror groups like the Palestine Liberation Organization as national liberation movements struggling against colonial domination, and which say that such movements do not commit the crime of aggression owing to the nobility of their cause, do little more that legitimize terror.[14] The accusation of genocide in the present case works in reverse. It is political, designed not so much to describe a crime, but to place Israel, its military, its citizens, and its supporters as outside the realm of decency and human values.

The legal scholar Raphael Lemkin developed the term genocide in his book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe (1944). Genocide for Lemkin was much broader than physical extermination. The crime, he said in that book, signifies

. . . a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essen- tial foundations of the life of national groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group.[15]

Lemkin’s concept concerning everything from social institutions to national feelings was too non-specific for jurists, particularly as the Nazi proclivity during World War II was for murdering their enemies rather than destroying their culture. The leading Jewish legal scholar of the day, Hersch Lauterpacht, developed the concept of crimes against humanity, which protected civilians from a variety of specific physical crimes and which entered the corpus of international law with the Nuremberg trials.[16] Though Lemkin was involved with the Nuremberg trials, he had little influence on their course, for though the concept of genocide was mentioned, the tribunal narrowed the concept to planned mass murder.[17] Thus the indictment in the Trial of the Major War Criminals men- tions genocide but defines it as “the extermination of racial and national groups”[18]

In 1946 Lemkin lobbied the United Nations to declare genocide an international crime.[19] For Lemkin, who led the early UN ad hoc discussions, genocide remained a broad concept, including crimes against culture and language. UN officials favored greater precision, and with clear evidence of mens rea—the guilty intent essential to any crime. UN Secretary-General Trygve Lie pointed out that genocide should be limited to “the deliberate destruction of a human group” . . . “otherwise there is a danger of the idea of genocide being expanded indefinitely. . . .”[20] Lie added that war itself was not genocidal. “The infliction of losses,” he said, “even heavy losses, on the civilian population in the course of [war], does not as a rule constitute genocide.”[21] John Reid of New Zealand added in October 1948 that motive was especially critical within the framework of a defensive war. There could be a bombing operation, Reid said, that could destroy part of a group. “If the motives for genocide were not listed in the convention,” Reid noted, “such bombing might be called a crime of genocide; but that would obviously be untrue.”[22]

In the meantime, everyone understood that accusations of genocide could be politicized if the constitutive elements were not clear. Trygve Lie warned that, “if the notion of genocide were excessively wide, the success of the convention . . . would be jeopardized.”[23] Indeed, cynicism was never absent from the discussions. Back in Moscow, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin examined each draft of the convention so that recent episodes of Soviet mass violence, such as mass starvation in Ukraine in the 1930s, could not be criminalized. US officials, meanwhile, worried about the criminalization of racial oppression in the US, while those states holding colonies in Africa and Asia were concerned that colonial violence could also form the basis of genocide accusations.

Regardless, the UN drafters created a definition of genocide, passed by the UN General Assembly on November 9, 1948, that centered on the physical destruction of peoples with potential victim groups defined by ethnicity, race, and religion. The definition is “acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such.” The actual acts begin with “killing members of the group,” and the rest of the definition also concerns physical destruction. The convention thus includes provisions such as the prevention of births within the group, but it consciously omits broader concepts such as cultural genocide.[24]

Meanwhile the element of intent, as with all crimes, is the critical constitutive element in how genocide is defined, even more critical than the number of people within a group that might be killed. The French delegation, for instance, insisted that the convention text use the term meurtre—murder—to define the act of killing, as it unambiguously carries the element of intent. Meurtre is the term used in the official French text of the Genocide Convention. The official English language text uses the broader term killing, preferred by the US delegation, the American reasoning being that so long as intent was in the text defining genocide, the killing would have to be intended.[25] Either way, the Genocide Convention is explicit in defining genocide as “acts committed with the intent to destroy [a group] in whole or in part ”

It is noteworthy that UN deliberations on the Genocide Convention coincided with the birth of Israel. The UN struggled to maintain peace in Palestine in the waning months of the British mandate, and it also tried to forge a peaceful solution to the problem of two peoples claiming the same land. UN General Assembly Resolution 181 of November 29, 1947 recommended Palestine’s partition into economically-linked Jewish and Arab polities with Jerusalem and its environs internationalized. Jews in Palestine celebrated the UN resolution, but the Arab states rejected it, as did the Arab Higher Committee, which, led by the mufti of Jerusalem Haj Amin al-Husseini, claimed to speak for Palestine’s Arabs.[26]

Immediately after the UN vote in November 1947, Arab bands loyal to al-Husseini attacked Jewish settlements and Jewish travelers on the roads between them. Jewish units were able to counterattack in April 1948. On May 14, 1948, on the eve of the mandate’s expiration, the new state of Israel declared independence, promising in its declaration to respect the rights of all peoples, Jews, Muslims, and Christians, within its borders.[27] Egypt, Syria, Transjordan, Iraq, as well as groups of armed volunteers from all over the Arab and Muslim world, attacked, aiming to strangle the new state in the crib. Israel survived the war and even expanded its territory. The Arab states ultimately accepted UN-brokered cease-fire agreements in 1949. But they refused to recognize or make peace with the new Jewish state.

There was a paradox in the Middle East concerning the idea of genocide. When Arab and Muslim leaders spoke about warring on increased Jewish immigration into Palestine, or on an emerging Jewish state after- wards, they spoke in apocalyptic and even proto-genocidal terms. During World War II when the mufti Amin al-Husseini was a guest in Adolf Hitler’s Berlin, he urged his followers in the Middle East via short wave radio to undertake genocide. In June 1942, when it looked as though German forces could break through British defenses in Egypt, Arabic language radio urged listers that “This is the best opportunity to get rid of this dirty race. Kill the Jews, burn their property, destroy their stores. Your sole hope of salvation lies in annihilating the Jews.”[28] On the eve of Israeli statehood, even the more conservative Abd al-Rahman Azzam Pasha, the Egyptian head of the League of Arab States, predicted a “war of extermination” against the Jews in Palestine, and a “momentous massacre.”[29]

And yet it was the Zionists whom many Arab leaders viewed as quasi- genocidal, even before the formation of a Jewish state. Perhaps this owed to age-old religious enmities with the Jews as described in the Qur’an and interpreted by Islamic fundamentalists. For the Muslim Brotherhood writer Sayyid Qutb (1906–1966), the Jews were in a cosmic struggle with Islam, and the struggle could only end in destruction of one or the other.[30] Perhaps it was because Arab opponents of Jewish immigration to Palestine viewed Zionism as a brand of racism based on the belief, imputed to the Jews by many, that “they are the chosen people of God.” Some Arab leaders claimed to believe that Zionism’s ultimate aim was the expanse of territory between the Nile and Euphrates Rivers, as God was said to have promised the patriarch Abraham in the Book of Genesis (15:18).[31]

During World War II, the relatively new kingdom of Saudi Arabia took the lead under its aging King Abdul Aziz bin Rahman Al Saud. The king’s chief adviser, Sheikh Yussuf Yassin, a devout Muslim and anti- colonialist, viewed Abdul Aziz as a potential leader of the Arab world. As the kingdom was heavily dependent on United States aid to develop its oil deposits, President Franklin D. Roosevelt hoped to convince Abdul Aziz to support the migration of Jewish refugees to Palestine after the war. In April 1943, however, the king rejected the idea in apocalyptic terms. “We demand,” he wrote the president, “that the Arabs not be exterminated for the sake of the Jews.” As the outlines of the Holocaust were known in the Arab world by this time, this choice of words is still stunning.[32]

In Roosevelt’s historic meeting with Abdul Aziz on the USS Quincy in February 1945, the president seemed, at least in the written protocol, to side with the Arabs against Jewish leaders.[33] But Roosevelt died in April, and President Harry Truman alarmed the Arab world by favoring increased Jewish immigration to Palestine after World War II. The Saudi sense of betrayal—the king later said that if Roosevelt had lived “there would not have been all this trouble with the Jews”—might explain the surprising fact that the first draft of what became the Genocide Convention actually came from the Saudis in November 1946.[34] The Saudi draft defined genocide as the “mass killings of a group, people, or nation,” but also as the “planned disintegration of the political, social, or economic structure of a group, people, or nation.” The second clause surely appealed to Lemkin. But what did it mean to the Saudis?

