Download PDF Back to Research Paper Series

| Suggested Citation: Grayson, Mara Lee. 2024. "The Racialization of American Jews and Antisemitism on College Campuses." ISCA Research Paper 2024-2. |

Download PDF Back to Research Paper Series

| Suggested Citation: Grayson, Mara Lee. 2024. "The Racialization of American Jews and Antisemitism on College Campuses." ISCA Research Paper 2024-2. |

by Mara Lee Grayson

September 2024

When I began researching rhetorics of antisemitism in academia, I was a faculty member in an English department, approa- ching tenure, and trying to make sense of my experiences as a Jewish woman teacher and scholar whose research focused on racism in education. I took on this new research project for a rather selfish reason: I wondered what other Jewish scholars had experienced; that is, I wondered if I was alone in my loneliness. I found out almost as soon as I began inter- views that I wasn’t: like me, the scholars I interviewed had experienced antisemitism, both coded and overt, and generally felt that Jewish ideas and the concerns of Jewish teachers and students were unacknowledged, including in spaces ostensibly dedicated to equity and social justice. Many of the educators I interviewed recalled that their concerns had been dismissed by colleagues for the same reason: According to those colleagues, they were white.

My book detailing this research and exploring the racialized dynamics of contemporary antisemitism, Antisemitism and the White Supremacist Imaginary: Conflations and Contradictions in Composition and Rhetoric, was published a few months before the antisemitic terror attack on Israel on October 7th. In the months since then, the rhetoric that has accompanied the rise in antisemitic violence, harassment, and vandalization, particularly on North American college campuses, has only cemented my position that to counter contemporary antisemitism, we must understand the contradictions and paradoxes that characterize the racialization of Jewish people today.

In the United States in particular, Jews are simultaneously con- structed as white by some (such as activists who apply a Black/white binary to both Jewish identity and to the ongoing conflict in Israel/ Palestine) and nonwhite by others (such as white supremacists)[1]. At the same time, Jews are also conceptualized as outside the Black/white binary that remains central to contemporary constructions of race (such as when Jewishness is framed as religion only and the racialized nature of antisemitism). I have argued that these contradictions are both inten- tional and necessary to both the maintenance and obscuration of con- temporary American antisemitism[2].

If the paradoxes and contradictions that characterize Jewish racial- ization and contemporary antisemitism are of scholarly significance (I believe they are), arguably more important are their tangible, real-world, everyday impacts on the lived experiences of Jews. For decades, researchers in psychology, sociology, education, student affairs, and public administration, among other disciplines, have documented the over- sight of Jewish perspectives and the limited awareness of antisemitism in their fields, as well as the deleterious impacts of those gaps on Jews, especially young Jews[3]. Antisemitic attitudes and incidents, already on a steady rise around the world, increased exponentially after October 7th. College campuses have long been significant loci of antisemitic senti- ment and activity, and in the past year, Jewish college students across the country have been assaulted, harassed, prevented from entering university buildings, subjected to targeted propaganda drawing on medieval and Holocaust era antisemitic tropes, labeled genocidal murderers and white colonizers, and witnessed their cultural symbols and ideologies be appropriated and maligned by peers, professors, and politicians. To those of us with a personal or professional stake in what happens to Jews, the antisemitism of the current climate, especially on college campuses, is so obvious that it seems impossible to overlook. Yet we also know that many people do overlook, minimize, or intentionally obscure the harms being perpetrated against Jews, in large part because Jew-hatred, a bigotry that is both religious and racial, doesn’t fit easily within a social justice framework that sees oppression in terms of a color binary and conflates Jews with whiteness.

* * *

The ill fit of these frameworks for understanding Jewishness and anti- semitism is evident in the experiences of Jews, like Rebecca and Cindy, two Jewish women I interviewed when they were doctoral students.

When Rebecca moved from Brooklyn, New York to the Southwest to begin a doctoral program at a major research university, she quickly realized she was seen as, in her words, “an anomaly.” She was regularly questioned by classmates (and even faculty members) about her Kosher diet and her observance of Shabbat. Her professors and colleagues often failed to take those practices into account, scheduling her for Saturday presentations and providing no Kosher food options at events. When Rebecca requested a schedule change for a disciplinary conference, organizers refused to provide the accommodation. Another time, while visiting for a conference on campus, a scholar who had recently gradu- ated from Rebecca’s program repeatedly—and apropos of nothing— asked Rebecca if she was allowed to use money on her Sabbath, invoking a classic antisemitic trope that associates Jews with money.

