Download PDF Back to Research Paper Series

| Suggested Citation: Nelson, Cary. 2024. "The Future of Campus Antisemitism After October 7th." ISCA Research Paper 2024-1. |

Download PDF Back to Research Paper Series

| Suggested Citation: Nelson, Cary. 2024. "The Future of Campus Antisemitism After October 7th." ISCA Research Paper 2024-1. |

by Cary R. Nelson

September 2024

If we want to estimate the probable future of campus antisemitism—something we very much need to do if we are to prepare for what is certainly going to be a long-term struggle to combat it—we need to combine knowledge of antisemitism’s history with reflection on what has changed since the October 7 terrorist assault on Israel. We need as well to begin asking what we can learn from the nationwide campus “Gaza Solidarity Encampments” of Spring 2024. Combining these perspectives will lead both to some predictions about the future and to suggested strategies for action.

I should begin with some uncomfortable facts. We confront a simultaneous antisemitic rupture across multiple domains: in our assumptions about Israeli security and the reliability of Israeli intelligence estimates; over the physical threats Israelis will confront going forward; in our sense of the probable limits of unchecked human violence; over the status of Jews in the diaspora; regarding the future of a Jewish homeland; over the depth of incipient antisemitism hiding in our own backyards; in the character of antisemitism in our schools and universities; over the presence of evil throughout the world.

Because October 7 was all that and more, it is not surprising that some have simply retreated into the past. It is not uncommon to encounter Jews testing their confidence in prognostication: “this too shall pass”; before long, we will return to a “normal” level of hatred and malice. Of course normality in the United States was already categorically disrupted by the Pittsburgh and Poway murders. Expectations were already at least intermittently on edge, poised for something equivalent or worse, it’s unlikely that we will not be returning to the familiar abnormality that preceded October 7.

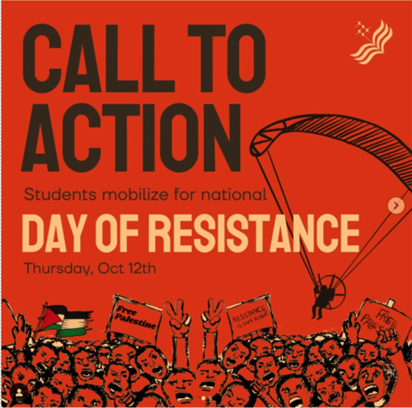

As many have observed, the flood of campus antisemitism arrived not in response to Israel’s declaration of war following Hamas’ attacks nor even in reaction to the IDF’s first bombing runs in Gaza. It came as a form of symbolic participation in the Hamas pogrom itself. As Dave Rich observes, as early as the 1982 Lebanon War, anger at Israel was displaced onto Jews everywhere, but it came in response to images of people dying in Israeli raids. This time, counter-intuitively, “it was the murder of 1,200 people in southern Israel, and the seizing of around 250 hostages, that triggered this outburst of anti-Jewish hatred.” [1] That is a watershed development in the normalization of antisemitism. It will not now disappear.

Meanwhile, heightened anxiety has to be grounded in impossible knowledge. Hamas’s conduct on 10/7 was fundamentally impossible to understand. The intricate, obscene, intimate brutality, sustained for hours, cannot really be registered in detail. It resembles an endless horror movie more than a series of believable crimes. So we retreat not into denial but into nonrecognition. We cannot remain face to face with the carnage of that day. We cannot hold the violence in our minds as an object of analysis and understanding. And yet we must try—because the intolerable facts of the massacre are now compounded by the determination of Hamas apologists on North American campuses and elsewhere to deny the reality of what took place, despite the substantial photographic documentation disseminated by the terrorists themselves. In an intolerable outcome, the contempt for Jewish women displayed by the terrorists who raped and mutilated their victims is replicated by Judith Butler and others who cast doubt on their crimes.