The Saudi draft featured the “Systematic moral debasement of a group, people, or nation,” as well as “Acts of terrorism committed for the purpose of creating a state of common danger or alarm in a group, people, or nation with the intent of producing their political, social, economic, or moral destruction.”[35] The reference to terrorism seemed here to point to operations by the Revisionist Zionist group Irgun Zvai Leumi (Irgun), the National Military Organization, an irregular force under the command of Menachem Begin in 1946, and by the smaller and more extreme Lohamai Herut Israel (Lehi), Fighters for the Freedom of Israel, which broke off from the Irgun in 1940. Irregulars comprised both groups, operating outside the ambit of the Haganah, the primary Jewish defense militia that in 1948 became the Israel Defense Force (IDF).

A decade earlier during the Arab Revolt led by Amin al-Husseini, Arab terrorists attacked British officials and Jewish settlements, busses, and the like. The Haganah defended the latter. Beginning in November 1937 the Irgun retaliated against Arab civilian targets as a means of “active defense,” that is, to deter against more Arab attacks against Jews. There were some thirty-four such Irgun attacks between 1936 and the end of the Arab revolt in 1939. It is noteworthy that Irgun methods were deeply unpopular with the Zionist mainstream, and that even Revisionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky was ambivalent. It is also of note that the Irgun attacks provided no deterrence. Arab attacks on Jewish civilians continued regardless.[36]

But these Irgun attacks ended when the Arab revolt did. When the Saudis were writing their genocide convention draft in November 1946, the Irgun and Lehi were in full revolt against the British authorities in an effort to end British rule. The Irgun, with increasing Haganah cooperation, began in 1944 with attacks on British immigration offices, tax offices, and police stations, including some in Arab areas. The culmina- tion was the Irgun bombing of the British headquarters in Jerusalem’s King David Hotel in July 1946, which killed 91.[37] As late as 1965, Syrian writer Fayez Sayegh, who founded the Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center in Beirut, argued in his book Zionist Colonialism in Palestine, that Zionist terror was aimed at anyone who worked for the peaceful coexistence between Jews and Arabs.[38] In fact the revolt was increasingly popular with Jews, not because it fought against a peaceful solution, but because it rejected the tight British restrictions on immigration that had begun in 1939 and continued throughout World War II.

Grouping Irgun terrorattacks underthedefinitionofgenocidein 1946, especially as the Irgun targeted a governmental entity rather than ethnic or national group, was truly a stretch. The Saudi proposal was rejected. Ironically had acts of terror as outlined by the Saudis been incorporated under the Genocide Convention, that document would have prohibited as genocidal the countless terror attacks undertaken by later Palestinian Arab organs that were dedicated to the destruction of Israel. The charters of both the Palestine Liberation Organization (1968) and Hamas (1988) call for the eradication of Israel as a Jewish state through system- atic violence.[39] Whatever the inability of the UN General Assembly to define “terrorism” over the years, these documents are unambiguous.[40]

There was another attempt to link Israel to the Genocide Convention during its drafting. In an October 1948 meeting of the UN Legal Committee, which completed the draft convention for consideration by the General Assembly, Syrian delegate Salah Eddine Tarazi insisted that Article I, which defined genocide as “committed in time of peace or in time of war,” should be expanded by the phrase “or at any moment.” The reason, Tarazi said, was what he insisted was Israel’s illegal status. The UN partition resolution on its own, he said, did not create a state; it only recommended one. Thus, the Arab states’ intervention in May 1948 was “not a war” with another state, nor had it occurred “in a time of peace.” Rather it was an attempt at “restoring law and order” in Palestine. And whatever Israel was, Tarazi said, “the Jews had committed atrocities against Arab civilians during the campaign, and those crimes deserved to be punished.”[41] This phrasing that implied Israel’s non-existence was rejected, as Israel was recognized by several UN states by October 1948. including the US and the Soviet Union.

But Tarazi was not finished. The Syrians also made a proposal to expand the definition of genocide under Article II to include “Imposing measures intended to oblige members of the group to abandon their homes in order to escape the threat of subsequent ill treatment.”[42] On October 23, Tarazi asked that it be included, because, as he put it, “. . . any measures directed towards forcing members of a group to leave their homes should be regarded as constituting genocide.” This crime, he said, was “far more serious than ill treatment.”[43] Tarazi referred to the flight and expulsions of Palestinian Arabs during the fighting over a Jewish state. The process began in April 1948 as Jewish forces were turning the tide against the Arab bands attacking Jewish settlements.

By the time Tarazi spoke in October 1948, there were about 400,000 Palestinian Arabs displaced from Israeli-controlled territory, though the number increased to about 750,000 by the time of the 1949 cease-fires. The refugees were located in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, the Gaza Strip (under Egyptian occupation), and the West Bank (occupied and annexed by Jordan). The Palestinian refugees became the lynchpin of an elusive peace settlement. The Israeli government refused their return. As the Arab states refused to make peace, the refugees were a security risk. Nor would the Arab states resettle them, even with the promise of developmental aid from the United States, as this implied the recognition of Israel’s existence.

The collapse of Palestinian civil society in 1948 is referred to today by Palestinian Arabs as the Nakba, meaning the Catastrophe. Some scholars have insisted that the Nakba was planned in advance by Zionist leaders, that it was thus genocidal, or that it should form a distinct legal category within the broader concept of genocide.[44] But in terms of criminality, historian Benny Morris has shown that there was no pre-war Zionist plan to expel the Arabs, nor was there a systematic policy of expulsion during the fighting. Well-to-do Arab families began leaving the cities in December 1947 in anticipation of war; and from April 1948, hundreds of thousands more Arabs fled their towns and villages in panic in the face of Israeli advances. This panic was accentuated by occasional atrocities against Arab civilians as well as tales of rape in Arab radio propaganda. Once the Arab states invaded in May 1948, Israel’s war became one of survival. Some Arab populations, particularly in villages and towns situated on critical roads, were forcibly expelled, particularly as these localities often housed Arab militias. Some 150,000 Arabs were left in place in the new state.[45]

And yet the UN legal committee rejected the Syrian amendment to the Genocide Convention. One can argue that certain delegations had their own reasons for doing so. The Soviets, Americans, and British all signed off on the 1945 Potsdam Declaration, which legitimized the expulsion of some twelve million Germans from Eastern Europe.[46] India rejected the amendment as well, perhaps as it and Pakistan were engaged in mass population movements involving some fourteen million people following the partition of the subcontinent in 1947.[47]

