Download PDF Back to Research Paper Series

| Suggested Citation: Hagler, Aaron M. 2024. "Locating the 'Jew' in the Early Islamic Textual Tradition." ISCA Research Paper 2024-6 |

Download PDF Back to Research Paper Series

| Suggested Citation: Hagler, Aaron M. 2024. "Locating the 'Jew' in the Early Islamic Textual Tradition." ISCA Research Paper 2024-6 |

by Aaron M. Hagler

November 2024

The anti-Jewish sentiment that exists in the modern Middle East is a direct descendant of the picture of the “Jew” in the Islamic textual tradition.[1] That tradition, in turn, was heavily influenced by a more longstanding anti-Judaism that is foundational to many aspects of Western Civilization.[2] Islamic anti-Judaism is unique, but it is not utterly divorced from Christian antisemitism. In the European Christian tradition that emerged before the birth of Islam and has continued to develop to the present day, the “Jew,” to a great extent, was (or is) a shadowy figure who could be made to embody whatever negative stereotype a person wished to decry. This fungibility of the Jew as a category of person first found full expression in the body of second- century and later theological literature known as Adversus Judaeos, or “Against the Jews.” The goal of this body of literature was not necessarily to denigrate Jews per se (although that denigration is among its accomplishments), but rather to accomplish the necessary goal of Christian theological self-definition. In the 1st-4th century theological genre known as Adversus Judaeos literature, the distinguishing of Christianity from its Jewish roots was a paramount goal. In this environment, these Christian texts turned “the Jews” into “a nation of reprobates guilty of idolatry, depravity, murdering prophets, and, of course, rejecting God’s messiah.” They were consequently rejected by God and replaced by the Christians.[3] The genre, increasingly harsh in tone over time, was influential over not only Latin Christianity but also Eastern Christianity, where writers like John Chrysostom and Eusebius of Caesaria deployed the “Jew” as a convenient trope for accusing opponents of theological misguidedness. Adversus Judaeos works thus evolved into a pervasive tool for propagating anti-Jewish sentiment as a means of reinforcing Christian identity. When Church Fathers Tertullian and Marcion of Sinope engaged in a heated second-century debate over the proper role of Jewish scripture in Christian theology, they both accused each other of being too Jewish: to Marcion, Tertullian inappropriately revered the Jewish version of God, and to Tertullian, Marcion inappropriately read Jewish scripture literally. “Jews and Judaism thus emerged as a theological category negotiated by polemicists when laying out the contours of one sort of Christianity over and against another. ‘Jewish’ became the mud slung back and forth.”[4] Thus, in both the Eastern and Western Christian tradition, Jews became Christian strawmen, irrespective of what any individual Jews were doing or saying. This demonization not of actual Jews but of the notion of “the Jew” in the realm of Christian theology laid the groundwork for persistent antisemitism in Christendom throughout the European Middle Ages. It was, to some extent, a natural consequence of the close and contentious relationship between post-Second Temple Judaism and nascent Christianity as they emerged in conversation with each other.

The relationship between Judaism and Islam, at the time of the dawn of Islam, is only somewhat analogous to the relationship between Jews and Christianity at the time of what is colloquially named “the parting of the ways,” when Christianity first established itself as a separate community from that of Israel. Islam emerged out of the same monotheistic context that had first found expression in Judaism, but there is a key difference. Christianity derived from a local Judaean faith-based movement for communal reform, exclusively from within the Jewish traditions. Islam, conversely, emerged into a predominantly pagan Arabian world, heavily influenced by complex and contentious forms of Christianity and Judaism. Furthermore, when the early Muslims conquered territory outside of Arabia, the intercultural conversation that occurred among the Muslim Arabs, the Persians, and the mostly Greek-speaking Christians of the formerly Byzantine territories in the Levant[5] was grounded in an imperial milieu rather than a local one. Christianity had evolved from a local Jewish reformist movement to a universal imperial religion in Rome. It continued in increasingly diverse forms in the Roman-Byzantine east through the time of the Arab-Muslim conquest, while Judaism remained confined to ethnic Jews (converts notwithstanding). Thus, where Rabbinic Judaism and early Christianity developed in complementary, contemporaneous contention, the early Muslim conquerors of the Levant found a dominant, imperial set of various Byzantine Christianities including Monophysites, Diophysites, Miaphysites, Nestorians, and others.[6] The Muslims, however, were not particularly interested in the fierce theological disputes; instead, they perceived an imperial Christianity apparently in its theological feud with the Jews. Muslim scholars and theologians, eager to demonstrate the superiority of their spiritual claims, joined in kind.