I thus feel a moral responsibility to approximate at least a glimpse of some of what the victims experienced, though, again, it is almost impossible to put one’s self in their place. Fear for themselves and family members, efforts at self-defense, surprise and shock, anger, excruciating pain, disbelief, often intermixed, place the fullness of their experience outside complete comprehension. And these descriptive categories themselves are too familiar, too cliched, to be adequate. Nor are the range of personal experiences interchangeable. A Jewish family under attack in its safe room, twenty Israelis crowded into a roadside shelter, a lightly armed kibbutz defender trying to block access by a murder squad and about to be overwhelmed, a child trying to process a nightmare attack turned real, parents lying on top of their children hoping that they would be shot and their children spared, concert goers gunned down in their cars, IDF soldiers unexpectedly under attack by a superior force, a civilian successfully hiding from the murder squads hearing another victim being tortured, a woman in a field undergoing the most primal sexual assault imaginable: these experiences are at once unitary, collectively designated as 10/7, and unique. The myriad horrors of a day and more, altogether monstrous and immoral on their own, known and unknown alike, combine to form a totality that we can only name clumsily and inadequately.

I always told my Holocaust poetry students that no matter how much you read, no matter how many films you watch, you will not actually approximate, no less enter, the experiential worlds of those in Auschwitz or the other death camps. If you visit camps and see the physical settings it helps bring the horror closer. But a wide gulf between us and that time persists nonetheless. If you visit the room below ground in Buchenwald with the ovens intact, see the slide from the outside that Jews were flung down, and the hooks below on which they were hung, the mind peoples the space with Jewish victims. And yet whatever they experienced remains unavailable. The dedication of the SS guards is even more incomprehensible.

And if you could experience the camps as an actual inmate, believing that you were in that nightmare world from which the only release was death, you wouldn’t choose to live that way even for a day. But imagining you could enter that world for a day itself entails a misconception. You would not cross the gulf unless you believed the day would never end. I do not think the inner world of the Hamas terrorists of 10/7 is approachable either. No political analysis of indoctrination, no explanation of amphetamine supplements, no historical context for hopelessness or anger, gives access to whatever enabled Hamas terrorists to sustain that intricate, intimate savagery for hours.

The Israelis underestimated what Hamas was capable of. We—all of us in the West—underestimated the depth of antisemitism lying in wait in our cities and on our campuses, among our students, our neighbors, and our faculty peers. Each of the wars with Hamas established a new floor for antisemitism, a new minimum antisemitism of substance and practice that would not recede when the war ended. Of course we have no sure idea of when the 2023/24 war will end or what its political ramifications will be throughout the world. In North America, it will be bad enough if it continues through this summer’s political conventions. Substantially worse if it persists through the November elections. But the odds are that the IDF will have some presence in Gaza into the fall and that people will still be dying there. We cannot know to what degree that will sustain antizionist activism, but we must be prepared for the possibility. At the very minimum, as Columbia’s David Schizer argues in a report by Abigail Shrier, that means universities must be better prepared to guarantee fair adjudication and punishment for violations of their rules. [2]

Many, though not all, of the campus encampments had faded away or been forcibly dismantled by late May, with protestors turning their attention to opportunities for making their presence known at graduation ceremonies. But SJP and FJP will work to restart some antisemitic activism when students return in the fall. Meanwhile, the new base for antisemitic antizionism is this: hatred. Neither a political analysis nor a political proposal. Hatred. That is what our students, staff, and faculty will face going forward.

With hatred replacing politics at center stage, we are entering a newly intensified emotional phase of campus conflict. It is grounded in the recognized psychology of othering and casting out of an enemy group. To be othered as a student or faculty member means no longer feeling welcome on your own campus. You are no longer a fit subject of empathy. You are reborn as Ruth amid the alien corn.