But the Legal Committee as a whole had aimed to define genocide not by expulsions, but by physical reduction of populations, either by killing or by preventing births. Even the most brutal expulsions accept the continued existence of the expelled someplace else. As the Cuban delegation put it, the Syrian amendment was “interesting,” but did not fall under the definition of genocide, “which was, essentially, the destruction of a human group.” Even the Egyptians, then at war with Israel, argued that the Syrian amendment, which ultimately concerned displaced persons, “went beyond the accepted idea of genocide.” The committee rejected the amendment by a vote of twenty-nine to five with eight abstentions.[48]

The Genocide Convention was politicized during the Cold War, often by the communist world, the New Left, and their various fellow travelers. Thus, the Soviets, the Chinese, and the so-called Russell Tribunal, a “people’s court” developed in 1966 by British philosopher Bertrand Russell and French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, all accused the US of geno- cide in Vietnam.[49] The Soviets and Black power organizations in the US also characterized racial violence in US cities as genocidal. On the other hand, allies of truly lethal regimes tended to wink at mass killing. The bloody Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia killed some two million people between 1975 and 1979. But neither the Chinese, who were allied with the Khmer Rouge, nor American leftists, who praised the Khmer Rouge’s revolutionary zeal, could summon critique over the carnage.[50]

No state was charged more often with genocide than Israel. Each war fought by the Israelis brought genocide accusations, some long after the fact. But previous to Israel’s contemporary wars with Hamas, no conflict generated the accusations of the First Lebanon War of 1982. There had been Palestinian refugee camps in Southern Lebanon since 1948. But following the Kingdom of Jordan’s expulsion of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from that country in 1970, the PLO, under its executive committee chairman Yasser Arafat, based itself in Lebanon, with its headquarters in Beirut.

The PLO was an umbrella organization for numerous groups that saw themselves as revolutionary and which espoused terror, ranging from Arafat’s group Fatah (which dominates the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank today) to George Habash’s People’s Front for the Liberation of Palestine. The PLO charter in 1968 denied all Jewish connection to Palestine and called not for a two-state solution but for the dismantling of Israel through armed struggle and what it called “commando action.”[51]

By the late 1970s the PLO constituted a mini-state within Lebanon. It benefitted from the fragmentation of Lebanon, the stability of which depended on a delicate balance between Christians and Muslims. The PLO feuded with Maronite Christian militias that had been associated with the Israelis. Syria, meanwhile, established a military presence in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley that featured thousands of troops and Soviet surface to air missile batteries. They prevented the possibility of Lebanese elections, which might bring a government to power that would demand Lebanon’s independence.

The PLO was also embedded into the Cold War. In the 1970s and 80s it received increasing stockpiles of weapons from the Soviet Union and its East European satellites, including rocket launchers, artillery, rocket-propelled grenades, machine guns, and even tanks and anti-aircraft weapons.[52] From bases in southern Lebanon, which included Palestinian refugee camps there, the PLO launched countless attacks into northern Israel and other attacks against Israeli officials in Europe. The targets were always civilians. Attacks included ghastly terror raids like the March 1978 coastal road massacre, wherein Palestinian ter- rorists hijacked a bus on the road between Haifa and Tel Aviv, killing thirty-eight Israelis including thirteen children. It also included numerous launches of Katyusha rockets into northern Israeli settlements that killed some residents while driving many more into shelters.

The Israeli invasion of Lebanon that commenced on June 4, 1982 suffered from defense minister Ariel Sharon’s overly ambitious strategy. It aimed first to destroy PLO military infrastructure in Southern Lebanon, a limited aim of 40 kilometers that could be justified internationally. Israeli planning also called for the elimination of the PLO’s bases and political leadership in Beirut with the help of Christian militia there, the expulsion of Syrian forces from the Bekaa Valley, and the establishment of a friendly Christian-led government in Lebanon. These more ambitious stages were to flow from the initial aim and yet were to appear unplanned to the outside world. Sharon convinced Prime Minister Menachem Begin that the war would be over quickly.[53]

But the fighting was tougher than the Israeli leadership expected. Even the initial advances in southern Lebanon, which the Israelis thought would take three days, were slowed by PLO resistance, as Palestinian fighters retreated to the main refugee camps on the outskirts of Tyre and Sidon. The drive on Beirut was also slowed by PLO defenses. The Israelis responded with artillery bombardment, air raids, and a siege of Beirut that lasted seven weeks from June 26 to the US-brokered cease-fire of August 12. The aim was to kill PLO leaders, including Arafat, via attacks on the apartment buildings where they lived and met. A US brokered cease-fire, ultimately agreed to by Arafat, provided safe passage for the PLO out of Lebanon and to Tunisia.[54]

Genocide accusations against Israel flooded the UN General Assembly’s special emergency special session on “the Question of Palestine.” This special session, which convened initially in July 1980, has its own history. It convened owing to various shortcuts through established UN procedures. Having never been formally ended, it reconvened on June 28, 1982.[55] Virtually all UN member states condemned the invasion and the shelling of Beirut, and virtually all called for a halt in the fighting and Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories. The specific genocide accusations flowed specifically from delegations from the communist world, from the Arab states, and from the Movement of Non-Aligned Countries, all of which had adopted a dim view of Israel since 1967 as a racist and colonial state. These states had already in 1975 voted for General Assembly Resolution 3379 condemning Zionism as “a form of racism and racial discrimination.”[56] Now they jumped aboard the genocide accusation.

It should be noted that the genocide accusation was a form of warfare undertaken out of embarrassing inability to aid the PLO militarily. The Soviets had been embroiled in Afghanistan since 1979 and could not even help the wobbling government next door in Poland. And the extensive caches of PLO weapons manufactured in and imported from Eastern Europe and uncovered repeatedly by the Israelis were a major embarrassment.[57] Meanwhile Arab and Muslim populations in numer- ous states sympathized strongly with the Palestinians. But Jordan had forcibly expelled the PLO twelve years earlier, and Egypt had just implemented its 1979 peace agreement with Israel. Syrian forces, meanwhile, were chased out of the Bekaa Valley by Israeli fighter jets five days into the Lebanon War and Damascus quickly signed a cease-fire with Israel.[58] Anti-Israeli statements were the best these governments could do.