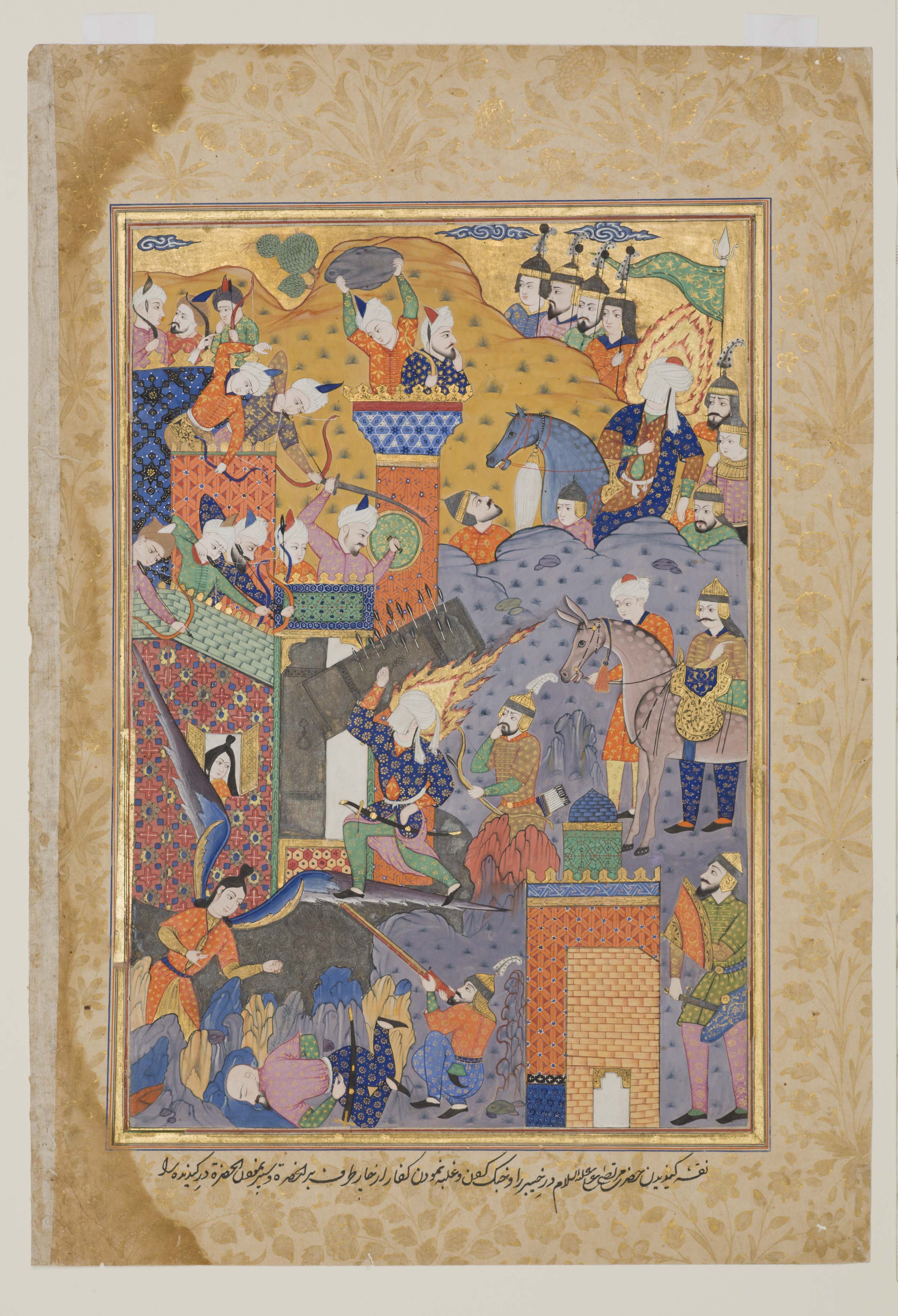

Muslims viewed Christianity’s trinitarian theology as, at best, polytheism-adjacent. Among other venues, the Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Mālik had several Qurʾānic verses mocking the notion of the trinity inscribed on the side of the Dome of the Rock.[7] Christians were far more numerous than Jews in the lands the Muslims conquered, and so by the time the Dome of the Rock was being constructed about half a century after the conquest, it was Christians rather than Jews who were the Muslims’ main theological (and still, often, political and military) adversaries in the Middle East. Jews, however, had played a bigger role in the early Islamic narrative during the life of the Prophet Muḥammad, in the Arabian Peninsula. The information we have about the interactions between the early Muslims and the Jews of Arabia include the ḥadīth, the collection of sayings and actions attributed to the Prophet Muḥammad, and the sīrat, the biographies of the Prophet, the earliest of which is al-Sīra al-nabawiyya by Ibn Hishām (d. 833 CE), based on an earlier text by Ibn Isḥāq (d. 768 CE).

According to these texts, early relations between Muslims and Jews were apparently contentious. Three Jewish tribes in Medina had been foils for the nascent Muslim community of the city following the Prophet’s emigration to it. Following the Battles of Badr (624 CE) and Uḥud (625 CE) one tribe, the Banū Qaynuqāʿ, was exiled but allowed to keep its possessions. A second, the Banū al-Naḍīr, was exiled following the confiscation of its goods. A third, the Banū Qurayẓa, was accused of aiding the Prophet’s enemies from Mecca at the 627 CE “Battle of the Trench” and, while accounts do vary, they mostly corroborate the general outlines of the tribe’s fate: a good number of the adult males—according to Ibn Isḥāq, between 600 and 900 of them— were executed, and the women and children enslaved. Still another ostensibly Jewish community, at the Oasis of Khaybār, had been subjugated by the Prophet. These Jews are remembered in the Islamic tradition as deceitful and deserving of their fates.

Most scholars accept that the Qurʾān is from the time and place Islamic tradition claims it to be, although there are some notable contradictory assertions, mostly roundly rejected (in some cases, by their own erstwhile proponents).[8] Even if we can ignore “the resistance to the application of historical-critical methodolog[ies] to the Islamic holy book [that] characterizes much of contemporary Qurʾānic studies”[9] that causes scholars to accept the traditional Islamic claims of its era, we cannot ignore the fact that much of the Muslims’ own understandings of it, in the form of the exegetical commentary of the tafsīr and the biographies of the Prophet, known collectively as the sīrat, come at best more than a century after the fact. Thus, the words of the Qurʾān may indeed be early 7th century CE words, but the textual body of Islamic scholarship that clarifies their meaning and intent is subject to the same historiographical forces that color our understanding of all historical texts, sacred or otherwise. In the Islamic case, “the problem with the sources,” the long gap between the earliest events in Islamic history and their demonstrable appearance in surviving texts, means that the history, exegesis, and memory of 7th century Islam is indelibly colored by the course and concerns of 8th and early 9th century Islam. Thus, all the sources and perspectives that predate the earliest surviving written records are both at least a hundred years out of date and fragmentary.

The fragmentary and asynchronous nature of the sources probably obscures a great deal of theological evolution within Islam. Rather than accept the notion that a “fully formed” Islam was born in the seventh century CE, it is more logical to see the development of Islam into the complex, nuanced, and vigorous collection of traditions that it was when it came into historical focus around the middle of the 9th century CE as a gradual process. This process allows us to see Islam, like Christianity before it and like the Druze and Bahāʾī faiths after it, as having sprouted from earlier monotheistic traditions and evolved into itself through conversation and polemic with and against Christianity and Judaism, and against the pagans in the same neighborhood, and through internal debates and discussions among its own intelligentsia.[10] The Qurʾān explicitly acknowledges both Judaism and Christianity as genuine, divinely-inspired monotheisms which had gone astray. It is perfectly reasonable, therefore, to assume that in its full expression, Islam’s textual tradition is, like the Christian Church Fathers writing Adversus Judaeos literature, in part a conversation with earlier monotheisms, undertaken in an attempt to self-identify and to distinguish itself from them.

What did the early Islamic textual tradition make of the Jews? And just who were these Jews who are remembered by the Islamic textual tradition?

The Qurʿān’s perspective on the Jews is best described as deeply ambivalent. As Bar Asher describes it, the Qurʿān

recounts many well-known biblical episodes in close detail, some of them more than once. These include: the history of the Patriarchs; the servitude of the children of Israel in the land of Pharaoh; their departure from Egypt; their arrival and settling of the Holy Land; and the giving of the Torah. One also finds references to various miracles that occurred to the children of Israel during their time in the desert: the pillar of cloud that accompanied them; the manna from heaven; the quail that fell from the sky; and the water that sprang forth from a rock to slake the people’s thirst.

“The biblical figures whose stories are mentioned several times include those of Abraham and his family; Lot and his kin; Moses and the children of Israel’s suffering in Egypt; and, in passing, the story of the scouts sent by Moses before entering the Promised Land; David and Solomon, Jonah (Yunus), also called Dhu l-nun (the man of the fish), Job (Ayyub), and many others.[11]

At the same time,

the Qurʿan casts doubt on the authenticity of the Jewish Scriptures of its time and accuses the Jews of having falsified them, with the particular motive of suppressing or modifying passages that allegedly heralded the coming of Muhammad and Islam, as well as their triumph and superiority over all earlier religions, Judaism included….[and while it] takes abundant inspiration from Jewish halakha, both in terms of its general concepts and in matters of detail….Islamic tradition has throughout its history exhibited a desire to sharply distinguish itself from Jewish practices….to underscore the independent nature of Islam as a religion, thus obviating any need to reference the religions that preceded it.[12]

In summary, the Banū Isrāʾīl—the “children of Israel”—are depicted as “a chosen people (Q. 2:47 and Q.2:122) whom God freed from servitude by leading them out of Egypt and into the Holy Land (Q. 5:21)”[13] but also as polytheistic backsliders (Q. 5:13) and killers of Prophets. Truly, the Qurʾānic “children of Israel” carries a mixed record of religious accomplishment; the designation “Jews,” yahūd, conversely, generally refer to Muḥammad’s contemporaries, and as such are much more negative.