One consequence of Jewish faculty members being shunned for their Zionism is that they sometimes decide the career they have devoted their lives to is no longer worth the ignorant, self-righteous antisemitism they face from their colleagues day after day. There are seven people on the executive committee of my university’s new organization Faculty for Academic Freedom & Against Antisemitism. One colleague from the University of Illinois Chicago and one from the Champaign-Urbana campus have decided to take early retirement rather than persist in a hostile environment. [3] Both are accomplished senior scholars and teachers. Both are Jewish women. Both are more than capable of standing up for themselves, but they eventually found being unwelcome was not the condition in which they wanted to spend the rest of their careers.

The withdrawal of empathy they faced has broad unsettling effects on the remnants of dialogue for everyone. Rather than trying to win a debate, opposing camps primarily struggle for power over the other. The base level of antizionism is now primarily emotional. That hardly serves as a good model for a university education.

I do not believe the campus hatred for Israel will dissipate or decline any time soon. It is fundamental to a world in which antizionism and antisemitism have substantially merged. Post-10/7, hatred for Israel no longer has to be justified or rationalized on campus. The belief that all Jews are complicit in Israel’s purported crimes will be commonplace in antizionist advocacy. Jews who want to fit in with progressive groups will be required to condemn their own national heritage and millennia of ancestral ties to Israel.

The hate that flooded across American campuses within hours of the Hamas assault would not have been possible had it not been waiting in reserve. Without that assumption it is difficult to explain the counter-intuitive phenomenon of an unprecedented assault on Israelis prompting a surge of antisemitism. Hatred for victims of merciless, inhumane violence is not to be expected. For the campus left, that reaction may have been facilitated by outrage that Israelis, the left’s official oppressor group, were suddenly positioned as victims. Pure hatred helps deny that transformation. The October pogrom was a personal affront for some on the left; it falsified Israelis, turning them into something antizionists certainly know they are not, victims. Just as we did not imagine Hamas to be militarily capable of organizing and carrying out the October assault or of harboring sufficient hatred to fuel face-to-face butchery and rape, we did not understand the depth of latent anti-Israel passion in our students and colleagues. Now that it has found expression, it will not soon pass.

That means that students, faculty, and staff whose affinity for Israel partly shapes their identities are going to face increased pressure to disavow the relationship, effectively breaking with themselves. Most undergraduate students are at a vulnerable age when they are in the process of identity formation and consolidation. Zionist students in antisemitic campus settings will suffer assaults on their emerging identities. Indeed, with identity politics now dominating many campus disputes, we need to realize that assaulting Jewish student identities during their vulnerable, impressionable years is a primary goal for Israel’s opponents. It often replaces political disagreements over Israeli policy. Virulent attacks on Israel now serve simultaneously as attacks on the Jews in the room. SJP and FJP leaders are well aware that Israel itself is partly a sideshow, an excuse for attacks on Jewish identity, for global Jihad. After SJP/FJP encouraged their members to deface or tear down posters of kidnapped Israelis, those Jews who identify with Israel and witnessed the act or saw the remaining paper shards felt personally assaulted.

Students in programs with majority Zionist faculty and student membership may be able to withstand these psychological assaults but many others will find the level of psychological safety necessary to do their work difficult to sustain. Universities are not in the business of providing intellectual safety. Intellectual challenges are essential to education, and they are protected by academic freedom. But a sense of psychological safety is necessary if students are to believe they can express their views and debate the strengths and weaknesses of those views without being personally denounced or discriminated against. There is considerable research about the importance of psychological safety to learning, but many faculty members are unfamiliar with the concept and will persist in willfully ignoring the distinction.

The new campus hatred persuades students and faculty that discrimination against Zionists in their community is morally virtuous. That sentiment has been in limited evidence for several years. It will likely escalate in tandem with political antizionism now and may become majority motivation in some quarters. It is already undermining psychological security on a number of campuses. Departments that have adopted official policies of antizionism are virtually guaranteed to be personally hostile environments for Jewish students, faculty, and staff members.