Thus, the genocide accusations of 1982 were an expression of wartime solidarity with the PLO because such expressions were the only option. As Lebanese representative Ghassan Tueni put it on June 26, “So many speakers have described the holocaust and genocide [in Lebanon] that my delegation’s testimony here would be superfluous. May I, however, say once more how appreciative and how grateful we are for such manifestations of support and friendship?”[59]

But the statements were also laced with antisemitic tropes. Today, the Gaza Ministry of Health inflates casualty figures, especially regarding women and children, a trend which should give pause to anyone charging genocide.[60] It is instructive that in 1982, there was a similar inflation of casualty figures. At the September 1982 Arab summit, PLO chairman Yasser Arafat claimed there were 49,600 civilian dead. A Lebanese study after the war counted 17,825, a number that combined military and civilian deaths.[61] PLO representative Zuhdi Labib Terzi was the first to speak. He claimed that the Israelis were victimizing nearly a million children in Lebanon as a primary war aim.[62]

Others took the cue. The themes of blood and choseness appeared repeatedly. Mohammed Abulhassan of Kuwait decried “Begin and his bloodthirsty agents.”[63] Jasim Yousif Jamal of Qatar claimed that Israeli soldiers were motivated by “their thirst for Arab blood, be it the blood of a child, a woman, or an old person,” as they were “seeking the so-called security of the ‘chosen people,’ as they so arrogantly state.” Jamal also accused the Israelis of using napalm.[64] Salah Omer al-Ali of Iraq charged that Israeli soldiers had “a thirst for blood.”[65] Mohammed Sallam of Yemen claimed that “the Zionists are striving to send all people to hell so as to ensure that only ‘the chosen people of God’ may exist on earth and Israel may reign supreme over all.”[66]

The theme of government manipulation also received a full airing. Awad Burwin of Libya claimed that US officials “have been subjected to pressure by the Zionist entity . . . the number of Jews among the voters in New York, California, and other places where there are large Jewish communities is significant. That is why they can exert pressure on the United States . . . to support Israel.”[67] Rodrigo Malmierca of Cuba added that “These are not the times in which the world can be deceived by well-orchestrated press campaigns depicting the aggressor as the victim. The plain truth is that Israel intends to commit genocide against the Palestinian people.”[68] Hazem Naseibeh of Jordan also decried “[an] Israeli campaign already in operation to brainwash an outraged world.”[69] Mohammed al-Mosfir of the United Arab Emirates took it all a step further. “There is a Zionist group,” he said, “which dominates the capital and mass media and exercises its influence on the elections of the executive and legislative authorities in the United States of America.[70]

But perhaps the most telling statement came from Adnan Omran of the Arab League. It is ironic that Omran was a Syrian diplomat who later served dictator Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashir as minister of information. He was surely embarrassed by the Syria’s defeat in the Bekaa Valley, the cease fire afterwards, and the lack of Syrian aid to the PLO. But there was even more to deflect. Just months before Israel invaded Lebanon, Syrian army and militia forces besieged the Syrian town of Hama, a stronghold of the Muslim Brotherhood, which had violently opposed Hafez al-Assad’s regime. After nearly a month, Syrian forces carried out an anti-Sunni massacre that killed at least 10,000 and perhaps as many as 40,000 over two weeks of destruction.[71] The massacre rated not a mention in the General Assembly in 1982, save for when Israeli ambassador Yehuda Blum pointed out the irony.[72]

Omran, in any event, clarified the problem for everyone. Israel was not a state committing a genocide. Israel was a genocidal state. “[T]he structure of the Israeli entity,” he said

is built on the tenets of Zionist racist settler ideology and the premise of a chosen people, a premise that makes Zionist decision-makers believe that they and their people alone are superior to all other people on earth, that they have the right to commit the crime of genocide, thus perpetrating in a skillful reproduction all the crimes of Nazism The premise of Zionist racial superiority—identical to the Nazi ideology of racial superiority— bestows on those possessing the military might the right to draw political maps according to their expansionist plans.......... What difference is there between the Israeli bloodbaths inflicted on thousands of innocent children and civilians in Lebanon today and the Nazi holocaust?”[73]

Specifically, Omran said, Zionist ideology “justifies uprooting of Pal- estinians, generation after generation,” beginning with the displacement of Palestinians in 1948. Omran thus foreshadowed by two decades the ways in which settler-colonial theory linked the displacements of 1948 with all subsequent Israeli wars.

It was not until September, however, that a General Assembly resolution accused Israel of genocide. The trigger was the war’s darkest episode, the massacre in the Palestinian Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. As Israeli forces advanced toward Beirut, units of the Phalange, the Maronite Lebanese Christian militia allied with Israel, was ordered to clear PLO fighters from the Sabra and Shatila camps, from which Israeli forces had taken fire. In response to the recent assassination of Lebanon’s Christian president Bashir Gemayel, the Phalange militiamen killed a number of fighters and a still-unsettled number of Palestinian civilians. The Red Cross estimated 1,000 dead. Arafat claimed 3,200.[74]

The Sabra and Shatila massacres provoked outrage both in Israel and globally. The Israeli government convened an official commission under supreme court president Yitzhak Kahan. The commission put the primary responsibility for the massacre on the Lebanese militia. But the Israeli officers involved, the commission said, were “indirectly responsible” owing to dangers that should have been foreseen. Ariel Sharon in his capacity as defense minister was determined to have borne personal responsibility for ignoring the probability that revenge motives on the part of Christian militiamen could lead to bloodshed and for not taking measures to stop it.[75] The committee recommended his dismissal as defense minister, and after initial resistance, Sharon resigned.

After the massacres, the Seventh Emergency Session of the General Assembly shifted into a higher gear. In the meeting of September 24, all states, including Israel itself, condemned the massacre. But the Arab, non-aligned, and communist states saw genocide rather than a terrible incident. Soviet representative Oleg Troyanovsky reiterated that “what Israel is doing is called genocide. It is genocide as regards the Palestinians, as was carried out by the Hitlerites vis-à-vis other peoples, including the Jewish people” Harry Ott of East Germany agreed that Sabra and Shatila “prove that state terrorism and genocidal crimes are an integral part of Israel’s policy.” PLO representative Zuhdi Labib Terzi compared Sabra and Shatila to Auschwitz and Beirut to the Warsaw Ghetto and asked “How long will the world sit and watch the systematic elimination of the Palestinian people?” Libya, like other states even before the massacres, called for an international tribunal modeled on Nuremberg.[76]

In December the UN General Assembly in Resolution 37/123 D stated that the massacres at Sabra and Shatila were “an act of genocide.”[77] The vote was 123 for, zero against, and 22 abstaining. Legal scholar Antonio Cassese notes that the resolution was not undertaken for humanitarian reasons but rather political ones. The Cuban delegation, which introduced the resolution, did not discuss the constitutive elements of genocide as per the 1948 convention. It simply said that the resolution was “self-explanatory.” No debate followed on the facts or the legal implications of classifying the massacres a genocide. The resolution, Cassese says, “reveals an intention to use the resolution as a political instrument and a tool for propaganda.”[78] In his definitive study Genocide in International Law, William A. Shabas agrees that there was no legal precision to the resolution. Genocide as a term, he said, was “obviously . . . chosen to embarrass Israel.”[79]

It did not end there. In August 1982, a privately-funded International Commission of Inquiry constituted itself under Seán MacBride, formerly of the Irish Republican Army and now president of the International Peace Bureau in Geneva, and Richard Falk, then an activist professor of international law at Princeton University, and later (2008–2014) the UN Human Rights Commission’s Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in the Palestinian Territories Occupied since 1967. The six-man commission’s terms of reference focused entirely on investigating Israeli, not PLO, violations of international law. The investigation took twenty-two days and questioned numerous witnesses, five from the PLO and none from the Israeli government.[80]

The MacBride commission’s subsequent report condemned Israel for aggression in Lebanon. It also argued that Israel had violated the Hague and Geneva Conventions by targeting refugee camps, even though the commission itself admitted that “these camps often contained combat- ants and stores of munitions.”[81] It viewed the Sabra and Shatila massacres not as isolated incidents but part of a “pattern” of violence that stretched from the killing of civilians at Deir Yassin in April 1948 by Irgun and Lehi detachments to the present.[82]