While many of Rebecca’s experiences fall into the category defined by multicultural psychologists as microaggressions, or the frequent slights against members of minority groups that go unnoticed by others, some of her experiences have been far more overt and aggressive, even vio- lent. More than once while she was out with her husband in their college town, strangers shouted slurs like kike and threw objects at them. Her husband, Rebecca noted, wears a kippah and has features stereotypically associated with Jewish men, including a prominent nose and a dark beard. Orthodox Jews like her and her husband, who may be more visibly and identifiably Jewish, are the likeliest to be targeted by antisemitic hate crimes[4].

Yet when Rebecca joined an informal support group for marginalized students and faculty members in the wake of hateful political rhetoric in 2017, the year white supremacist and neo-Nazi hate groups marched through Charlottesville shouting “Jews will not replace us,” the profes- sor who had organized the group strongly and publicly admonished Rebecca for using the pronoun “we” when referring to populations targeted by hate speech. The professor, it seemed, could not see Jews as marginalized or targeted by hateful political rhetoric.

When I spoke with Rebecca in 2021, she told me that she still didn’t have a place in her program to talk about the antisemitism she experienced: “I don’t feel like I have a community.”

Cindy had a somewhat different experience as a doctoral student at a major research university in the Northeast. She talked openly about Jewishness in the courses she taught, sharing how her Jewish identity and community impacted her approach to reading, writing, and language. The very first time she did so, a Jewish student thanked her. That student, she learned, hadn’t previously reflected upon, let alone talked about, her Jewish identity in school.

Outside of Cindy’s classroom, it was a different story. When two antiracism experts that Cindy admired led a workshop for students in her program, another Jewish graduate student asked how discussions of antisemitism might be incorporated into equity and inclusion work. Neither of the workshop leaders answered the question. When Cindy repeated the question, she was, in her words, “silenced.”

Another time, a colleague who had been assigned to teach a course on diversity approached Cindy to ask her how to address antisemitism. The colleague told Cindy that a student in the diversity class “was com- plaining about antisemitism” and she didn’t know what to do because antisemitism wasn’t part of the curriculum. Cindy wasn’t upset with her colleague, who, she explained, knew little about Jewish identity or anti-semitism, and “was following protocol.” What bothered Cindy was that the protocol simply didn’t include Jews.

“Unless you’re Jewish,” she told me, “nobody cares.”

Like Rebecca, Cindy experienced both coded and overt antisemitism, most often in the form of hate speech. However, unlike Rebecca, who was told that her voice didn’t belong in a conversation about hate speech, Cindy found that, as long as she mentioned that her family is from Morocco and her father has dark skin, she wasn’t shut down when she spoke of her experiences as a Jewish woman in such conversations. Even with lighter skin herself, her North African heritage and her father’s skin color enabled her to be seen as someone who could speak to a nonwhite experience. In conversations about identity or discrimination, she could “enter the conversation there.” Cindy called this approach “a crutch.” If it made those around her feel like she had “a stronger reason” to talk about marginalization, it didn’t feel like the right reason: “I have to rely on that,” she said. “I wish I didn’t have to just rely on that to talk about being Jewish.”

Both Rebecca and Cindy are Jewish women. Both have skin that could mark them as white. Both are descendants of refugees. Both have experienced antisemitism. Both have generally felt excluded from conversations about diversity and inclusion. Rebecca is arguably more visibly Jewish, due to the clothing she wears as an Orthodox woman, and statistically she was more of a minority in a Southwestern college town with a tiny Jewish population than Cindy was in a major Northeastern city with an established Jewish community. Yet when Cindy talked about being marginalized as a Jewish woman, she was heard—as long as she mentioned her father’s skin color and her family from North Africa.

* * *

Despite the limitations of the persistent racial binary of the United States, skin color remains the defining marker of marginalization, including or perhaps especially in academia. Jewish identities—and antisemitic narratives that impact how American Jews are perceived— confound the understandings of race and racism that remain central to equity work and identity politics today.