Functionally, the Qurʾān’s Jews (yahūd) and Banū Isrāʾīl frequently served as negative examples, with the “positive” notices providing a basis for a wider point about ingratitude or disloyalty. 45:16 notes that “in the past We [i.e., God] gave the Children of Israel the Scripture and the Judgment and the Prophethood and We provided them with good things and preferred them over all created beings.” 2:47 directly addresses them: “Children of Israel, remember my blessings which I bestowed upon you and how I favored you over [all] created beings,” and then goes on to mention “the exodus from Egypt, the crossing of the Red Sea with dry feet, and Pharaoh’s drowning….alongside…the manna and quails that fell from the sky and the twelve springs that appeared when the people complained to Moses of the lack of water.”[14] These reminders are punctuated by other verses that castigate the Jews, implying that their election could be stripped and given to others. 5:18 states “The Jews and the Christians say: ‘We are the children of God, the ones He loves.’ Say: “Then why does he punish you for your sins?’ No. You are mortals, of those He has created. He forgives those whom He wishes and punishes those whom He wishes. God has sovereignty over the heavens and the earth and that which is between them. To Him is the journeying.” In other words, the Jews were chosen—but that choice could be revoked for bad behavior. The Qurʿān makes the case that Jewish misdeeds, which it recounts, were sufficient for this revocation of divine favor to occur.

Jews are presented as rebellious breakers of the Covenant (sūra 8), which may well be a topical reference to the Jews of Medina, who will be discussed shortly. Their backsliding into the polytheistic worship of the Golden Calf is probably their worst offense (sūra 20), which “serves to underscore the Hebrews’ idolatry and to call into question their commitment to monotheism.”[15] According to the Qurʾān, the Torah predicted the life and prophethood of Muḥammad, but the Qurʾān “accuses the Jews of tendentiously falsifying (taḥrif) the [Torah] and modifying (tabdil) the order of its verses” (sūra 2 and sūra 4, among others).[16] The Qurʾān also seeks to establish that the Jews were killers of Prophets (sūra 2 and sūra 5), although the identities of the slain prophets are never revealed. Various guesses for the kernel of this idea include the crucifixion of Jesus, the killing of Zechariah (the father of John the Baptist), or the biblical verses (1 Kings 19:10 and Jeremiah 2:30 from the Tanakh; Matthew 23:37, Luke 13:34, Romans 11:3; and I Thessalonians 2:14-15 from the New Testament) that refer to the deaths of prophets in evocative and metaphorical language.

That the Qurʿān would spend so much time on the Jews, Jewish history, and Jewish misdeeds is understandable in the context of the revealed text’s mission: to establish the Prophet Muḥammad as the last of the Monotheistic Prophets in a line that extends back to the Jewish Torah, and to advocate for the Qurʿān’s place as the final chance for humanity to come into accord with God’s will. This revelation would make the Torah and the New Testament obsolete: it would, to use the legal Islamic term, abrogate them. The notion of naskh (abrogation) is derived from the Qurʾān itself: “Such of Our revelations as We abrogate or cause to be forgotten, We bring in their place better or similar ones. Do you not know that God is capable of all things?” (Q. 2:106). Thus, some verses in the Qurʾān abrogate others; similarly, the Qurʾān and Islam abrogate the Torah and Judaism and the New Testament and Christianity. Presumably, had the Jews been more grateful to God for the blessings he had bestowed upon them, perhaps a new revelation (or two) would not have been necessary. In fact, the rebelliousness, unruliness, and ingratitude of the Jews were both necessary preconditions to God’s decision to reveal the Qurʾān and useful object lessons on crime and punishment for the believers.

However, there is a matter of genuine confusion regarding just who these “Jews” may have been, one which we will take up shortly. Verse 9:30 of the Qurʾān states: “The Jews say that ʿUzayr is the son of God and the Christians say that al-Masīḥ is the son of God. That is what their mouths say, conforming to what was said by those who disbelieved before them. May God confound them! How they have turned away!” These negative references to Jews appear to be a baffling misrepresentation of a central, defining aspect of Rabbinic Judaism, as it developed in conversation with Christianity: the categorical rejection of divine offspring.

Who were these Jews who so angered God?

The standard Islamic historical narrative of the Prophet Muḥammad’s interactions with the yahūd (Jews) of the city of Medina presents methodological difficulties. Because the earliest surviving attestation of this story is from close to two centuries after the fact (and with intervening events that almost certainly colored the story, including the division of the Muslim community into the increasingly distinct Sunnī and Shīʿī sects and two remembered changes in dynasty), when we discuss these events we are discussing the later narrative of them rather than the history as it actually happened. It is important, therefore, to remember that the narrative of events described by the Arabic Muslim sources cannot be understood as a description of actual historical events but must rather be treated as a ninth-century story that was the end result of a likely editorial process, utterly hidden from our present view, of both natural evolution and purposeful change. The biography of the Prophet Muḥammad, al-Sīra al-nabawiyya, written by Ibn Hishām, a later rendition of Sīrat rasūl Allāh by Ibn Isḥāq, is a useful source, although only confirmable to close to two centuries after the Prophet’s death. It is, nonetheless, the earliest still-extant version of the Prophet’s biography. While it therefore does not provide a reliable picture of the Prophet’s life and times,[17] it certainly provides a useful snapshot of what some ninth century Muslims thought about their seventh century Prophet. While this is admittedly an oversimplification, generally speaking the Sīra takes into account and streamlines the depiction of the Jews from those textual traditions.

In the Sīra, the Prophet Muḥammad encountered many Jews. Rarely are the stories complimentary. After a brief discussion of the holy men, including Jewish rabbis who “had spoken about the apostle of God before his mission when his time drew near,”[18] which when viewed against other references to Jews in the work is clearly designed to set up later Jewish perfidy, the Sīra has sections with titles like “The Jewish Warning about the Apostle of God.”[19] Then, after the Prophet’s emigration to Medina, there are sections called “The Names of the Jewish Adversaries,”[20] “The Jews are Joined by Anṣārī Hypocrites,”[21] “The Rabbis who Accepted Islam Hypocritically,”[22] and “References to the Hypocrites and the Jews in Sūrat al- Baqara [“the Cow”].”[23] The “Jewish Adversaries” are pilloried for “annoy[ing] the apostle [Muḥammad] with questions and introduc[ing] confusion, so as to confound the truth with falsity.”[24] The story does praise a couple of Jews by name: ʿAbd Allāh ibn Salām for accepting Islam, and when he does so he asks the Prophet for protection with the words “the Jews are a nation of liars and wish you would take me into one of your houses and hide me from them,” and Mukhayriq, a “learned Rabbi owning much property in date palms,” who willed his property to the Prophet Muḥammad.[25] Jews are further castigated for “assembl[ing] in the mosque and listen[ing] to the stories of the Muslims and laugh[ing] and scoff[ing] at their religion.”[26]

From this inauspicious start, matters progressed to the tale of the three Jewish tribes who ran afoul of the Prophet’s leadership in Medina already described. The story of the expulsion of the Banū al-Nadīr, the second of the two tribes to be expelled from Medina, concludes with a poem, rife with descriptors about the Jews:

“The rabbis were disgraced through their treachery,

Thus time’s wheel turns round.