But the MacBride commission also discussed genocide, even though genocide was not in the terms of reference. It recommended that “an authoritative international institution” should investigate whether “Israeli policies and conduct” amounted to that crime.[83] The commission was divided on whether to accuse Israel of genocide, but a majority of the committee thought that the accusation was warranted and an appendix to this effect is included in the report. The majority understood the gravity of this step, as genocide was “one of the most serious allegations which can be made.”[84]

Yet in order to charge Israel with genocide, the majority had to bend the legal definition of the term. On the one hand, they contradicted many of the arguments in the UN General Assembly debates by claiming that “The particular form of genocide as applied to Palestinians does not appear to be aimed at killing the Palestinians in a systematic fashion.” On the other hand, the majority asserted that, “The definition of genocide is not limited to the formula adopted by the United Nations in 1948.” Specifically, Israel had adopted measures “to destroy the national culture, political autonomy and national will in the context of the Palestinian struggle for national liberation and self-determination.” Insofar as this definition included national culture, it hearkened back to Lemkin’s initial ideas concerning how genocide might be defined. But this conception of Lemkin’s was not adopted by the UN in 1948 and is nowhere to be found in the Genocide Convention. The MacBride Commission admitted the leeway it had taken when it said, “what the majority of the Commission has in mind is a different form of genocide.”

This different form of genocide hearkened to UN resolutions concerning national liberation movements, which were absent from UN debates in 1948. The commission cited General Assembly Resolution 2105 (1965), which recognized “the legitimacy of the struggle by the peoples under colonial rule to exercise their right to self-determination.” That resolution was issued in the context of decolonization in Angola, Rhodesia, and Guinea-Bissau, but in 1974 the General Assembly issued Resolution 3236 recognizing the Palestinian right to self-determination and the right of all Palestinians to return to their homes lost since 1948. Resolution 3237 invited the PLO to participate in all UN General Assembly meetings as an observer, and Resolution 3375 of 1975 recognized the PLO as “the representative of the Palestinian people,” which should participate in deliberations concerning the Middle East.[85]

For the MacBride commission, these steps, and surely Yasser Arafat’s 1974 address to a rapturous General Assembly, which decried Zionism as racist, colonialist, and illegitimate, cemented the PLO’s status as a national liberation movement which “enjoys a special status in international law.” In truth, General Assembly resolutions do not carry the force of law at all. The UN Charter itself only gives the General Assembly the power to make recommendations to the Security Council.[86] The MacBride commission, moreover, ignored the PLO’s charter, which called for Israel’s destruction, and it had nothing to say concerning never-end- ing terror attacks by the PLO’s various groups.[87]

Serious international law journals did not take the MacBride com- mission’s report seriously.[88] But the Middle Eastern Studies world did. The Journal of Palestine Studies and other journals such as Race and Class published long excepts from the 282-page report as a “special document,” including many of the comments on genocide.[89] Given the acclaim from these quarters in 1983, it is curious that no one accusing Israel of genocide after 2023, particularly from within the UN, cites Israel’s earlier “genocide” of 1982. It is possible that no one wants for it to be discussed. For if anyone were to read the tendentious General Assembly debates of that year, it would be an embarrassment to both the UN and to those making similar accusations today.

The Cold War is over. The culture wars have not receded. Today’s genocide charges are different thanks to settler colonial theory, which developed in the 1990s and greatly expanded in the 2000s. Adam Kirsch’s very fine work on settler-colonial theory describes it as more of an ideology than an academic theory fueled by painstaking inquiry.[90] In a seminal 2006 article, anthropologist Patrick Wolfe defines settler colonialism as a process of invasion, mass settlement, and the “elimination of the native.”[91] Wolfe also argues that “the question of genocide is never far from discussions of settler colonialism.”[92] Thus, settler-colonialism and genocide go hand in hand. But Wolfe’s is a version of genocide redefined from the UN Genocide Convention. For Wolfe and other settler colonial theorists, genocide is not so much a single event or even a series of events but a societal structure.

Critical, too, is that Wolfe, like many others, views the Holocaust not as a means for understanding genocide but actually an impediment, because “as the unqualified referent of the qualified genocide, it can only disadvantage Indigenous peoples.” Wolfe’s term “structural genocide” also consciously avoids constraints of time and place and even of life and death. Indeed, killing for Wolfe can be in abeyance during an ongoing genocide, because the necessities of the settler colonial genocidal structure will inevitably recur when the settler colonialists need more land.

There is something dishonest about Wolfe’s arguments. In his 2006 article, he cites Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, as saying, “If I wish to substitute a new building for an old one, I must demolish before I construct.” This Wolfe says, “reveals that settler-colonialism destroys to replace.”[93] Wolfe incorrectly attributes the statement to Herzl’s novel Altneuland, which imagines a futuristic paradise for all peoples in Palestine.[94] But Herzl’s statement actually comes from his 1896 treatise Der Judenstaat [The Jewish State], which is credited with the positing the foundation of political Zionism. More importantly, Herzl’s mention of “demolition” refers not to Palestine at all, but rather the way in which Herzl thought European Jews saw themselves in the late nineteenth century, as a beleaguered minority incapable of defending itself.[95]

Wolfe’s misattribution to Altneuland is interesting in itself. Wolfe never corrected it in his subsequent work on Zionism because he never returned to the original source. Wolfe’s quote from Herzl has been repeated in many books and journal articles on Palestine that examine the conflict from a settler-colonialist perspective. All attribute Herzl’s words, as Wolfe did, to Altneuland. Despite their conviction that Zionism is today’s most pernicious settler colonial doctrine, and despite the belief that the evidence for Zionism’s will to erase lies in the foundational texts of political Zionism, no scholar condemning Zionism has bothered to read the text for themselves. Wolfe and other practitioners of settler colonial theory, it would seem, feel no need to do so.

The lack of factual precision within the intellectual structure of set- tler colonial theory is widespread. Lorenzo Veracini is the doyen of settler colonial theory today. He is a historian in Australia and editor of the journal Settler Colonial Studies, which he founded in 2011 and which published special issues on Palestine in 2012, 2015, and 2019. In what Veracini calls “a densely argued essay” on Israel and Settler Colonialism from 2019, Veracini calls for “privileging the theoretical over the empirical,” a phrase which should make any scholar wince.[96]

In this vein we can also consider sociologist Martin Shaw, a contemporary genocide theorist who argues that the question “What is genocide?” should be replaced by the question “What should genocide mean?” The constitutive criminal elements, Shaw says, mass killing and intent, are not sufficient. Genocide ought, Shaw says, be defined by asymmetri- cal social structures.[97] Thus, Shaw’s complaint from January 2024 in a journal article on the Gaza war titled “Inescapably Genocidal” that the Genocide Convention allows “defenders of Israel’s violence to argue that the criteria has not been met,” because they can “hew closely to a tick-box exercise.” What matters for Shaw is not intent, casualties, or case law from pervious genocide cases, but the crippling of Gaza, which, he says, provides “scope for a sociological concept of genocide that is broader than the prevailing legal definition.”[98] So defined, genocide becomes the only crime in the corpus of international law where mens rea (the guilty mind) and actus reus (the guilty act) are not relevant.