“People don’t know what to do with Jewishness,” Rebecca told me in 2021. When she recalled being subjected to classmates’ assessments of her racial identity and their musings about whether or not she was white, I thought of my own experience being subjected to such a debate in a graduate class on diversity in education—a debate, it is worth noting, that neither included nor invited my perspective. What’s more, as was the case with the diversity class Cindy mentioned, there wasn’t anything about Jewish identity or antisemitism in the curriculum in that class; the debate about whiteness had only begun because I mentioned something about my experiences.

In academic life, complex situations are often embraced as puzzles. Yet instead of unpacking the complexity of Jewish ethnoreligious identification, the vast majority of programs dedicated to the study of cultural identities simply ignore it. While the earliest iterations of multicultural education did include examinations of Jewish identity and antisemitism, initiatives in ethnic studies, multiculturalism, and what has come to be called “DEI work” (denoting “diversity, equity, and inclusion”) largely elide Jewishness and antisemitism[5].

Like other researchers of contemporary antisemitism, I believe that this exclusion, particularly in recent years, results in large part from dominant narratives of Jews as colonizers, rather than an indigenous population, in the Middle East, and the subsequent conflation of all Jews (both in Israel and around the world) with specific actions of the Israeli government. But in the United States and other parts of the western world, where pluralistic conceptions of multiculturalism have morphed into critical yet binary constructions of race and power, that narrative hinges on another conflation: the conflation of Jews with whiteness.

I’ve researched and written about racism and whiteness in education for many years[6]. I understand why people generally see even perceived whiteness as a disqualifying factor for inclusion in programs designed to support minority or minoritized peoples. Light skin confers certain privileges in a color-centric race-based hierarchy. Empirically, we known that people with light skin are stopped less frequently by police when driving, receive shorter prison sentences for similar crimes, and report feeling safer, including in educational settings, than people with dark skin[7].

Light skin and the benefits it may confer are often conflated with whiteness, a term used to denote the underlying ideological, cultural, and structural system that both comprises and informs dominant notions of normality and morality[8]. But that complex system is not a Jewish one, nor is it, as common parlance would have us believe, a “Judeo-Christian” one. The label “Judeo-Christian” obscures the distinctions between Judaism and Christianity, the historical oppression of Jews in the name of Christianity, and the secularized Christianity of contemporary North American countries, where holidays honoring the birth and death of Christ are celebrated culturally and commercially. (It is worth noting that Christmas is also a federal holiday in the United States, despite the legal separation between religion and state.)

In modern Europe, where contemporary notions of race originated, the idea of a white race was inextricable from Christian cultural identity. It is that deep connection between whiteness and Christianity that underlies both the white supremacist’s hatred of Jews and the sense of difference even light-skinned Jews experience in societies wherein they are believed to have white privilege. Indeed, research has repeatedly shown that Jews, despite being lumped into the same category of white- ness that has historically excluded them, do not share the beliefs or prac- tices of the dominant white culture[9].

For Jews, even those with light skin, skin color guarantees neither inclusion nor safety. Light skin did not ensure the safety of the 11 congregants murdered by a white supremacist at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue in 2018 or those murdered or maimed by a white supremacist at a synagogue in Poway, outside San Diego, in 2019. And, of course, light skin offers absolutely no benefits to those Jews who don’t have light skin at all.

In reality, the skin color of Jews varies widely. Most research shows that approximately 15 percent of American Jews identify as People of Color, and about half of Jews in Israel, where nearly half of Jews in the world reside today, have skin that would not afford them white privilege. A recent study showed that 42 percent of American Jews who identify as People of Color also identified as Ashkenazi10, or of recent Eastern or Central European descent, the Jewish population most readily associ- ated with whiteness. Even the Pew Research Center has admitted that the “amount of diversity in U.S. Jewish population varies depending on definition”[11].

Skin color variation does not negate racialization, the process by which a community and its members are categorized according to supposedly hereditary biological traits. Racialization suggests that a group of people are, by nature, different, and, often but not always, attempts to identify that difference through (supposed) phenotypical characteristics. Racial antisemitism suggests that Jews ought to be disliked or discriminated against not because they worship differently but because they are different. Contemporary understandings of racism in the United States are closely linked to appearance and color, meaning that, for antisemitism to be understood as racial, Jews must also be seen to look different.