For now, campus concern over Gaza will continue to be a trigger for aggressive treatment of Jewish students. How the war will be seen five or ten years later will depend largely on whether it makes space for a better political and economic future for Gaza, something that I believe requires the elimination of Hamas as a functioning political and military force. Only time under better conditions, however, can diminish the appeal of Hamas’s ideology itself. Meanwhile, the antizionist movement has been newly energized. Those who see it as their defining political cause, as central to their identity, will not give up now. Christianity historically defined itself in opposition to Judaism. So too does the left increasingly substitute opposition to Israel for its traditional affirmative commitments.

There is an alternative. One can maintain the commitments to egalitarianism and to fighting injustice without collapsing all the forces combatting those goals into a single demonized and imaginary Jewish entity. For Christianity, Judaism was fantasized as everything aligned against a merciful and loving god. Now, for the antizionist left, it is the Jewish state standing in the way of worldwide liberation. In the destructive dynamic that ensues, aggression against the imaginary opponent substitutes for the need to work toward realization of the group’s affirmative goals. The group is defined by simplistically declaring what it is not. And the actual impediments to progress are thereby obscured by collective conspiratorial hatred. As Mitchell Cohen observes in the wake of the Hamas pogrom in an April 2024 interview in Fathom, “it was always possible to advocate leftwing ideas like social and economic egalitarianism, without making excuses for murderers who declare themselves liberators.” He adds that it is “imperative to distinguish between an insistence that social and economic rights must come with political rights and a fantasy that makes oppressed people one big conceptual and global blur—an intellectual blur that mystifies the actual suffering of human beings and its causes.” [4]

That dynamic has not only further hardened in place but actually worsened after each conflict with Hamas. Each of Israel’s wars with Hamas has been met with a significant escalation of campus anti-Zionist rhetoric and sometimes with new and more aggressive actions as well. There have been four previous major hostilities between Israel and Hamas: in 2008–2009, 2012, 2014, and 2021. The year after the 2012 war we saw our first academic disciplines declare war on Israeli universities through their disciplinary associations, with American Studies and other associations for the first time endorsing the movement to boycott them. Those actions gained credibility for the campus-based boycott movement. The year after 2014 saw additional disciplines, including women’s studies, join the trend, while others continued pitched rhetorical battles among the competing constituencies. The 2021 war saw campus antizionists gather their forces more rapidly as academic departments for the first time adopted antizionism as their official policy. After the 2021 war it became increasingly common for Zionists to be denied membership in progressive student groups. In 2023 and 2024 we saw antisemitism drop the mask of antizionism, with Jew hatred and Israel hatred becoming clearly interchangeable for perhaps the first time. Antizionism and antisemitism had fused, making the question of when antizionism crosses a line into antisemitism irrelevant. Mass demonstrations against Israel for the first time populated campuses and communities alike, and physical violence was added to the threats Jewish students had to confront. The large demonstrations alone, shocking in their size, their performative intensity, and the rapidity with which they erupted and spread, demonstrated that antizionist antisemitism had entered a new era.

Once a new tactic enters the repertoire of campus antizionism, as with these examples, it becomes part of the established norm for protests and hostile action. Once departmental statements were issued for the first time in 2021, they began to drive department practices while also laying in waiting for expanded use when the occasion arose. This may be the most serious challenge campuses face—the corrosive, blatantly antisemitic impact of those academic departments that have declared themselves officially opposed to Zionism. My campus’ academic senate drafted a well-reasoned policy detailing why departmental statements on controversial political topics are ill-advised and likely to do harm. Such departmental statements discourage minority opinion, alienate those with competing opinions, coerce conformity from vulnerable faculty, students, and staff, and officially align all department functions with a political mission. They lead to litmus tests in hiring and recruitment. Tenured faculty can abuse their secure financial position to silence untenured and non-tenured faculty. I assume the authors of the senate policy imagined it would have some effect on a department in the grips of a political passion, with its faculty convinced of their moral righteousness and ready to prove they are on the right side of history. For all the influence it had the senate might just as well have written the policy in the local language of a galaxy far far away. While it mounts what appears to be a compromise, discouraging departmental politicization but preserving a misguided understanding of academic freedom, it leaves the freedom to comprehensively politicize intact. I am equally opposed to politicization that does and does not have my sympathy. What is needed is a firm policy prohibiting all departmental political statements. I propose one in my new book Hate Speech and Academic Freedom.