The notion of structural genocide can be applied more broadly than one thinks, even to the Hebrew Bible. Biblical Scholar Jeremy Cott condemns the idea of divine election as “the most pernicious notion inherited from biblical tradition,” because one who believes he is chosen "tends to want to do away with everyone who is not.”[99] More to the point, the killing of the Canaanites and the Amalekites in the Books of Joshua and Samuel (and the earlier references to these peoples in Exodus and Deuteronomy) serve as structural base.

Marxist scholars weighed in decades ago. G.E.M. de Sainte Croix, an historian of antiquity, wrote in 1981, “I know of only one people which felt able to assert that it actually had a divine command to exterminate whole populations . . . namely Israel.”[100] It is an oft-cited quote in the settler colonial anti-Zionist Biblical genre.[101] Nur Masalha, a Palestinian sociologist who has wandered into the world of biblical study, argues that there never was an ancient Israel, the considerable archeological evidence notwithstanding. Still, he says, the “conquest narrative” of the Canaanites, has still served “as a guide for Zionist and Israeli state policies toward the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine.”[102] Activist scholar Bruce Fisk argues further that the “Canaanite Genocide” must be “in conversation” with the Nakba.[103]

All of the above is background to the current obsession with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s mention of Amalek in a speech of October 28, 2023. Netanyahu quoted from Deuteronomy 25:17: “Remember what Amelek did to you.” The line immediately became “proof” not only of Israel’s genocidal intent to destroy the Palestinians in Gaza but also of Israel’s genocidal nature. The Electronic Intifada decried “Netanyahu’s invocation of the genocidal biblical story of Amalek.” Writing for Aljazeera, historian Raz Segal called it a “crude and dangerous weaponization of religion,” as perpetrators of genocide “always see the group they are attacking as posing an existential threat.”[104] Holocaust historian Omer Bartov warned in the New York Times that “this deeply alarming language” could easily turn into “genocidal action.”[105] In January 2024, Deuteronomy 25:17 weirdly became a pillar of South Africa’s genocide accusations against Israel before the International Court of Justice.[106]

There is a lot to unpack here, but the following is worth noting. Netanyahu’s October 28 speech mentions several figures in ancient Jewish history, including Judah Maccabee and Bar Kochba, both of whom rebelled against imperial rule. Netanyahu also reminded his listeners that the Israeli Defense Forces in Gaza worked “to avoid harming non-combatants,” and he urged Gaza’s civilians to go to more safe areas. Whatever one thinks of Netanyahu, those who cite his speech as incitement to genocide do not mention these passages.[107] There is more. In January 2010 on Holocaust Remembrance Day, Netanyahu, from the ruins of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp, referenced Amalek when discussing Iran, which was working on the development of a nuclear arsenal while denying the Holocaust and calling for Israel’s destruction.[108] Even before this particular mention, the anti-Zionist website Mondoweiss predicted that the mention of Amalek “would seem to prescribe genocide for Iran.”[109] The Iranian genocide never happened. In the meantime, if one wants to know how the genocide accusation is antisemitic, one can begin with the accusers’ insistence that Judaism itself is genocidal.

The Islamic Resistance Movement, commonly known as Hamas, was founded as a Palestinian wing of the Muslim Brotherhood in 1987. Hamas was predicated on religious fundamentalism and absolute opposition to the two-state solution and financial corruption associated in these years with Arafat’s PLO. Hamas’s covenant of 1988 calls for Allah’s help in destroying Israel, attributes to the Jews everything from blasphemy to attempts to rule the world, highlights its struggle with the Jews as “very great and very serious,” and calls for the killing of Jews on the Day of Judgment.[110]

Suicide bombings and other attacks by Hamas and associated movements on Israeli settlers and soldiers in the Gaza Strip led in 2005 to the end of the Israeli military occupation that began in 1967. Despite the insistence by anti-Zionists that the Gaza Strip is still under effective occupation, the occupation ended in the legal sense. Hamas violently took full control of the Gaza Strip from the Palestinian Authority in 2007. With the help of Iran, it smuggled weapons into Gaza by sea and through an extensive network of tunnels which traverse Gaza’s underground and reach into Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Even before Hamas took full control, it launched rocket attacks and small ground operations against Israel.

Israel responded in 2007 with a combination of a land siege, closing the Israeli crossings into Gaza, and then in 2009 a naval blockade. Both aimed to halt the flow of strategic materials such as concrete, fuel, and weaponry. The law here is complex and inconclusive. The duration of the Israeli siege and blockade of Gaza are unprecedented, and though neither is total, both are restrictive. One can argue about proportionality and collateral damage to civilians.[111] The 1977 Protocols to the 1949 Geneva Convention are clear in their prohibition of deliberate starvation of civilians as a war aim. But starvation was never a problem in Gaza, and deprivation of certain goods, while a hardship, is not starvation.[112] A 2010 report by the UN Secretary General’s Panel of Inquiry after the 2010 “freedom flotilla” incident concluded that the naval blockade was a legal exercise of self-defense, and it applauded Israel’s easing of restrictions that year concerning the land crossings.[113]

Regardless, the current genocide libel began in 2007 with the land siege. Activists labelled the siege an instrument of “slow genocide.” Articles appeared on various platforms with titles like “Israel’s Slow-Motion Genocide,” “A Slow Steady Genocide,” “European Collusion in Israel’s Slow Genocide,” and so on.[114] The most influential essay was by Rich- ard Falk, the coauthor of the MacBride commission report and soon to become the UN Human Rights Council’s special rapporteur for Palestine in 2008. Falk’s 2007 article, “Slouching toward a Palestinian Holocaust,” argued that the blockade was “a holocaust in the making.” Falk was silent concerning his accusations that Israel committed genocide in Lebanon in 1982.[115]

Owing to his position, Falk’s work got the attention of Omar Barghouti, the Palestinian activist who emerged as the head of the Boycott, Divest, Sanctions (BDS) movement.[116] In his 2011 book BDS, Barghouti cites Falk along with settler colonial theory and a particular reading of the Genocide Convention, to discuss what he calls, “Israel’s hermetic siege of Gaza, designed to kill, cause serious bodily and mental harm, and inflict conditions of life calculated to bring about . . . gradual physical destruction . . ” This, Barghouti says, “qualifies as an act of genocide, if not yet all-out genocide.”[117]

The Global Hunger Index, a peer-reviewed annual report prepared by several entities, did not mention Gaza in 2011 when Barghouti was writing, or in years hence.[118] In fact the population in Gaza grew between 2 and 3 per cent each year.[119] The GHI uses a number of metrics such as the percentage of the population undernourished and child stunting and child mortality that are not used by NGOs such as Oxfam, which today accuses Israel of causing a famine.[120] More to the point, while “slow genocide” can fit under the Genocide Convention’s provision for creating conditions that can lead to the destruction of the group, the framers of the Convention had the Warsaw Ghetto in mind, where mass death by starvation actually occurred within a year of the ghetto creation.

In the meantime, those charging genocide began working on the accusation from the first of the Gaza Wars, Operation Cast Lead in 2008–09. Demonstrators in Paris accused Israel of genocide during the operation.[121] But most attention after Cast Lead went to the UN fact-finding mission under the highly-respected Jewish South African justice Richard Goldstone and the mission’s subsequent report, labelled the Goldstone Report, which accused Israel of collective punishment of Gazan civilians, and thus violations of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 and the additional protocols of 1977.[122] After examining Israeli targeting, Goldstone later retracted the conclusions of the report that bore his name.[123] Meanwhile, the furor over the Goldstone report obscured other reports that followed Cast Lead. Chief among these was the Dugard Report.