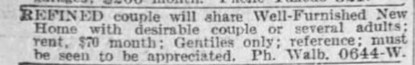

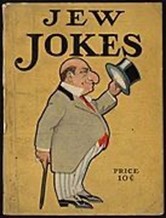

In the colonial United States, preceding the binary of Black and white were the labels “Christian” and “heathen.” The tiny Jewish population had religious freedom but experienced social discrimination, much of which was expressed in racialized terms. Increased Jewish immigration during the late 19th and early 20th centuries was met with systematic discrimination in areas of housing, employment, higher education, and social networking. Jewish workers, considered nonwhite, were excluded from labor unions and occupations like painting, printing, and carpentry[12]. University admissions offices employed race-based measures such as requesting applicants’ photographs to determine the Jewishness of potential students. Antisemitic propaganda that prevailed in popular culture frequently mirrored the racialized depictions of Jews common in Europe: Large, hooked noses, thick, protruding lips, and dark, kinky hair. This combination of systemic discrimination and racialization is racism by definition.

In efforts to find biological excuses for antisemitism, scholars of the late 19th and early 20th centuries repeatedly attempted to determine the phenotypical character of Jews within the Black-white binary that by then dominated racial politics, but they failed to fit Jewishness on either end. The consensus, if one can call it that, was that Jews weren’t white, but weren’t as nonwhite as Black or Native American people were.

Such in-between positioning was convenient for members of the non- Jewish majority. When white people needed the pretense of inclusion or to distinguish Black people as somehow being uniquely deserving targets of racism, Jews could be positioned as white. When white allies were needed in social justice movements, such as the tolerance cam- paigns by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, Jews were positioned as white. The flexibility of Jewish racialization operated in accordance with the uses of antisemitism: When white Christian society needed a scapegoat for societal changes or challenges, such as those that occurred in the wake of the Civil War, Jews became a nonwhite other who threatened the white, Christian, American way of life.

Jews increasingly occupied the nonwhite end of the racial binary in the United States and Europe in the years leading up to the Holocaust, which provides the most horrific example of the uses and outcomes of Jewish racialization to date. The long history of Jewish racialization lives on today, not only conceptually and rhetorically but also in the embodied experiences of many Jews.

When a stranger calls me a “hook-nosed Jew bitch,” that’s racialization. When non-Jewish actors wear large prosthetic noses to play Jewish characters whose noses looked nothing like those prosthetics, that’s racialization. When college students who are visibly Jewish (whether by clothing, jewelry, or physical features) are stopped on campus by protestors demanding they speak for or condemn the nation of Israel, that’s racialization. In each of the instances I have just described, Jewish individuals and groups have been racialized as Jewish. Racialization also helps to explain why the cartoon villain archetype is defined by a long nose, sharp chin, and dark eyes, why hair bleach and nose jobs have historically been means by which long-nosed Jewish women could more closely approximate western beauty ideals, and why the “Jewish nose” is still listed in some surgical textbooks as pathological and in need of correction.

These examples demonstrate the phenotypical character of Jewish racialization, but Jewish racialization is often biological but not visible. Research shows that nearly one in four Americans endorse anti-Jewish tropes, such as that Jews are dishonest, clannish, or disloyal to their country of residence[13]. These tropes essentialize Jewish people by suggesting that such characteristics are intrinsic to who Jews are, regardless of how Jews look. That type of racialization is confusing to those who see race purely through the lens of color.

Holocaust survivors continue to suffer psychological and physical impacts. Many American Jews today are the descendants of survivors or refugees from antisemitism somewhere, often only one or two generations ago: Rebecca, for example, is the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors; Cindy’s grandparents fled Morocco in the 1950s; and another student I interviewed is the child of a Jewish refugee from Egypt. My grandparents escaped pogroms in Russia. Our families weren’t targeted because of particular religious practices—they were targeted because they were Jews. The Jew-hatred that lives on in our bodies isn’t about reli- gion; it’s anti-Jewish racism. Yet, while research with survivors and families helped inform contemporary understandings of racial trauma, Jews are, seemingly inexplicably, excluded from many contemporary conversations about the lasting effects of systemic oppression and discrimination.