Harvard has tried to be more clear, but it still falls short of definitive prohibition for units outside the central administration. The Harvard administration and the governing corporation endorsed a committee report noting that by “issuing official statements of empathy, the university runs the risk of appearing to care more about some places and events than others” a warning that applies to all the department statements identifying with Palestinians but ignoring or minimizing Israelis. Best, it adds, for the university and its “component parts,” therefore, “not to issue official statements of empathy,” including “departments acting collectively.” [5] Such programs should not issue declarations “beyond their domain expertise, and they should not extend their zone of expertise unreasonably.” They mean that anthropologists are expert in anthropology, not in the political ambitions of all the wretched of the earth, and that gender and women’s studies scholars are not authorities on every territorial dispute cast as a human rights issue. But of course far too many anthropologists and gender studies scholars would beg to differ.

Predictably, then, we have seen many more such antizionist statements in 2023 and 2024, with more departments and disciplines joining in. Antizionist rhetoric and accusation can also take a different route, spreading gradually over a period of years, then exploding in use in response to new circumstances. Accusations of Israeli apartheid increased gradually over many years until they received a boost from 2021 and 2022 reports by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. Appearing in the wake of the 2021 war, these reports helped fuel a decisive normalization of the apartheid accusation, despite the fact that Palestinians serve as lawmakers in the Israeli parliament, as judges, doctors, and teachers, serving as well in the IDF. Accusations of Israeli genocide against Palestinians became gradually more common until they became omnipresent in response to Hamas’s flawed casualty numbers in 2023 and 2024. I have found that each war with Hamas establishes a new more aggressive floor for antizionism. Thus the question is: what new floor do we face in 2024 and beyond?

The aggressive group disruption of Zionist events on many campuses has now apparently become normalized. Participants are more willing to abridge academic freedom. Small scale violence and the threat of something more have increased. Too often, administrative cowardice means that sanctions for such actions remain out of reach. Columbia University banned Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), then turned the other way when the group continued to organize illegal demonstrations. Administrators like to take strong moral and political stands, as they did with the George Floyd murder, but only when everyone agrees with them. Not so much when campus opinion is polarized and responsible action requires courage and will come with political conflict and a personal price for those in charge.

Meanwhile the chants continue, with new variations introduced to demonstrate the irrepressible creativity of the participants. On the Columbia campus they called out “Disclose! Divest! We will not stop! We will not rest!,” “Oh Al-Qassam [Brigades], you make us proud, kill another soldier now!,” “One, two, three, four, Israel will be no more!,” “Five Six Seven Eight, Israel is a terrorist state,” “Israel will fall! Brick by brick, wall by wall!,” “Red, black, green, and white, we support Hamas’ fight!,” “Hamas we love you. We support your rockets too!,” “It is right to rebel, Al-Qassam, give them hell!,” and “From the water to the water, Palestine is Arab!” Students for Justice in Palestine gathered to lead chants wearing keffiyehs, displaying Hamas symbols, and teaching people to chant “Death to Israel,” “Death to America,” and “Death to the Jews” in Farsi and Arabic. Some chants were focused on eliminating Israel. Others sought to cleanse the campus of its Jewish undesirables.