John Dugard is a South African jurist. Since 2023, he has been part of the South African team charging Israel with genocide before the International Court of Justice. He had served as UN special rapporteur for Palestine from 2001–2008, preceding Richard Falk, and he retained the respect of UN officials thereafter. In 2009 he headed a team called the “Independent Fact-Finding Mission Mandated by the League of Arab States to Investigate Israeli Crimes and Human Rights Violations Perpetrated During Israel’s Offensive on the Palestinian People in the Gaza Strip.” Looking back this year at that mission’s report fifteen years ago, Dugard remembered unanimous insistence among those in this mission that Israel had committed genocide during Cast Lead. Dugard’s reply in 2009, he remembered in 2024, was that such an accusation was taboo. “My God,” he remembers himself saying, “you cannot accuse Israel of genocide.”[124]

The Dugard report actually concluded that Israel committed war crimes, crimes against humanity, “and possibly genocide.” The report charged Israeli forces with “killing, exterminating and causing serious bodily harm to members of a group—the Palestinians of Gaza.” But Dugard’s team could not determine government intent. The report thus urged the Arab League “to recommend to its members that they consider instituting legal proceedings against Israel in accordance with Article 9 [of the Genocide Convention]” because there was “a prospect that such a claim might succeed.”[125] In his own capacity as Special Rapporteur for Palestine, Richard Falk lauded the Dugard report as highly reliable.[126]

This trend increased after the next Gaza War, Operation Protective Edge in the summer of 2014. This time the investigative body was the so-called Russell Tribunal, created in 1966 as a people’s tribunal by Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Sartre. In September 2014 the Russell Tribunal held an “extraordinary session on Gaza.” The “jury” included John Dugard (who also served as a witness) and Richard Falk (still the UN special rapporteur for Palestine), but also Hamas-supporting activist Christiane Hessel and South African activist and later security minister Ronnie Kasrils. The latter had compared Israelis to Nazis. After October 7 he insisted that Hamas’s massacres were “a towering military accomplishment” while denying that Hamas killed civilians. Bass-playing antisemite Roger Waters rounded out the tribunal.[127]

The presence of two UN human rights officials on a panel with char- acters like Hessel, Kasrils, and Waters ought to have raised eyebrows in the UN. All the same, the Russell Tribunal announced that it would seriously examine “Israeli policy in light of the prohibition of genocide in international law.” Dugard argued that Gaza was legally “occupied territory,” thus theoretically legitimizing resistance in any form. Rockets and tunneling, Dugard argued, “were the acts of resistance of an occupied people.” Dugard openly compared Hamas to the French resistance in World War II. War crimes and crimes against humanity were to be considered, Dugard said, but genocide had to be considered too.[128]

It is critical to note the permeation of settler colonial theory in the Russell Tribunal’s findings. The tribunal noted that there was a legal definition of genocide for criminal courts, but there were also “alternative, broader understandings of genocide beyond . . . individual criminal responsibility.” The Tribunal thus condemned Israel’s “settler colonial policies based on displacement and dispossession of Palestinians” since 1948, while also arguing that that the “cumulative effect of the long-standing regime of collective punishment,” was designed to cause “the incremental destruction of the Palestinians as a group in Gaza." Yet though the tribunal found Israel guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, it stopped short of genocide, or at least the mention of that term in its judgment. Dugard later lamented the Tribunal’s caution. “There was a lot of support for accusing Israel of genocide,” he said later. “But that was still so taboo ”[129]

What did Dugard mean by “taboo”? Did he mean the broad societal pressure that one might see concerning immorality? In a statement of April 2023, Richard Falk quoted Dugard as stating that the biggest problem in fighting Israeli “apartheid” was “the weaponization of antisemitism.” The problem, Falk concurred, was the working definition of antisemitism by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), which labeled as antisemitic libelous falsehoods concerning Israel but not critique of Israel as such. Zionists, Falk said, had a “powerful punitive tool by which to deflect pro-Palestinian activism by brand-ing adherents as antisemites.”[130] The argument over the 2016 IHRA working definition of antisemitism is beyond the scope of this essay.[131] The point is that for Dugard, it was the Jews who were the impediment to truth. After October 7, John Dugard, despite the carnage in southern Israel and in Gaza, was a happy man. “It’s a relief,” he told an interviewer in June 2024, “to say what it is: Israel is committing genocide.”[132]

As I have written elsewhere, there are many factual and evidentiary problems with the South African charges.[133] But the point to make here is that the genocide accusations of 2023 and 2024 represent a culmination of years-long efforts by everyone from UN special rapporteurs to post-colonial scholars to BDS activists to NGOs such as Amnesty International. And the antisemitic tropes remain. In June 2019, The Electronic Intifada complained that the “UN Lets Israel’s Child Killers Off the Hook Again.” In 2024 the website added tales of Israeli soldiers executing children as young as four.[134] In 2024 the Palestine Global Mental Health Network argued that in Israel’s war in Gaza, “children are directly targeted,” many deliberately shot in the head.[135] And there is no shortage of stories discussing the Zionist manipulation of discourse in the US and other countries aimed at hiding the truth of the “ongoing genocide.”[136]

Critical, however, is that many making the genocide charge have infused the structural interpretation of genocide into the accusation, in effect, expanding the Genocide Convention far beyond its actual text and its intent. A prime example is the March 2024 report, “Anatomy of a Genocide” by the current (and eighth) UN special rapporteur for Palestine, Francesca Albanese, who has held the position since 2022.[137] Even by the jaundiced standards of UN special rapporteurs on Palestine, Albanese is different. Unlike her predecessors, she seeks to be not just a UN official but something akin to a social media influencer. She has a Twitter following of over 350,000, and her Twitter page strangely has the word “Genocide” scrawled across it in blood red, as if the accusation of genocide is a part of her brand, even as she publicly calls herself “a reluctant chronicler of genocide.”[138] Though she tries to sidestep charges of antisemitism today, she claimed on Facebook in 2022 that the US was subjugated by the Jewish lobby while European support of Israel was owing to its Holocaust guilt.[139]

Albanese’s 2024 report asserts that “Settler-colonialism is a dynamic, structural process and a confluence of acts aimed at displacing and eliminating indigenous groups, of which genocidal extermination/annihilation represents the peak.” In “Palestine,” Albanese continues, “displacing and erasing the Indigenous Arab presence has been an inevitable part of the forming of Israel as a ‘Jewish State.’” By using the structural model, Albanese, like many scholars she has surely read, can tie the 1948 Nakba to the current Gaza war, thus binding Israeli history together into a neat, formulaic, genocidal whole. “Israel’s genocide on the Palestinians in Gaza,” she says, “is an escalatory stage of a long-standing settler colonial process of erasure. For over seven decades this process has suffocated the Palestinian people as a group.”