They had denied the mighty Lord

Whose command is great.

They had been given knowledge and understanding

And a warner from God came to them,

A truthful warner who brought a book

With plain and luminous verses….

He said ‘(I offer) Peace, woe to you,’ but they refused

And lies and deceit were their allies.

They tasted the results of their deeds in misery,

Every three of them shared one camel.

They were driven out and made for Qaynuqāʿ,

Their palms and houses were abandoned.”[27]

In this story, the deportation of the Banū al-Nadīr was followed by the assault on the Banū Qurayẓa, the execution of most of its men, the enslavement of most of its women and children, and the plundering of its property. The Banū al-Nadīr, too, did not escape destruction for long; the Prophet used a period of ceasefire in his war with Mecca to attack, subdue, plunder the lands of, and ultimately destroy the Jewish community of the oasis of Khaybār, to which the Nadīr had previously fled.

When Ibn Hishām composed his version of the Prophet’s biography in the early 9th century CE, he presented the Jews of the Prophet’s time with the same communal characteristics and (lack of) values as the Qurʾān’s Jews: challengers, deniers, fighters, and occasionally killers of Prophets; doubters, questioners, and mischief makers who sew the seeds of doubt with their lies, obfuscations, and stubborn rejections of obvious truths; and deservers of punishment inflicted both by God and by righteous men. The Qurʾān described them as such, and the Sīra provides perfect examples in the hypocrite Rabbis, the few Jews who left the fold, and the perfidious Jewish tribes of Medina.

Within Islam’s classical textual tradition, the Jews played an irredeemable role. But is it true?

The role of the Jews in the Qurʾān and Sīra is sufficiently muddled to raise some important questions, many of which were just discussed. Under the assumption that the Qurʾān is indeed an early-mid seventh century text and the other genres of sacred and sacred-adjacent material reflect the perspectives of the early ninth century at the earliest, one plausible, though admittedly speculative, possibility is that the much more solid negative image of the Jew of the later texts reflects an attempt to exegetically account for what seem, to nonbelievers at least, as the apparent errors of the ostensibly infallible Qurʾān. To understand these requires an argument grounded in a nuanced understanding of Arabic grammar, syntax, morphology, and orthography.

The Qurʾān’s claim about ʿUzayr is perhaps the most prominent piece of evidence that the Jews with which Muḥammad had contact were not practicing traditions within the mainstream of Judaism. Not only is the notion of a “son of God” anathema to Judaism as we know it today, but it also lacks any attestation in any Jewish source in history, before or after, that is not a direct response to this specific Qurʾānic claim.[28] The figure of ʿUzayr, too, is a murky one when viewed from the Jewish perspective. Who is this ʿUzayr? A number of suggestions have been made, including that it is “a deformation of the biblical word ʿAzazel (Leviticus 16:8- 10, which probably refers to a demon,” or, possibly, an Arabic rendering of the Egyptian god Osiris).[29] Another suggestion identifies ʿUzayr with Enoch.[30] But by far the most common understanding of ʿUzayr is that it refers to Ezra the Scribe (proponents of the Enoch hypothesis identify Ezra as “an avatar of Enoch”). As Bar-Asher sums it up, this vision of Ezra/ʿUzayr “is seen as one of the prophets of the people of Israel…and he is said to have played a central role in teaching the Bible to the Jewish people following their return from Babylonian exile [during which] they had lost the Torah ‘and their hearts forgot it.”[31] Credited with reviving the Torah, this Ezra receives praise but also some scorn: Ibn Ḥazm (d. 1064), a leading Andālūsī (Spanish) historian, jurist, and theologian, eventually accused ʿUzayr of being the falsifier of the text rather than its reviver.

The identification of ʿUzayr with any of these figures strains credibility, for a variety of reasons, including the way some Arabic letters resemble each other. For example, the identification with the demon ʿAzazel requires a mistranscription to have occurred.32 Of course, the notion that Jews actually worshipped a demon as the son of God is unattested elsewhere, and, given the Qurʾān’s many castigations of the Jews as a calf-worshipping, text-falsifying, disobedient, unruly, and unworthy chosen community, one would assume that their worshipping of a demon would receive far more Qurʾānic attention than it does. A difference in pronunciation rather than a typographical error could get us to ʿUzayr from the Arabic word for Osiris.[33] This is also highly unlikely, for both theological and social reasons. While perhaps not as wicked as the worship of a demon, a Jewish turn away from God towards polytheism would make impossible the inclusion of Jews as ahl al-kitāb (“people of the book”) and protected dhimmīs (monotheists immune from forced conversion, whose erroneous religion must be tolerated). As for the Ezra hypothesis, there is, indeed, a grammatical relationship between the names Ezra and ʿUzayr in Arabic: ʿUzayr would be the diminutive “nickname” form of ʿAzrā, much in the same way that the diminutive form of kalb, “dog,” is kulayb, “puppy.” This would mean that the translation of ʿUzayr, if we may briefly shift into a Yiddish mindset, might better be rendered as “Ezraleh.” It is possible, but again, the absence of any Jewish text corroborating this notion of Ezra as the son of God, and what one imagines was the befuddlement of Jewish theologians when challenged on this point by their Muslim counterparts, made the inclusion ʿUzayr awkward for Muslims who asserted the Qurān’s infallibility.

Interestingly, none of the Muslim guesses at the identity of ʿUzayr focus on his role rather than his name. The notion of a “son of God” is a Christian notion, or at the very least had become one by the time of Islam; and the verse in the Qurʾān, 9:30, that asserts that “the Jews say ‘ʿUzayr is the son of God’” immediately follows it with “and the Christians say ‘al-Masīḥ [Christ] is the son of God.” The verse concludes: “That is what their mouths say, conforming to what was said by those who disbelieved before them. May God confound them! How they have turned away!” So even as we confront a profound mystery about the Qurʾān’s understanding of Jewish theology, there is no confusion about Christian theology, although the verse is critical of it.

The Qurʾān is frequently poetic, and the use of Jesus’s cosmic role—al-Masīḥ, a direct cognate to Messiah—rather than his name,ʿĪsā, which appears directly twenty-five times in the Qurʾān, invites us to view ʿUzayr in parallel grammatical construction as a title or role rather than a proper name. The Hebrew word ozer, meaning “helper,” is a far better homonym to ʿUzayr than is either ʿAzāzīl or ʿŪzūris;and, beyond being a better fit in terms of the verse’s poetry, as an active participle it has at least the potential to be a Hebrew title similar in function to al-Masīḥ: Psalm 33, for example, asserts that “Our soul waits for God: he is our help (ezrenu, from ozer) and our shield.” This is just one possibility, of course; Ozer is not attested as a Jewish “son of God” either. It simply makes better poetic, grammatical, conceptual, and auditory sense than the other candidates.