* * *

Despite historical and contemporary racialized discrimination and regardless of any individual Jewish person’s skin color, conceptually, American Jews today are also racialized as white. It is important to note that the presumption that Jews are white is a remarkably recent phenom- enon in Jewish—and, indeed, American—history, having arisen in the later decades of the 20th century, when Jewishness came to be framed as an ethnicity rather than a race. (A particular irony of this reconstruction today is the exclusion of Jewish Americans from the field of ethnic studies.[14]) Just like the racist 19th century pseudoscientists who mea- sured Jewish people’s heads in attempts to determine whether Jews were Black or white, late 20th century scholars of race and identity attempted to fit Jews on the white side of the racial binary. For example, in 1990, psychologist Janet Helms posited in her model of white identity development that Jews were “ethnic whites,” a framing that erases both the embodied experiences of dark-skinned Jews and the racialized nature of antisemitism.

Ironically, racialization as white today serves the same aims of anti- semitic exclusion and marginalization that racialization as Jewish once served. The racialization of Jews as white enables a professor, like Rebecca’s, to admonish a Jewish student for identifying herself among those impacted by discriminatory rhetoric at a time of heightened antisemitic rhetoric. That white racialization also enables the instructor of a class on diversity to, as Cindy’s colleague did, view a college student’s inquiry about antisemitism as a complaint rather than a legitimate concern. Jews, who make up approximately two percent of the population of the United States, are, year after year, the targets of the majority of hate crimes directed at a religious group[15], and are seen as a nonwhite race by white nationalists who publicly declare their intent to eradicate peoples of non- white races—yet in the context of cross-racial solidarity, Jews often are seen not as a minority but as representatives of white supremacy.

Perhaps in no context has this paradoxical dynamic played out more clearly than on college campuses since the October 7th attack on Israeli civilians by Hamas, a terrorist group that declares its genocidal antisem- itism in its own charter[16]. Visibly Jewish students (identified by clothing or phenotypical features) have been violently attacked by fellow students and outside activists on college campuses across the country. Jewish institutions have been vandalized. Some students have been warned by their parents to avoid displaying jewelry or clothing that marks them as Jewish—to, in other words, minimize the extent to which they can be racialized by appearance.

On the same college campuses, other students, as well as faculty members and entire academic departments, have publicly equated both Israel, a country, and Zionism, understood most basically as a belief in Jewish self-determination in the ancestral homeland, with racism and white supremacy. In other words, while Jewish students are racialized as Jewish and excluded from campus life because they are Jewish, Israel, the only Jewish nation in the world, is demonized as a white supremacist, settler colonial state, and Zionism, a complex Jewish ideology (or, perhaps more accurately, a collection of Jewish philosophies and ideologies), is maligned as a white supremacist, settler colonial political system.

Framing Zionism as racism is by no means a new tactic of antisemi- tism, but one that dates back to at least the 1960s, when it was the strategy of Soviet Union campaigns designed to delegitimize Israel and destabilize Israel’s democratic allies. This longstanding rhetorical strategy has had a significant impact on college students—and some faculty—in the United States[17], where education on Jewish identity and antisemitism are nearly nonexistent and where global geopolitics are framed, inaccurately and without context, through the same lens that has been used to make sense of American racism and police brutality.

Years before October 7, 2023, Jewish students were removed from or pushed out of student social organizations and student government positions at universities in the United States, including multiple Univer- sity of California campuses, after being labeled “Zionist,” which, they were told, made them racist. In 2018, pro-Palestine activists declared their mission to “make being Zionist uncomfortable on the NYU cam- pus;” the mission, activists clarified, wasn’t “against Judaism” but against racism[18]. In 2021, a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion student senator in USC’s graduate association posted on social media that she wished to “kill every motherfucking Zionist”[19].

These students’ understandings of inclusion and antiracism appar- ently not only allowed for but necessitated the exclusion of somewhere between 80 and 95 percent of American Jews and nearly all Israeli Jews (depending on how “Zionism” is defined). To some students, the murder of the majority of the world’s Jewish population was similarly justified. In such a climate, is it any wonder that when more than 1,200 innocent Israelis were killed, raped, tortured, and taken hostage by openly genocidal antisemites, so many students—and faculty—who believed them- selves to be advocates for social justice not only refused to condemn the violence but framed it as a justified act of resistance?