The most time-honored chant “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” was invoked almost everywhere. Those who insist it has no eliminationist implications, no implication Palestinians will be free of Israelis and control the land, were more challenged after Hamas launched a genocidal pogrom intended to reach from the sea to the river. Michigan United States House of Representatives member Rashida Tlaib claims she means the slogan to be a call for peace and coexistence. Whether she is hypocritical or deluded is difficult to say, but a lone speaker in any case cannot successfully assert an alternative meaning for a slogan chanted by thousands of others.

Speaking from Qatar, Hamas leader and former politburo chair Khaled Mashal was very clear about where the terrorist group stands on the slogan in a January 2024 interview with Kuwaiti podcaster Amar Taki. “From the river to the sea” is an explicit call for Hamas dominance throughout, from east to west and north to south, “Hanikra to Eilat.” Any less totalizing reference, he adds, is merely a temporary political deception. [6] It is thus at best ignorant and pathetic for an American student to announce the slogan can usher in a utopia of peaceful coexistence.

But some alternative meanings are clearly disingenuous. When those issuing calls to “globalize the intifada” or chanting “There is only one solution, intifada revolution!” are pressed to realize those are demands for lethal violence they simply dissemble if they are among the few who know at least a little of the relevant history: “We only mean the first, not the second intifada,” whose signature events were the suicide bombings that killed civilians indiscriminately. Of course the chants cannot escape invoking the core legacy of suicide bombings. That is the one message delivered to Israelis and Jews everywhere.

Perhaps a degree of realpolitik dictated the substitution of “Arab” for “free” in some versions of the chant. Paul Berman in a Washington Post essay writes that “some people will claim to hear nothing more than a call for human rights for Palestinians. The students, some of them, might even half-deceive themselves on this matter ...The slogan promises eradication. It is an exciting slogan because it is transgressive, which is why the students love to chant it. And it is doubly shocking to see how many people rush to excuse the students without even pausing to remark on the horror embedded in the chants.” [7] Even Peter Beinart admits “slogans like ‘Palestine will be free from the river to the sea” in fact “don’t acknowledge a place for Israeli Jews in that vision,” though his phrase deliberately understates the malice at issue. [8] At least in English, “water to water” has a nonspecific global reach; from water to water across the four corners of the earth Israelis and their Jewish allies will be cast out, unwelcome. Attached to Hamas, again, it suggests global Jihad.

In the grip of a group emotion, the chant seems like it can make it so. It has magical power. But in reality, not. As Zadie Smith writes, “The more than seven million Jewish human beings who live in the gap between the river and the sea will not simply vanish because you think that they should. All of that is just rhetoric. Words. Cathartic to chant, perhaps, but essentially meaningless.” It is “Language euphemized, instrumentalized, and abused, put to work for your cause and only for your cause, so that it does exactly and only what you want it to do.” [9] Smith is correct to regard the chanting’s immediate political efficacy with contempt. What it may lead to long-term if the student movement persists is impossible to say, but the chant will certainly be heard throughout 2024 and beyond. It is already doing far more damage than Smith recognizes. It has the power to poison some minds and terrorize or alienate others. The chants are first of all psychological and political recruitment mechanisms, giving both established and potential antizionist students the false satisfaction of false knowledge.

They also create an illusory substitute for political analysis, an exchange of passion for knowledge that should trouble the faculty. As Donna Robinson Divine reminds us straightforwardly, “Remaking Palestine ‘from the river to the sea’ is not an achievable political aim.” It convinces students that “they are fighting for pure and sacred goals.” But it also prevents them “from acknowledging that what is promised in the struggle can never be attained.” [10]