Islamic commentary on the verse was forced to confront the ʿUzayr problem. “Some exegetes limited the scope of the accusation, holding that it was directed against a belief from the distant past and remarking that no similar blasphemy was to be found among the Jews of their time. Others maintained that this idea was never held by more than a small group of Jews. According to others, a single Jew exhibited this belief, a certain Finḥas.”[34] The ascription of such a profoundly Christian notion to Jews tempts us with the notion that the Jews Muḥammad knew were not, in fact, mainstream Jews at all.

Beyond the question of ʿUzayr’s identity, Patricia Crone points out several other compelling pieces of circumstantial evidence that the “Jews” in the Qurʾān were adherents of a kind of Christianity (she calls it “Jewish Christianity,” a notion that comfortably aligns with Martin Goodman’s visualizations of the Christian/Jewish “parting of the ways”[35]). She writes that, in the Qurʾān, there are “four points [that] are extremely hard to explain without recourse to the hypothesis of a Jewish Christian contribution [to the Qurʾān]: the Qurʿānic Jesus is a prophet sent to the Israelites, not the gentiles; the Israelites appear to include Christians; the [Prophet Muḥammad] sees Jesus as second in importance to Moses and as charged with a confirmation of the Torah; and insists that Jesus was only a human being, not the son of God.”[36] Still other apparently Jewish Christian notions that appear in the Qurʿān include the notion that Mary was a descendant of Aaron and that Jesus was born under a palm tree instead of in a manger.[37] All told, she notes “a full seven doctrines, several of them central to the Qurʾān, [that point] to the presence of Jewish Christians in the [Prophet’s] locality.”[38] Furthermore, “since [Jewish Christians] are attested in Egypt in the seventh century, there is nothing particularly hazardous about postulating that they were present in Arabia too.”[39] This assertion of Crone’s parallels earlier attempts to identify the Jews of Muḥammad’s milieu, such as those of Goitein, who assumed they were “ordinary Talmudic Jews” who had “come under the influence of [Christian] monastic piety and adopted some of its practices and possibly also some of its literature.”[40] Aswe would understand it today, the Arabian Jews of Muḥammad’s time were most likely not Rabbinic, Talmudic Jews, but Jews who remained in the strange gray zone between Judaism and Christianity: ethnic Jews who accepted Jesus as a Messiah (this is just a hypothesis, but perhaps they even termed him ozer, “helper”), but who had perhaps not joined “mainstream” Christianity in their acceptance of the globalization of his prophetic mission.

As unlikely as this may sound, at least one contemporaneous Jewish text lends it credence: the Secrets of Rabbi Shimʿon bar Yoḥai, an apocalyptic text dated from perhaps the middle of the eighth century, whose “predictions” include the rise of the Arab Muslim empire. According to this text, while Rabbi Shimon was hiding in a cave from the wrath of the Byzantine Caesar, he received a vision. The text recounts: “When he understood that the kingdom of Ishmael [i.e., the Arabs] would come upon [Israel], he began to say ‘Is it not enough, what the wicked kingdom of Edom [i.e., Rome/Byzantium] has done to us that [we must also endure] the kingdom of Ishmael?” And immediately Metatron the prince of the Presence answered him and said: ‘Do not be afraid, mortal, for the Holy One, blessed be He, is bringing about the kingdom of Ishmael only for the purpose of delivering you from that wicked [Rome]. He shall raise up over them a prophet in accordance with His will, and he will subdue the land for them; and they shall come and restore it with grandeur.”[41] The exceptionally positive presentation of the Prophet Muḥammad and his followers is as perplexing as the appearance of ʿUzayr in the Qurʾān, if we take the Sīra’s account of the destruction of the Jewish community of Medina at face value. By the time the Secrets was composed, the Muslims had conquered the entire Middle East, and had the confrontation between the Prophets and the Jews of Medina resulted in a pogrom, as the Muslim sources assert, one would expect the Jewish sources to have a much less positive take on the Prophet’s community. Not all Jewish sources at the time were so positive, of course, but it is striking that not a single one of them accuses Muḥammad of ethnically cleansing Medina of its Jews.

When we look at the twin mysteries of ʿUzayr and the Secrets of Rabbin Shimʿon and try to align them with the historical narrative, three distinct possibilities emerge. The first is that the Jews of Medina were ignorant of their own religion’s mainstream theology, and that they really did claim that ʿUzayr was the son of God, and also that Jews a mere century later ignored an attack against their cousins in Medina. Inasmuch as this is the most accepted narrative, the notion that the Qurʾān would be so wrong about Jewish theology and that the author of the “Secrets” would be so forgiving seems unlikely. A second possibility is that the Jews the Prophet Muḥammad encountered were not, in fact, mainstream Jews. In this case, ʿUzayr would be a Messianic title used by a community of Jewish Christians. Since the “Jews” of Medina were actually Christian or adjacent, according to the Jewish understanding of them, Jews elsewhere in the Middle East did not register their erasure as an anti-Jewish attack. This would comfortably explain why the Secrets would discuss the Prophet Muḥammad with such optimism. This explanation is possible, but it seems like such an easy explanation that one would expect the Muslim scholars—who quickly became learned in the spiritual disputations of their conquered populations—grappling with the ʿUzayr problem to have asserted it once they discovered it. The third possibility is that the story of the Jews of Medina was a fiction (after all, its first appearance in surviving textual form is not until some years after the accepted date of the composition of the Secrets), designed to present the actions of Jews as consistent with their characteristics as they are presented in the Qurʾān. Nothing is conclusive, but this possibility is the most likely of the three. While the Qurʾān may well have been confused about ʿUzayr, the notion that no pogrom against Medinan Jews ever occurred is far more comprehensive an explanation for the episode’s absence in non-Muslim sources than is the notion that the victims were Christians.

Taken individually, the curious case of ʿUzayr and the underhandedness and obstinance of the Qurʾān’s Jews, the absence of corroborating evidence for the destruction of Medina’s Jewish community, and the bizarrely positive perspective of Muḥammad that we find in the Jewish apocalyptic text, the Secrets of Rabbi Shimʿon bar Yoḥai raise eyebrows. The historiographical challenge presented by the dearth of sources demonstrably contemporaneous with the life of the Prophet and that dearth’s implications for the stories of his life provide a fertile context for placing these three disorienting clues to the past in conversation with each other. When viewed as triangulating vertices, a discernible picture emerges, either of Jewish Christians with novel terminology for the Messiah standing in for “Jews,” or of an entirely invented episode designed to corroborate the Qurʾānic role of the “Jews.” If the episode involving the three Jewish tribes was indeed invented, then the Jews of Medina have far more in common with William Shakespeare’s Shylock than with any historical persons: they were characters constructed to embody prevailing stereotypes, whose actions and identities serve as mirrors for the cultural and theological biases of their creators. The Islamic variety of antisemitism deploys the “Jews” as prophet-fighting, God-opposing, underhanded villains. In the end, the “Jew” is precisely what the tradition needed him to be: an adversary. Prevailing antisemitic notions may be based on a misapplication of the name “Jew” or on a fiction created for the purpose of substantiating a Qurʾānic misunderstanding of Jewish and Christian theology. On the other hand, early antisemitic Christian notions of the “Jew” were also based on fictions, in that case deployed in the service of Christian theological self-definition. Thus, it would seem that, for all their seeming differences, Islamic and Christian antisemitism were cut from the same self-serving fabric.