Jewish students on college campuses may find little empathy from or allyship among their peers, but the detriments of white racialization are not limited to matters of solidarity or belongingness. Many educational initiatives ostensibly designed to support racial and ethnic minorities are specifically geared toward minorities identified as under-represented (URMs). Because Jews are perceived as white and/or as “overrepresented” (a framing similar to the antisemitic logic used to justify enroll- ment quotas in the 1920s), they are not given access to these opportunities—regardless of minority status, experiences of marginalization, or economic need.

Historically, social discrimination against Jews has preceded and served to justify systemic economic and political discrimination, the likes of which we are increasingly witnessing, albeit in somewhat covert, coded ways, today. Consider, for example, incidents at and near the University of California, Berkeley, in April 2024: Just days after Erwin Chemerinsky, a Jewish professor and Dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law who has rarely spoken publicly about Israel became the subject of a racializing, antisemitic propaganda campaign that labeled him a “Zionist” and accused him of murdering Palestinian children, activists dis- rupted a dinner he and his wife, Catherine Fisk, a fellow professor, were hosting at their home. When the protestors refused to leave the private property despite numerous requests, Fisk attempted to grab a microphone from a protestor’s hand. The incident was recorded and posted to social media, where Chemerinsky and Fisk were labeled “violent white supremacists with fancy degrees” and accused of assault on a Muslim protestor.

The news media debriefing of the incident that followed, including Chemerinsky’s own response in The Atlantic, focused on the difference between public protest on a university campus and trespassing on pri- vate property and on the antisemitic trope of blood libel in the posters that initially targeted Chemerinsky. What few news reports and op-eds unpacked, however, was the dynamic of racialization that played out on social media as scholars and activists attempted to make meaning of the event through frameworks more familiar—and more useful—to them. Ignoring that the protestor, a woman in a hijab, occupied the private property of a Jewish man she had targeted and essentialized because he was Jewish, self-identified antiracists positioned the perpetrator as a racialized and gendered victim and the victim as a white supremacist. Through a binary worldview that sees light skin as the mark of an oppressor and darker skin as a sign of perpetual powerlessness, a brown- skinned student is far more easily seen as the victim than a light-skinned professor, even when that student is legally in the wrong.

Now-deleted post on X (formerly Twitter) by author and politician Saira Rao on April 10, 2024. Shared to Berkeley Tumblr. Credit: intersectionalpraxis. Direct link: White people on stolen land proclaiming something is theirs while assaulting a person who wants to stop an ongoing genocide... – @intersectionalpraxis on Tumblr

Instagram post by PeoplesCityCouncil, April 11, 2024.

The labels and accusations levied against Chemerinsky aren’t just misguided, reductive attempts to intellectualize a complex situation (though they are indeed misguided and reductive): Student and faculty activist groups also called for both professors to be fired. It is worth noting that the same student groups that distributed the antisemitic posters previously called, unsuccessfully, for a boycott of the event at Chemerinsky’s house; when the protestor who disrupted that event was asked to leave, her removal was labelled an act of racism and a reason for Chemerinsky’s firing. Thus, a Jewish man’s racialization as white served as a strategy by which antisemitism against him could be both justified and perpetuated.

The shift from racializing social propaganda to attempted economic discrimination can be seen in other professional arenas as well. Since October 7th, some publishing houses and literary journals have posted warnings on their submission pages that they do not publish work by “Zionists.” Jewish authors accused of being “Zionist” have seen their books blacklisted from bookstores and reading groups and have been subjected to organized “rating-bombing” on user review websites. Art museums have relocated or modified exhibits accused of sharing “Zionist” perspectives. The term “Zionist” has historically operated as met- onymic code for “Jew” and, regardless of some activists’ attempts to theoretically sever anti-Zionism from antisemitism, it operates similarly today, both rhetorically and politically. But it does so under the cover of white racialization, which, in a society struggling to reconcile its rela- tionship with white supremacy, makes it far more difficult to recognize.