What neither Smith nor, for that matter, the ACLU fully grasp as well is the psychological and political impact these chants have on Jewish students, especially at non-Christian institutions where the majority of Zionists are Jewish. Zionism is at the core of their identity. The mass chants are a collective assault not only on their political beliefs but on who they are. They are death chants. The ACLU’s April 26 statement about the protests implicitly leaves us with only the traditional liberal recourse: combat bad speech with good speech. But there is no speech that can ameliorate the effect of a slogan like “Glory to our martyrs” that celebrates the Hamas pogrom. Students confronted by a collective psychological assault from their peers are not merely alienated. To be surrounded by the sound of mass hatred is not merely to be made uncomfortable. Jewish students, faculty, and staff do not simply find this “deeply offensive,” as the ACLU would have it; they find it fundamentally threatening, cancelling. And that is why the ACLU’s reassuring distinction between unacceptable, individually targeted hatred and absolutely protected collective hatred is not only inadequate and unresponsive but also historically ignorant. When Charlottesville Nazi protestors chanted “The Jews will not replace us” it was not merely an idea to be discredited. It was a call for the elimination of the Jewish enemy within. I would not ask for eliminationist language to be prohibited. But I would ask universities to respond to these chants in a way that recognizes their actual destructive power. That means not only rapid denunciation but also long-term educational projects to counter their corrosive and persuasive effects.

Faced with arrests in May, the UCLA encampment chanted “HOLD THE LINE! Free Free Free Palestine.” They issued a hallucinatory press release declaring “The university would rather see us dead than divest,” with the core claim in bold. Eve Barlow describes “Enormous crowds of mentally compromised students who think they are now the Palestinians of Gaza.”[11] More than that: in an intersectional frenzy, they imagine themselves to be the vanguard of world liberation. A sign read “From Palestine to Mexico, all the walls got to go."

This reflects also reflects the purported “idealism” of some of the Hamas supporters who have occupied American campuses. They simultaneously champion and oppose mass murder. It can be assumed that few if any understand this contradiction, or understand that a Jewish exception for violence cannot be easily limited to the Jewish homeland. The only available theory to rationalize this contradiction is the conspiratorial theory of Jewish malice that animated National Socialism in Germany. It evokes the Judenrein utopia the Nazis promoted.

The problem is not whether there are idealistic and utopian participants in the occupations, along with ill-informed and naïve ones and vampires seeking blood who dream of joining Hamas on 10/7. The problem is that the idealistic participants have ceded their political efficacy to those consumed with blood lust. I do not mean that they do so willingly. That’s the risk in group action. The provocative chants and posters win the day. If there are any students who want to press for a two-state solution, they are not in evidence because they cannot make their voices heard. The chants, the posters, and the antizionist harangues are the face of the occupations. As Rich writes, they manifest “the contradiction of people claiming to want peace when they are chanting for intifada and resistance, neither of which, in this context are very peaceful.” The need for a counter-educational agenda to address this irrational conflation of mass violence and enlightenment values could hardly be greater. It is not the only challenge higher education faces, but it is a central one. It will require a large collective commitment to a long-term educational project.

People who participate in mass actions should realize that their internal personal reservations and qualifications are politically irrelevant. The people acting at the forefront of the action represent the group as a whole, whether everyone likes that or not. Of course there are wide differences of knowledge, understanding, and intent among the students and faculty participating in the occupations. But if those differences remain unexpressed or subject to marginalization or erasure, they have no purchase on events. Everyone needs to make a decision about whether they are comfortable with being absorbed into and represented by the group actions. Characterizations of individuals’ identities by nonparticipants are inevitably based on the group’s actions. Similarly, if you have a local SJP or its partner FJP chapter (Faculty for Justice in Palestine), its members will be identified with the national organization’s policies.

I will be happy to be proven wrong, but I believe campus environments have taken a long-term turn for the worse. Why? Here are fifteen reasons:

So what else can be done? Here are a few recommendations. I discuss them at length in my 2024 Hate Speech and Academic Freedom: The Antisemitic Assault on Basic Principles.