On August 18, 1937, with anxiety about Jewish immigration to Palestine on the rise, a pamphlet entitled “Islam and Jewry” was published in Cairo. Promoting the Prophet Muḥammad’s struggles against various Jews in his life from minor episodes to central themes, the text asserts that the struggle “between the Jews and Islam began when Muhammad fled from Mecca to Medina….At that time the Jewish methods were already the same as today. Their weapon as ever was defamation….They tried to undermine Muḥammad’s honor…[asking him] senseless and unsolvable questions…..But with this method, they had no success, [so they] tried to eradicate the Muslims.”[42] Going on to emphasize the Qurʾānic verses that stigmatize Jews, and asserting their applicability to modern Jews, the pamphlet converged with prevailing European notions of antisemitism by giving the Jews “a certain unchanging nature with negative characteristics.”[43] Critically, the pamphlet was written by the Nazi propagandist Johann von Leers before being translated into Arabic.

As Nirenberg has shown, antisemitism is adaptable to a variety of environments. In the context of the present round of conflict, situating the “Jew” in the particular branch of Islamism that provides the underpinnings for Hamas’s ideology brings us to the writings of Sayyid Quṭb (died 1966), an Egyptian education scholar who studied under Hassan al-Banā, the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood. Hamas, of course, is a militant offshoot of the Egyptian Islamist organization. Quṭb was disenchanted with the West following a term of study at the Colorado State College of Education (now the University of Northern Colorado), during which he perceived Western spiritual bankruptcy and what he called a “Crusader spirit” in a series of essays entitled “The America that I Have Seen.” Quṭb was subsequently jailed for his opposition to, and possible plotting against, the socialist-leaning Egyptian government of Gemal Abdel Nasser (ultimately, he would be hanged for his role in a plot to assassinate Nasser). Quṭb’s oeuvre, including Milestones, generally considered fundamental to his Islamist thought, formulates a doctrine of governance and daily living that places Islam at the very center. His essay “Our Struggle with the Jews” is essential to understanding his historical role as the modern thinker who completed the work of bridging the classical textual tradition with modern calls to antisemitic action. While Quṭb never made explicit reference to von Leers’s pamphlet “Islam and Jewry” itself, both authors propagate the idea of a long-standing, malevolent Jewish conspiracy against Islam and Muslims.

“The Muslim community,” Quṭb begins “Our Struggle with the Jews,” “continues [even today] to suffer from the same Jewish machinations and double-dealing which discomfited the Early Muslims. But the Muslim community (today) does not—one must say with great regret— utilize those Qurʾanic directives and this Divine Guidance.”[44] Quṭb warns that the “Jews’ way of attacking through sowing doubt and suspicion in the Muslim community continues,” but with new methods: by Quṭb’s day, the Jews had confused nominally Muslim religious scholars,“weak-minded Muslims [who] teetered between belief and apostasy,”[45] to construct concepts and methods whose ultimate goals were the destruction of Islamic society. Making no distinction between “Jews” and “Zionists,” and emphasizing the “evil psychology” of the Jews in the Qurʾān, who “perpetrated the worst sort of disobedience (against Allah), [and] behaving in the most disgustingly aggressive manner and sinning in the ugliest way, [committing] unprecedented abominations,” Quṭb’s Jews are “creatures who kill, massacre, and defame prophets [from whom] one can only expect the spilling of human blood and any dirty means which would further their machinations and their evilness.”[46] Quṭb concludes his treatise: “The days continue clearly to reveal the truth of the Qurʾān in its portrayal of the nature of the nonbelievers, wherever Muslims meet them, in any time and in any place. And the most recent complications in the Holy Land, between the believers sacrificing themselves and the Jews, is a confirmation of this (Qurʾānic) teaching, in an astonishing form.”[47]

The role of Quṭb’s thought in the development of the Muslim Brotherhood, and thus the Hamas, worldview is well-studied and documented.[48] Hamas’s view of the “Jew” is the brainchild of Sayyid Quṭb; and Sayyid Quṭb’s concept of the “Jew” is explicitly cherry-picked from the early Islamic textual tradition. Hamas’s murderous and violent methods, and the presentation of Jews in their 1988 charter, are inexplicable absent the context that these are the “Jews” they think they are facing. Article 7 of that charter calls the organization “one of the links in the chain of the struggle against the Zionist invaders,” and while it makes reference to recent events and individuals, such as the 1948 and 1967 wars, the Hamas charter concludes with a ḥadīth from the canonical collections of Bukhārī and Muslim:[49] “The Day of Judgement will not come about until Muslims fight and kill the Jews, when the Jews will hide behind stones and trees. The stones and trees will say, ‘O Muslims! O Servants of God! There is a Jew behind me, come and kill him.’ Only the Gharqad tree [apparently a Jewish tree] will not do that because it is one of the trees of the Jews.” The eschatological reference to the Day of Judgment demonstrates that Hamas did not see its fight merely with “Zionists” or “Israelis,” but with Jews. Even though Hamas altered its charter in 2017 to de-emphasize its antisemitic elements, the revision still explicitly rejected the existence of the state of Israel. In any event, the antisemitism of Hamas has clearly not softened, notwithstanding the erasure of the reference to that particular ḥadīth in its charter.

Even beyond Quṭb and Hamas, the early Islamic textual presentation of the “Jew” continues to have resonance. One of the more popular chants at anti-Israel demonstrations since the 1980s has been: “Khaybār, Khaybār yā yahūd! Jaysh Muḥammad sa-yaʿūd!”[50] which means, “Khaybār, Khaybār, O Jews! The army of Muḥammad is going to return.” The reference, of course, is to the subjugation of the Jews of the Khaybār oasis, a military campaign undertaken by the Prophet Muḥammad during the period of hudna, ceasefire, with his enemies in Mecca. From the Muslim perspective, the cause of the war was the Jewish tribes’ reputed attempt to organize a coalition against the Prophet, perhaps spurred on by the arrival in Khaybār of the Banū al-Nadīr, the erstwhile tribe of Medinan Jews previously exiled from the Prophet’s city. The ceasefire terms after the campaign—half of the Jews’ goods and earnings were to be sent to the Muslims, and they would be allowed to continue living there—lasted until the reign of the second Caliph, ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb, when the Jews of Khaybār were expelled. Khaybār exists in Islamic memory as a triumphal example of the Prophet’s early victories over his enemies.