* * *

White racialization may be very recognizable, however, to Jews who don’t have light skin, like the Latina Jewish Brooklyn College student who, during a lesson in her graduate program, was assigned to complete a worksheet about white identity development[20]. As a process, racializa- tion doesn’t require accuracy. That Jewish people are presumed to be white, even if individual Jews do not all look white or identify as white, and despite the fact that cultural whiteness does not reflect Jewish experience, is a manifestation of racialization itself.

The presumption of whiteness that enables the minimization of anti- semitism today also facilitates the minimization or erasure of historical antisemitism, even in its most virulent forms. In a strange sort of revisionist history, to some people, even our ancestors were white. Consider, for example, actress and talk show host Whoopi Goldberg’s comments on national television that the Holocaust wasn’t about race but about two groups of white people. Or the prevalent and decontextualized use of the term “Nazi” to denote a sort of generic fascist, thereby stripping Nazism and the Holocaust of their explicitly anti-Jewish character.

We see similar denials and attempts at redefinition among activists who seemingly wish to vindicate Hamas for acts of terrorism, despite the fact that Hamas, like the Nazis who numbered their victims and recorded the names of the Jews they murdered in concentration campus, documented and shared their actions with the world. Hamas’s charter and its leaders have openly declared their intentions to rid the world of Jewish people, intentions that are explicitly genocidal, racial, and racist. The Houthi flag declares in Arabic: “Death to America Death to Israel A Curse Upon the Jews.” Yet some activists, including university faculty members, claim that these internationally designated terrorist groups whose members have admitted to and reveled in the rape, torture, and murder of Jews aren’t terrorists but radicals, militants, or resistance fighters, and that their issue is with Zionism, not Jews. Jewish racializa- tion and the discounting of Jewish racialization both go hand-in-hand with antisemitism.

It is generally understood that ignoring or erasing the social, cultural, and rhetorical dynamics that have contributed to past atrocities makes it easier for those atrocities to happen again, for their enabling condi- tions and early manifestations go unidentified. Because the racialization of Jews and the racialized nature of antisemitism have been ignored or obscured, many people cannot recognize these insidious, paradoxical, and dangerous dynamics. Such dynamics should be of interest to those who study identity and inclusion, especially at a time when Jewish peo- ple, including students, are imploring their peers, professors, and elected officials to simply acknowledge Jewish suffering. It is time for educators and administrators who profess their dedication to diversity, equity, and inclusion, like Rebecca’s professor and Cindy’s colleague, to honestly and critically consider why the suffering of Jews continues to be over- looked. To their Jewish students, the reason is obvious.

[1] Baddiel, D. (2021). Jews don’t count: How identity politics failed one particular iden- tity. TLS/Harper Collins; and Schraub, D. (2019). White Jews: An intersectional AJS Review, 43(2), 379–407.

[2] Grayson, M. L. (2023). Antisemitism and the white supremacist imaginary: Confla- tions and contradictions in composition and rhetoric. Peter Lang.

[3] See Flasch, P. (2020). Antisemitism on college campuses: A phenomenological study of Jewish students’ lived experiences. Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism, 3(1), 59–69; Levine Daniel, J., Fyall, R., and Benenson, J. (2019). Talking about antisemitism in MPA classrooms and beyond. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 26(3), 313–335; and MacDonald-Dennis, C. (2006). Understanding anti-Semitism and its impact: A new framework for conceptualizing Jewish identity. Equity & Excellence in Education, 39, 267–278.

[4] Stack, L. (2020, February 17). ‘Most visible Jews’ fear being targets as anti-Sem- itism rises. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/17/nyregion/ hasidic-jewish-attacks.html

[5] See Langman, P. F. (1995). Including Jews in multiculturalism. Journal of Mul- ticultural Counseling and Development, 23(4); Robinson-Wood, T. (2016). The convergence of race, ethnicity, and gender: Multiple identities in counseling. Sage; and Rubin, I. (2017). Whiter shade of pale: Making the case for Jewish presence in the multicultural classroom. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 19(2), 131–145.

[6] See Grayson, M. L. (2018). Teaching racial literacy: Reflective practices for critical writing. Rowman & Littlefield; Grayson, M. L. (2022). Who is it really for?: Trigger warnings and the maintenance of the racial status quo. College Composition and Communication, 73(4), 693–721; Grayson, M. L. (2022). The trigger warning and the pathologizing white rhetoric of trauma-informed pedagogy. Rhetoric of Health and Medicine, 4(4), 413–445; and Tevis, , Nishi, N., & Grayson, M. L. (2023). The gendered transaction of whiteness: White women in educational spaces. Palgrave.