The overall point is that the situation is bleak but not necessarily hopeless, though if we fail to act forcefully it surely will be hopeless. We face well organized and well financed opponents. We do so as an underfinanced and fractured constituency. When the Jewish Federations of North America cancelled its investment in the faculty by largely eliminating its subsidiary Israel Action Network in 2019, it left us high and dry in our efforts to fight the BDS imperative in faculty associations.[13] The Federations could not process the news that faculty members teach their children, that antizionist faculty publications rationalize and underwrite anti-Israel beliefs everywhere. Now we face much more hostile opponents with our only weapons being ourselves. But our menu of options for action is not empty, and their potential impact is considerable. We will have to accept the fact that the universe of mutually competitive pro-Israel NGOs may not come to our aid. They apparently feel faculty are a lost cause. We must self-organize and self-fund. But if we do so we can build enough solidarity to help some of our colleagues overcome their fear of retribution and social isolation. Fear is our opponents’ greatest weapon, but it is a weapon we have the power to defeat.

[1] Rich, “Antisemitism after October 7: three surprises and one non-surprise,” Substack (May 19, 2024), https://everydayhate.substack.com/p/antisemitism-after-october-7-three

[2] Shrier, “Civil Rights and Antisemitism at Columbia University,” Wall Street Journal (May 25, 2024), http://www.wsj.com/articles/civil-rights-and-antisemitism-at-columbis-887a9746

[3] See Barbara J. Risman, “Does UIC want to outcompete the Ivies for antisemitism?” Chicago Tribune (March 27, 2024), https://www.chicagotribune.com/2024/03/27/opinion-university-of-illinois-at-chicago-hamas-israel-palestinians-antisemitism/

[4] See “From Stalin to Hamas: The Return of the Left that Doesn’t Learn? | An Interview with Mitchell Cohen,” https://fathomjournal.org/from-stalin-to-hamas-an-interview-with-mitchell-cohen/

[5] Harvard University, ”Report on Institutional Voice in the University,” https://provost.harvard.edu/sites/hwpi.harvard.edu/files/provost/files/institutional_voice_may_2024.pdf

[6] “Hamas leader says October 7 renewed dream of Palestinian state ‘from the river to the sea,’” Jewish Chronicle (January 22, 2024), https://www.thejc.com/news/israel/hamas-leader-says-october-7-renewed-dream-of-palestinian-state-from-the-river-to-the-sea-sb7q37c8

[7] Berman, “At Columbia, excuse the students, but not the faculty,” The Washington Post (April 26, 2024), https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2024/04/26/columbia-protest-students-faculty-gaza-unrest/

[8] Beinart, “The Campus Protests Aren’t Perfect. And We Need them Desperately,” The Beinart Notebook / Substack (April 28, 202), https://peterbeinart.substack.com/p/the-campus-protests-arent-perfect

[9] Smith, “Shibboleth,” The New Yorker (May 5, 2024), https://www.newyorker.com/news/essay/shibboleth-the-role-of-words-in-the-campus-protests.

[10] Divine, “7 October: The Campus ‘18th Brumaire’ Times of Israel (May 27, 2024), https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/7-october-the-campus-18thbrumaire/.

[11] Barlow, “UCLA versus LAPD,” Substack (May 2, 2024), https://evebarlow.substack.com/p/live-ucla-versus-lapd?utm_medium=email.

[12] Hillel/AEN, https://academicengagement.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/AEN-and-Hillel-Best-Practices-May-2024_final.pdf.

[13] I had been an IAN consultant until then.

__________________________

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Cary Nelson is Jubilee Professor Liberal

Arts and Sciences and Professor of English Emeritus at the University

of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He is an affiliated faculty member at

the University of Haifa and the recipient of an honorary doctorate

from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He is 2024 co-recipient of

the Campus Faculty Heroes Award from StandWithUs and Mothers

Against Campus Antisemitism. His most recent book is Hate Speech

and Academic Freedom: The Antisemitic Assault on Basic Principles

(2024). He is presently completing Zionism Confronts the Abyss: The

Impact of the October 7 Massacre in the Diaspora.