The memory of Khaybār is more than just a chant. The seventh-century battle, recorded in the ḥadīth and in a variety of histories, has also lent its name to a series of missiles used by Iran and Hezbollah. The Khaibar-1 was first used by Hezbollah in the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war. The most modern iteration of this missile, the Iranian-developed Khaibar-4 (also known as the Khorramshahr-4) was part of the Iranian strike on Israel in April, 2024. The narrative of Khaybār has become emblematic of Islamist notions of confronting, and ultimately subjugating, the “Jew.”

The antisemitism that exists in the Islamic world is multifaceted and eclectic. Some of it is simply medieval Christian antisemitism or Nazi antisemitism more or less directly translated into Arabic.[51] Arabic translations of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Mein Kampf remain popular books in the Islamic world. However, the shape of Islamic and Islamist antisemitism is heavily influenced by the memory of the Jews of the Qurʾān and of the Prophet Muḥammad’s lifetime. One of the reasons that “Islam and Jewry” was produced by the Nazi Johann von Leers is precisely because Nazi racial antisemitism did not catch on in the Islamic world, and von Leers found in the textual tradition the raw materials with which to construct a new path to hatred of the Jews in an Islamic context. The textual tradition thus plays a central role in shaping these Islamist antisemitic attitudes: by defining the “Jew” as a figure born with a predisposition to enmity with God, to ingratitude, and to rebellion, the Qurʾān lays the groundwork for text- based suspicion and fear. When combined with stories from the sīra and the reports present in canonical ḥadīth collections which portray Jews as treacherous adversaries, and when corroborated by European antisemitic tracts, this syncretic take on the tradition has ingrained negative stereotypes about Jews deeply within Islamic culture. Accusations of taḥrīf, purposeful falsification of scripture (such as the denial of Jewish regard for ʿUzayr), serve further to delegitimize Jewish religion and identity. This is why references to Khaybār and the Gharqad tree (a ḥadīth in which stones and trees, except the ostensibly “Jewish” Gharqad tree, will call out to Muslims to kill Jews hiding behind them; this ḥadīth was explicitly mentioned in the Hamas charter) seem to have such resonance, and extend the legacy of these texts into educational materials and religious sermons, where these historical narratives are used to frame contemporary issues.

It goes without saying, but must nonetheless be said, that such anti-Jewish views are not universal among the world’s Muslims. There are certainly Islamist groups today vociferously pushing anti-Jewish doctrines based on this cherry-picked piece of the textual tradition, and there are certainly some Muslims who are convinced of or sympathetic to these views who do not actively propagate them. It is impossible to estimate their numbers. Critically, there are also Muslim voices actively decrying antisemitism, in some cases emphasizing other pieces of the textual tradition like 2:62, which states “Indeed, those who believe in Islam, and those of Jewry, and the Christians, and the Sabians—whoever among them truly believes in God and in the coming judgement of the Last Day and works righteousness—shall have their reward with their Lord,” which underscores the fact that in the early and medieval Islamic world, Jews often could and did live safely, and sometimes thrived. Such groups include the Canada-based Council of Muslims Against Antisemitism. For the most part, however, such voices seem to be outside the Middle East, and in the post-October 7 and Gaza War context, it is difficult to imagine that situation changing anytime soon. Despite the presence of some Muslim voices opposing antisemitism, the unfortunate reality is that these perspectives often struggle to gain traction in religiously dogmatic segments of the population (and, to be clear, hate based on dogmatic worldviews is by no means the exclusive provenance of Muslims; it exists everywhere, including, of course, against Muslims). The prevalence of antisemitic rhetoric within those groups and the perpetuation of selective interpretations of Islamic texts, combined with the socio-political dynamics of the Middle East, suggest that substantial change is likely to be slow and arduous.

[1] While this essay primarily examines the antisemitic narratives within the classical Islamic textual tradition and their influence on modern attitudes, it is important to recognize that these views are not universally held among Muslims. Various Islamic scholars, both historical and contemporary, have interpreted the Qurʾān and other texts in ways that emphasize tolerance, coexistence, and respect for Jews and other religious communities.

[2] David Nirenberg, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2014), 1-6.

[3] Joshua Garroway, “Church Fathers and Antisemitism from the 2nd Century through Augustine (end of 450 CE),” in The Cambridge Companion to Anti-semitism, edited by Steven Katz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), 68.

[4] Ibid., 70.

[5] Greek was the language of elite Christianity, but most of the native Christian population spoke in Aramaic in Syria and Mesopotamia, Coptic in Egypt, and Armenian in Armenia, among other local colloquial dialects. Even so, while many of the Christian-to-Christian theological conversations may have required interlocutors to be bi- or even trilingual (and an engagement with all of these languages would be necessary to comprehend developing Christian theology of the seventh century CE), the vast majority of the early conversations between Christians and Muslims were between Arabs and Greeks. See Anne Bradshaw and Paul Crawford, The Pilgrimage of Egeria: A New Translation of the Itinerarium Egeriae with Introduction and Commentary (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2018), 47.3-4.

[6] This is in addition to areas outside of Roman and Byzantine control that also largely converted to Christianity, including Armenia and Georgia, as well as the Church of the East in Mesopotamia and Persia, which were part of the Sassanian Empire. For a discussion of the varieties of Christianity that came into direct contact with the Muslims and which continued to develop afterwards, see Sidney H. Griffith, The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008).

[7] For example, Qurʾān 112 (al-Ikhlās): 1-4 includes the phrase lam yalid wa-lam yūlad, wa-lam yakun lahu kfuwan ʾaḥad(un), which means, “[God] does not beget nor is He begotten, and there is none like him.”

[8] See, among many others, John E. Wansbrough, Quranic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation, London Oriental Series 31 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977) and The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of the Islamic Salvation History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978); Patricia Crone, Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987); Crone and Michael Cook, Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977); Angelika Neuwirth, et al., Studien zur Komposition der makkansichen Suren: Die literarische Form des Koran. Ein Zeugnis seiner Historizitdt? (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017).

[9] Francisco del Río Sánchez, “The Rejection of Muhammad’s Message by Jews and Christians and Its Effect on Islamic Theological Argumentation,” The Journal of the Middle East and Africa 6:1 (2015), 60.

[10] Although Judaism is remembered as the first of the monotheistic faiths, there is no reason to assume that it alone emerged from the proverbial divine blue, either. I discuss the emergence of Judaism from a set of polytheistic traditions elsewhere, in Aaron M. Hagler, Owning Disaster: Coping with Catastrophe in Abrahamic Narrative Traditions (London: Routledge, 2024), 13-16.

[11] Meir M. Bar-Asher (Ethan Rundell, trans.), Jews and the Qurʾan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), 2.

[12] Ibid., 137-8.

[13] Ibid., 28.

[14] Ibid., 32.

[15] Ibid., 44.

[16] Ibid., 50.

[17] The translator of the Sīra into English, Alfred Guillaume, curiously encourages his readers to accept the historical accuracy of the account through what amounts to an appeal to the emotional pathos of the work. See Alfred Guillaume, trans., The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Isḥāq’s Sīrat Rasū Allāh (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1955), xxiv.

[18] Ibid., 90.

[19] Ibid., 93.

[20] Ibid., 239.

[21] Ibid., 242.