Another recent example of this trend is Amnesty International’s December 2024 report subtitled “Israel’s Genocide Against the Palestinians in Gaza.” There are more evidentiary and factual problems with the report than I can get into now. My interest here is the argumentation. And here the trend again is to meld the criminal constitutive elements of genocide with settler-colonial theory. Thus, one humanitarian solution envisioned by Amnesty was for masses of displaced Gazans to enter not Egypt for temporary shelter, but Israel permanently, “especially since over 70% of Gaza’s population are refugees or descendants of refugees displaced in 1948 and, as such, are entitled under international law to return.”[140]

More interesting though, is this: Amnesty’s conclusion is that Israel’s military responses are disproportionate and that they target civilians as a mode of warfare while inflicting conditions designed to destroy the group. Thus, for Amnesty, the conduct of the war itself is genocidal. But those same allegedly disproportional acts, which were also said to have targeted civilians while destroying infrastructure and cultural sites, were, according to the 2009 Goldstone Report, breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention—war crimes—insofar as they represented a form of collective punishment. Amnesty International’s conclusion charges Israel with genocide and genocide alone. This is unusual insofar as official reports generally list several categories of crimes and the articles allegedly violated. Why were the same alleged infractions war crimes in 2009 and genocide in 2024

Part of what has changed is language, borne of academic writing that has privileged theory over facts while redefining genocide as part of a power structure rather than as a crime with distinct parameters, all the while applying it to Israel while ignoring the far more careful case law concerning genocide in former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and elsewhere. This is why The Electronic Intifada was incensed in May 2024 when ICC prosecutor Karim Khan asked for arrest warrants for Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, but under the categories of war crimes and crimes against humanity, not under genocide.[141]

But something else has changed as well. The spheres of activism and social media today reflect all-or-nothing argumentation, big on slogans and light on precision. The 2014 Gaza War (Operation Protective Edge, July 8–August 26) was the watershed. It coincided with anti-police clashes that followed the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. There was a similar nexus between the 2021 Gaza War (Operation Guardian of the Walls, May 6–21) and the global demonstrations that followed George Floyd’s killing the previous year.[142]

The 1960s idea that those resisting oppression must be in solidarity with one another came to fruition, but now on ubiquitous social media platforms. The 2014 Gaza War saw over 49 million related posts on Twit- ter. The main hashtags were #gazaunderattack, #freepalestine, and so on. Tiktok, the popular online video platform, was launched in 2017. It allows any user, no matter how ill-informed, to be a news pundit while reaching thousands who prefer their information in prechewed pieces. The two-week 2021 Gaza war has been called the Tiktok Intifada. The hashtag #gazaunderattack had over 535 million views. The hashtag #pal- estine, 27 billion.[143]

Consider the following. In July 2024 Francesca Albanese claimed on Twitter that the Israelis had killed not 37,000 people in Gaza, the already-inflated number from the Gaza Ministry of Health, but rather 186,000. The figure came from phantom arithmetic in a letter published in the British medical journal The Lancet, which claimed to predict the discovery of additional deaths at a four-to-one ratio. Albanese’s post was seen over 607,000 times.[144] The 186,000 number was soon trumpeted by Aljazeera, The Guardian, The Nation, Middle East Eye, Democracy Now! and other such outlets.[145] Inter Press Service (which covers the UN) called it a “staggering” estimate, which “has resurrected accusa- tions of genocide,” as it had come from “one of the most prestigious peer-reviewed British medical journals.”[146]

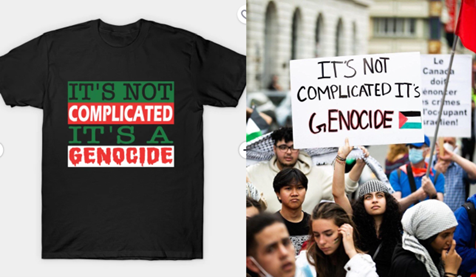

All of which leads us to the slogan in public demonstrations and on social media and numerous news platforms that seems to have emerged in early 2024: “It’s not complicated. It’s genocide.” Indeed, the connection between settler-colonial theory and genocide is not complicated because it avoids all complexity. “It’s not complicated” discourages all discussion of the Genocide Convention, case law in genocide trials, the efficacy of settler-colonial theory, and the entire history of the conflict including terror attacks, hijackings, failed peace negotiations, intifadas, suicide bombings, rocket launches, kidnappings, Iran, Hezbollah, Houthis, the Hamas Charter, and October 7 itself. In fact, anyone who raises these matters is engaging in deliberate confusion, smokescreens and lies and will quickly be denounced as an aider and abettor of genocide, a perpetrator themselves, precisely because, as the slogan has it, genocide is not complicated.

In conclusion, the widespread genocide accusation has further dele- gitimized Israel and indeed most Jews in ways that their opponents could only have dreamed of during events like the 2001 UN conference on racism in Durban, South Africa.[147] As for what lies ahead, the Gaza war will end, most Hamas leaders will be dead, the rebuilding of Gaza will begin, and hopefully, moderation may prevail. Meanwhile, arguments linking Israel, settler-colonialism, and genocide must be rigorously contested in the hope that reason and a more sober sense of reality can take precedence.

clare-murphy/white-house-denies-genocide-unfolding-gaza (accessed February 2025); Raz Segal and Penny Green, “Intent in the Genocide Case Against Israel is Not Hard to Prove,” Aljazeera, January 14, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2024/1/14/ intent-in-the-genocide-case-against-israel-is-not-hard-to-prove (accessed February 2025).

Omer Bartov, “What I Believe as a Historian of Genocide, The New York Times, November 20, 2023.

International Court of Justice, The Hague, Public Sitting, 11 January 2024, Verbatim Record, 33–34, https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/192/192-20240111-ora-01-00-bi.pdf (accessed February 2025).

‘The Jerusalem Declaration,’” Fathom Journal, April 2021, https://fathomjournal.org/fathom- long-read-accommodating-the-new-antisemitism-a-critique-of-the-jerusalem-declaration/org/fathom-long-read-accommodating-the-new-antisemitism-a-critique-of-the-jerusalem-declaration/; Jeffrey Herf, “IHRA and JDA: Examining Definitions of Antisemtism in 2021,” Fathom Journal, April 2021, https://fathomjournal.org/ ihra-and-jda-examining-definitions-of-antisemitism-in-2021/

https://www.globalissues.org/news/2024/07/10/37158#%3A~%3Atext%3DUNITED%20NATIONS%2C%20Jul%2010%20%28IPS%29%20-%20An%20overwhelmingly%2Cand%20Hamas%2C%20with%20no%20signs%20of%20a%20cease-fire. (accessed February, 2025).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Norman J.W. Goda is the Norman and Irma Braman Professor of Holocaust Studies at the University of Florida. He is the author of Tomorrow the World: Hitler, Northwest Africa, and the Path toward America (1998); Tales from Spandau: Nazi Criminals and the Cold War (2007); The Holocaust: Europe, the World, and the Jews (2nd ed, 2022). He has co-authored, with Richard Breitman, US Intelligence and the Nazis (2005) and Hitler's Shadow: Nazi War Criminals, US Intelligence, and the Cold War (2010). He has edited three volumes of his international essays titled Jewish Histories of the Holocaust: Transnational Perspectives (2014); Rethinking Holocaust Justice: Essays Across Disciplines (2018); and with Edward Kissi, Outside Looking in: The World Universalizes the Holocaust (2026). He served as lead editor on To the Gates of Jerusalem: The Diaries and Papers of James G. McDonald, 1945-1947 (2014), which concerns Holocaust refugees and the question of Palestine in those years, and Envoy to the Promised Land: The Diaries and Papers of James G. McDonald, 1948-1951 (2017) which concerns McDonald's work as the first US ambassador to Israel and the initial years of the new state.