[7] See Pierson, E., Simoiu, C., Overgoor, J. et al. A large-scale analysis of racial dispar- ities in police stops across the United States. Nat Hum Behav 4, 736–745 (2020); Starr, Sonja B. “Racial Disparity in Federal Criminal Sentences.” M. M. Rehavi, co-author. J. Pol. Econ. 122, no. 6 (2014): 1320–54; and Viano, S., & Truong, N. (2022). Black, Indigenous, People of Color and Feelings of Safety in School: Decomposing Variation and Ecological Assets. AERA Open, 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584221138484.

[8] Tevis, T., Nishi, N., & Grayson, M. L. (2023). The gendered transaction of whiteness: White women in educational spaces.

[9] Abrams, C. M., & Armeni, K. (2023). The Lived Experiences of Anti-Semitism Encountered by Jewish Students on University Campuses: A Phenomenological American Journal of Qualitative Research, 7(3), 172–191. https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/13482.

[10] Belzer, T., Brundage, T., Calvetti, V., Gorsky, G., Kelman, A. Y., and Perez, D. (2021). Beyond the count: Perspectives and lived experiences of Jews of color. Jews of Color https://jewsofcolorinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/BEYONDTHECOUNT.FINAL_.8.12.21.pdf.

[11] Amount of diversity in U.S. Jewish population varies depending on definition. (2021, May 5). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/05/11/race-ethnicity-heritage-and-immigration-among-u-s-jews/pf_05-11-21_jewish-americans-09-3-png/.

[12] Brodkin, K. (1998). How Jews became white folk and what that says about race in Rutgers UP.

[13] Anti-Defamation League. (2024, February 29). Antisemitic Attitudes in America, https://www.adl.org/resources/report/antisemitic-attitudes-america-2024.

[14] For more on Jewish exclusion from ethnic studies curricula, see Rubin, D. I. (2023). ‘Liberated’ ethnic studies: Jews need not apply. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 47(3), 506–525.

[15] Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2023, October 16). Press release: FBI releases 2022 crime in the nation https://www.fbi.gov/news/press-releases/fbi-releases-2022-crime-in-the-nation-statistics.

[16] Hamas Covenant 1988. (1988, August 18). The covenant of the Islamic resistance The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History, and Diplomacy. Yale Law School. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/hamas.asp

[17] Tabarovsky, I. (2024, July 30). Zombie anti-Zionism. Tablet Magazine. https:// tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/zombie-anti-zionism

[18] Jackson, S. (2018, April 27). Two student protestors arrested at rave for Israel’s 70th birthday in WSP. Washington Square News. https://www.nyunews.com/2018/04/27/jvp-protesters-arrested-at-rave-for-israels-70th-birthday-in-wsp/.

[19] Gerber, (2021, December 14). Toxic atmosphere of hatred.’ USC faculty out- raged over response to student’s tweets. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-12-14/usc-faculty-open-letter-student-tweet

[20] Redden, E. (2022, February 7). OCR opens inquiry into Brooklyn College anti- Semitism charges. Inside Higher Ed. The instructor had apparently never learned that there are indeed models of Jewish identity development that might have been more accurate. See, for example, MacDonald-Dennis, 2006.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Mara Lee Grayson is the author or editor of five books, including Antisemitism and the White Supremacist Imaginary: Conflations and Contradictions in Composition and Rhetoric (Peter Lang, 2023) and Challenging Antisemitism: Lessons from Literacy Classrooms (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023, co-edited with Judith Chriqui Benchimol). Grayson is founder and chair of the Jewish Caucus of the Conference on College Composition and Communication and chair of the Jewish Caucus of the National Council of Teachers of English. She holds a PhD in English Education from Columbia University and an MFA in Creative Writing from the City College of New York. Previously a tenured faculty member in the California State University system, she now works as the Director of Content Development for the Campus Climate Initiative at Hillel International. She is currently writing a book about the rhetorical constructions of disability and trauma in news media narratives of a Jewish man’s traumatic brain injury.