[22] Ibid., 246.

[23] Ibid., 247.

[24] Ibid., 239.

[25] Ibid., 241.

[26] Ibid., 246.

[27] Ibid., 441-2.

[28] Admittedly, there are numerous references in the Torah that refer to a son of God, which would be interpreted by Christian commentators as referring to Jesus. Rabbinic commentators categorically rejected this interpretive methodology and consistently understood these usages to be metaphorical; indeed, this difference of opinion is the most theologically fundamental distinction between Judaism and Christianity. By the time the Qurʾān, and with it this verse, was revealed, this distinction was quite calcified.

[29] Bar Asher, Jews and the Quran, 44-45.

[30] G.D. Newby, A History of the Jews of Arabia: From Ancient Times to their Eclipse Under Islam (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1988).

[31] Bar-Asher, 46.

[32] The difference between ʿUzayr and ʿUzayz is almost negligible: ﻋﺰﯾﺮ is ʿUzayr; ﻋﺰﯾﺰ is ʿUzayz or ʿAziz. Notably, at the time of the Prophet, such diacritical dots were not always included in written text. While the Arabic term for ʿAzazel is the direct cognate ʿAzāzīl, the difference between an r and a z in the Arabic alphabet is just a single diacritical dot (note: the “r” sound is connoted by ر, and the “z” sound by the same letter with a dot, ز), and if the “original” name uttered by the Prophet at the time of the revelation of the sūra in question had actually been ʿUzayz or ʿUzīz, perhaps a reference to ʿAzāzīl, rather than ʿUzayr, it would have taken only the omission of a single dot above the z for the ʿUzayz to become ʿUzayr forever (vowels, too, were not written).

[33] In modern Arabic, his name is ʿŪzūrīs, but it is not difficult to imagine an alternative archaic name of ʿUzīr, ʿUzūr, or even ʿUzayr.

[34] Ibid., 46. Finḥas is also mentioned in the Sīra as a particularly truculent and challenging Jew who earns himself a punch in the face from Abū Bakr, later to be the first Caliph, for his hostility to God.

[35] See Martin Goodman, “Modeling the ‘Parting of the Ways’” in Martin Goodman, Judaism in the Roman World (Leiden: Brill, 2007), esp. p. 182.

[36] Patricia Crone, “Jewish Christianity in the Qurʾān (Part One),” in Journal of Near Eastern Studies 74,2 (2015), 228-9. Cf. Sidney H. Griffith, The Bible in Arabic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 8-15, and esp. 11, who points to the fact that the Qurʾān seems well-acquainted with Jewish traditions as evidence for the notion that Arabian Jews were in close contact with Jews elsewhere and were in the mainstream. This may well be true, but it is also true that Jewish Christians who called themselves and considered themselves Jews would also have been “fully aware of current Jewish traditions, both scriptural and Rabbinic,” which would account for “the Qurʾān’s high quotient of awareness of Jewish lore, including biblical themes and narratives, and even of the exegetical tradition.” That they seem to have believed in a named Son of God, unattested elsewhere in the mainstream Jewish traditions, is compelling evidence that they had been convinced of at least some Christian notions.

[37] Ibid., 229.

[38] Ibid., 229.

[39] Ibid., 229.

[40] S.D. Goitein, Jews and Arabs: A Concise History of their Social and Cultural Relations (Mineola, New York: Dover, 2005). This edition is an unabridged republication of the third revised edition of the work originally published in 1974 by Schocken Books, under the title Jews and Arabs: Their Contact Through the Ages. It should be noted that the question of Christian, Jewish, and Sabian influence on Islam captivated the field for much of the 19th century. In 1933, Charles Torrey concluded “the greater part of [Islam]’s essential material came directly from Israelite sources,” even while unironically noting that “it is quite fruitless to attempt to distinguish between Jewish and Christian religious teaching at the outset of Mohammed’s career on the simple ground of essential content, naming the one or the other as that which exercised the original and determining influence over him at the time when his religious ideas began to take shape. The doctrines which fill the earliest pages of the Koran: the resurrection, the judgment, heaven and hell, the heavenly book, revelation through the angel Gabriel, the merit of certain ascetic practices, and still others, were quite as characteristically Jewish as Christian.” See Charles Cutler Torrey, The Jewish Foundation of Islam (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1967), 7. Crone’s deeper look into the actual doctrines implied by the language of the Qurʾān satisfactorily solves this problem.

[41] Stephen J. Shoemaker, A Prophet has Appeared: The Rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish Eyes (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2021), 139.

[42] Matthias Küntzel, “Islamic Antisemitism: Its Genesis, Meaning, and Effects,” in Antisemitism Studies 2, no. 2 (2018).

[43] Ibid.

[44] Sayyid Quṭb, “Our Struggle with the Jews,” in The Legacy of Islamic Antisemitism, ed. Andrew G. Bostom (New York: Prometheus Books, 2008), 354.

[45] Ibid., 357.

[46] Ibid., 357.

[47] Ibid., 362.

[48] See, among others, John Calvert, Islamism: A Documentary and Reference Guide (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007); John Calvert, Sayyid Qutb and the Origins of Radical Islamism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009); Ahmad S. Moussali, Radical Islamic Fundamentalism: the Ideological and Political Discourse of Sayyid Qutb (Beirut: American University of Beirut Press, 1992); Ronald L. Nettler, Past Trials & Present Tribulations: A Muslim Fundamentalist’s View of the Jews (New York: Pergamon Press, 1987); James Toth, Sayyid Qutb: The Life and Legacy of a Radical Islamic Intellectual (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[49] Bukhārī and Muslim are the names of the compilers of two of the six ḥadīth collections widely regarded in Sunni Islam as the most authoritative sources of information relating to the sayings and actions of the Prophet Muḥammad. These collections are: Ṣaḥiḥ Bukhārī compiled by Muḥammad ibn Ismāʿīl al-Bukhārī; Ṣaḥiḥ Muslim, compiled by Muslim ibn al-Hajjāj; Sunan Abū Dawūd, compiled by Abū Dawūd al-Sijistānī; Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhi, compiled by Muḥammad ibn ʿĪsā al-Tirmidhi; Sunan al-Nasāʾī, compiled by Aḥmad ibn Shuʿayb al-Nasāʾī; and Sunan ibn Mājah, compiled by Muḥammad ibn Yazīd ibn Mājah. Each collection contains thousands of hadiths, meticulously gathered and authenticated by the respective scholars according to established methodologies.

[50] Or sawfa yaʿūd, which means the same.

[51] Norman A. Stillman, İlker Aytürk, Steven Uran and Jonathan Fine, “Anti-Judaism/Antisemitism/Anti-Zionism”, in Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, ed. Norman A. Stillman. Consulted online on 19 June 2024.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dr. Aaron (Ari) Hagler has a PhD in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations from the University of Pennsylvania (2011) and an MA in Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (2005). He is the author of two books: Owning Disaster (Routledge, 2024) and The Echoes of Fitna (Brill, 2022). Previously, he has served as Associate Professor of History at Troy University. Currently, he is a history educator at Geffen Academy at UCLA.